INTRODUCTION

‘…… In one of the best remembered trials of its kind this drugs trial was “something very novel.” So said the Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin, QC who told the jury that for the first time in Bermuda’s criminal history, video tapes of crimes alleged by the prosecution would be shown in court.’

Shortly after assuming command of the Bermuda police narcotics squad in mid-1978, I met with the squad’s four detective sergeants in order to identify the top five drug kingpins then operating on the island. Each sergeant led a team of three detectives and the idea was that each team would dedicate themselves to develop evidential intelligence and sources over a period of time with the aim of dismantling the operations of their selected kingpin.

Top of the list targeted for special attention was Vernon ‘Apples’ Martin who – despite ongoing considerable intelligence I was personally hoovering-up daily from a close source concerning Martin’s importation activities – had, in December 1977, successfully landed half-a-ton of herb on the island aboard a seagoing Jamaican fishing vessel. Throughout the remainder of 1978 on-going related conspiracy investigations ultimately led to Martin’s arrest and eventual conviction in July 1979…... [See pending article]

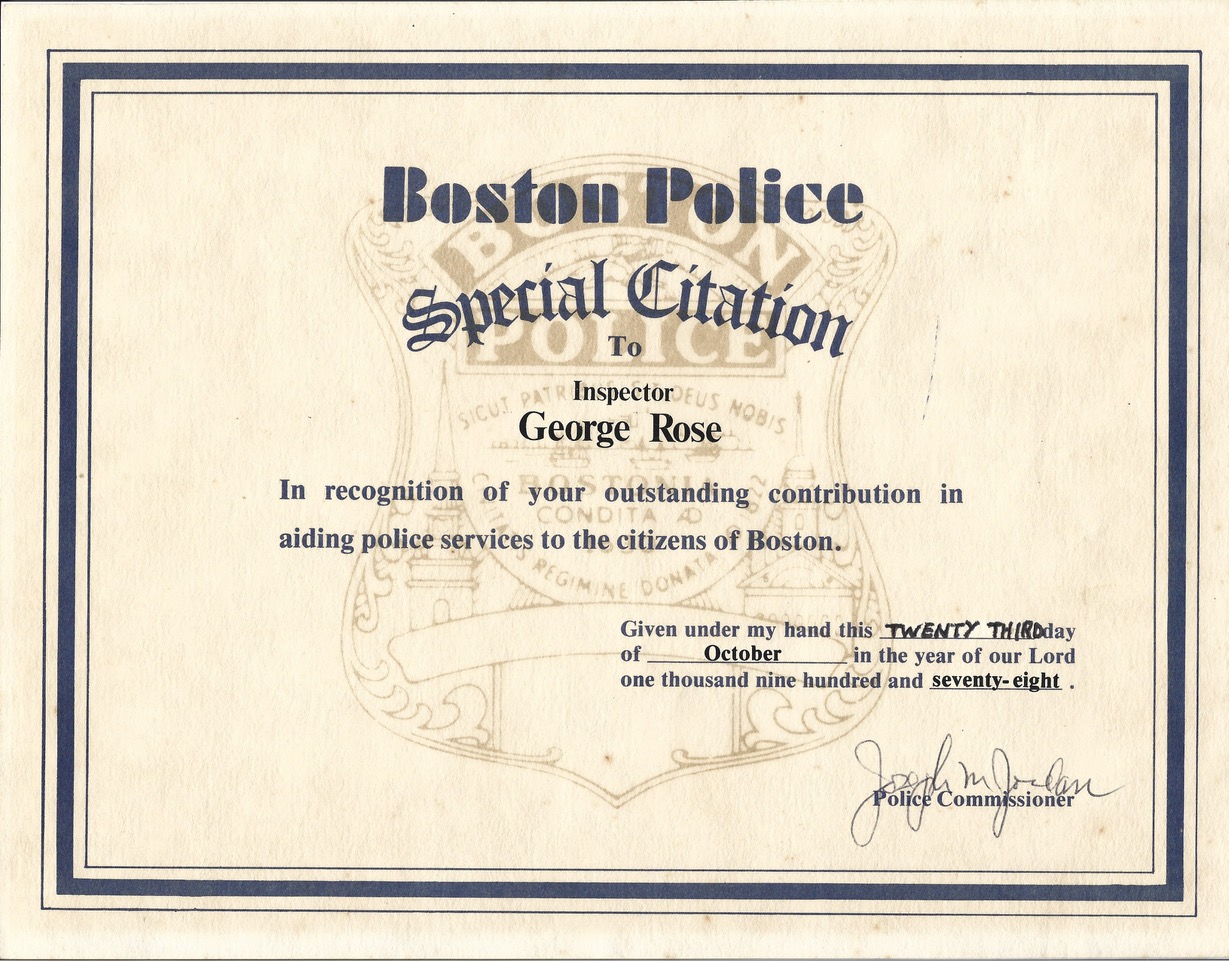

Coincidentally, in the late summer of 1978, narcotics detectives from the City of Boston Police were in Bermuda in the aftermath of a gangland massacre at the Blackfriars Pub of five men with organized crime links. Police Commissioner Joseph Jordan had commented at the time: “It was a real wicked, vicious type of crime. It was a professional hit job. It was the biggest mass murder in the history of Boston, in my memory at least.”

Here on the Island, uniform constable William ‘Billy’ Henry – then posted on Court Street patrols with a colleague, was detailed to assist the Boston officers by ‘babysitting’ a government witness to the Blackfriars slaying pending the return of the officers at the appropriate trial time in Boston. These arrangements had been made available under the newly implemented US witness protection program, and much of the witness’ ‘hiding’ time in Bermuda was spent on Court Steet as he made his rounds thereon and got to know the local peddlers who could feed him his needs.

Upon their return to the island later in the year to collect their ‘snitch’, the Boston detectives willingly provided us with practical advice and guidance on surveillance techniques of the sort required by the operation we envisaged. Constable Henry subsequently became a valued member of the Bermuda narcotics squad.

Boston police commissioner Joe Jordan later issued the following Citation to the Bermuda Police:

The video-taped crimes you are about to read concern the second kingpin on the Top Five list – Alvin Eugene ‘Chappy’ Chapman Jr.

It should be remembered that these were the days when cell phones, GPS and reliable tracking equipment as we know it today, did not exist as tools for use by law enforcement. There were no computerized software systems, land, air or sea tracking devices or equipment inventories in existence. Throughout the early 1980’s however, the only recording assets at our disposal would include the ‘loan’ of expensive camera and video equipment through the good will of a local media broadcaster who had little need for them at the time pending prolonged developments and Legislative discussions concerning the future of a proposed cablevision system on the Island.

Chapman and his cohorts were peddling a variety of drugs including heroin to a sizeable street clientele on premises located on Parson’s Road, Pembroke not far from police headquarters, Devonshire. Our efforts to take him down however were variously hindered not the least by a lack of manpower and the necessary expenses involved by the long working hours in pursuit of such an investigation.

By late 1980 Chapman’s illicit drugs marketing had expanded to such serious proportions that the matter had to be resolved as soon as possible. To this end, and in a concerted effort to gain video evidence in support of continuous intelligence then being collated from addicted street informants, intermittent surveillance on the Parson’s Road premises began on February 1, 1981.

It was hoped at this time to put Chapman finally out of business by this single strike on these premises but, as you will read, these efforts would progress in two separate stages as they became intermingled in the ensuing court processes.

1981

In early March 1981 police narcotics officers raided the two neighboring houses used by Chapman in his illicit drug trading on Parsons Road, Pembroke. Seven men were initially apprehended in the raid which lasted over two hours. Five of the seven men including Chapman had been arrested before police left the scene that day.

[Note: Neither of these two neighboring houses turned out to be the official residence of ‘Chappy’ Chapman who, it was determined, actually lived on Lighthouse Road, Southampton.]

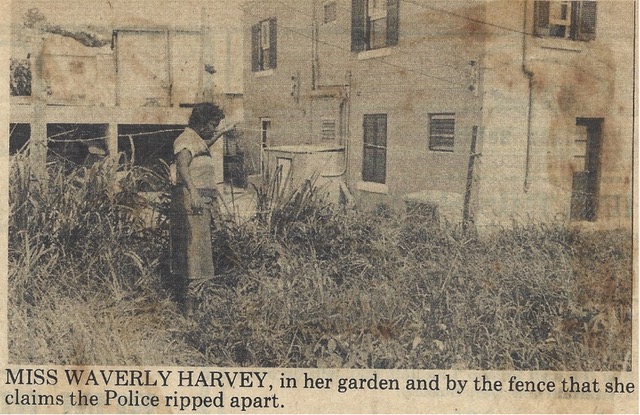

Upset with the Police actions during the raid, however, were two Parson’s Road female residents, who lived next to the two houses where the bust took place. The two women complained that Police had ripped apart their barbed wire fence to gain entry to their large garden overgrown with weeds which they trampled over in an apparent search for marijuana.

The Royal Gazette (RG) in their report the next morning said the women had stressed that they were not taking issue with the raid, but with the presence of Police on their property without a search warrant.

“They completely ignored me,” explained Mrs. Iris Harvey, commenting on the response of the four policemen to her as she stood in her garden.

“That shows pure disrespect. We were getting ready to call the Police, when my granddaughter told me they got out of the garden.”

Miss Harvey emphasized that the Police had no right to be in her mother’s garden without their permission.

Confirming that five men had been arrested on a drugs charge, a Police spokesman also responded to the Harvey’s complaint. He said that the proper procedure would be to lodge an official complaint with the Commissioner of Police Mr. Frederick Bean. “If she had a legitimate grievance,” he said, “I’m sure the Police would be prepared to make reparations.”

Asked whether the Police required a search warrant before going on private property he said: “I can’t comment on this particular case. But under certain circumstances of immediate pursuit, a Police officer can enter private property.”

But even after this bust Chapman’s illicit trading of drugs continued – and the Police had kept up their intermittent surveillance. Chapman was variously police bailed from this arrest until the end April 14, 1982 [just over 12 months] when he was formerly charged with possession of heroin with intent to supply.

1982

In June 1982, Chapman applied to the Bermuda Supreme Court seeking a declaration under the Bermuda Constitution that his constitutional rights to a fair trial had been infringed.

In July the Supreme Court ruled against Chapman and a week later he appeared in court charged with six more offences including conspiracy to supply dangerous drugs.

Alvin Chapman, 37, of Lighthouse Road, was appealing a Supreme Court ruling made against him in July over his application under the Bermuda Constitution. He was asking the Court of Appeal to overturn that judgment and make a declaration that his constitutional rights to a fair trial within a reasonable time period has been infringed. Chapman was represented by lawyers Mr. Michael Mello and Mrs. Priya DeSoysa.

Mrs. DeSoysa argued that the Chief Justice, the Hon. Sir James Astwood, had been “totally misled by the Crown in this matter” and had been confused over the charges laid against Chapman. She also argued that the Chief Justice had started off from the wrong date when making his ruling on the question of a “reasonable period of time.”

Priya DeSoysa-Levers

Priya DeSoysa-Levers

Said Mrs. DeSoysa: Chapman had been arrested on August 6, 1981. He was kept on Police bail until the end of April [1982] when he was officially charged with possession of heroin with intent to supply.

In June [1982] Chapman applied for a declaration under the constitution and then a week later, he was summoned to court again and charged with six more offences including conspiracy to supply heroin and cannabis.

“Police put him on bail. They restricted the appellant’s movements in order to observe him better for a totally unrelated offence, or offences, hoping that he would commit some crime.

“I would submit strenuously that the Police behavior cannot be condoned and should not be condoned in this matter. They were waiting to see if he would commit some crime.”

Mrs. DeSoysa complained that the prosecution then tried to withdraw Chapman’s bail [in April 1982] even though they were not ready to proceed with the case.

She said that the Crown had then misled the Chief Justice during the constitutional application by persuading him that the delay was reasonable to allow Police time to get evidence of a continuing conspiracy.

But the conspiracy charges were completely separate from the possession with intent charge and the Chief Justice should have asked why the prosecution delayed proceeding with the possession charge.

The Chief Justice also mistakenly took the April date when Chapman was formally charged as the “operative” time. Mrs. DeSoysa submitted that the crucial date had to be the date of arrest which was some eight months earlier.

Crown Counsel Charles Quin replied that the Chief Justice was correct in looking at all the charges together. Moreover, he had considered the time delay back to the arrest and [had] not found it unreasonable in all the circumstances.

Mr. Quin said that those circumstances included [the fact that] some three months earlier in the year Chapman had left the country because he was “seriously ill” and had visited Hawaii, Hong Kong, the Bahamas, the United States and Thailand.

The three appeal judges reserved their decision.

1983 – THE SUPREME COURT TRIAL

The three – Alvin Eugene Chapman, 37, of Lighthouse Road, Southampton; Robert F. Trott, 33, of no fixed abode; and Raymond M. Grant, of Parson’s Road, Pembroke; each denied six offences for which they are being tried together. Trott and Chapman each denied an additional charge.

The RG reported that the jury had just been selected when the 12 jurors were asked to leave the court until Thursday while lawyers for the defendants present legal arguments before presiding Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett.

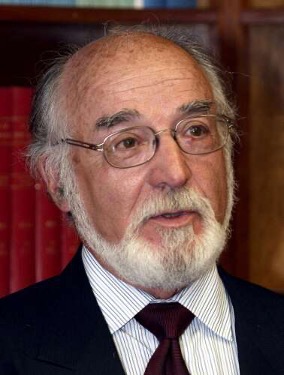

Prosecuting, Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin, estimated that trial may take between three and five weeks.

Saul Froomkin QC

Saul Froomkin QC

Chapman, Trott and Grant deny each of the following charges:

- Conspiracy to supply heroin between February 1, 1981 and April 14, 1982;

- Conspiracy to supply cannabis resin between the same dates;

- Supplying heroin;

- Supplying cannabis resin;

- Handling heroin which was intended for supply; and

- Handling cannabis resin intended for supply.

Trott was further charged with possession of heroin which was intended for supply on August 6, 1981.

Trott is also charged with misusing heroin on August 6, 1981.

The Crown was represented by both Mr. Froomkin and Crown counsel Mr. Charles Quin. Chapman is represented by Mrs. Priya DeSoysa-Levers, and Trott and Grant are represented by Mr. Michael Mello.

This drugs trial was “something very novel”, Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin QC told the jury.

Detectives had kept watch on the Parsons Road house for a period spanning more than a year, taking hundreds of pictures of suspected drug deals from their look-out point in the nearby Evening Light Church.

For the first time in Bermuda’s criminal history, video tapes of crimes alleged by the prosecution will be shown in court.

“Police kept observation on a certain house in Parsons Road, Pembroke Parish, and they took hundreds of photographs which will show, I suggest, drug transactions,” said Mr. Froomkin. “You will also see the actual transactions which are described by Police.”

He continued: “You will hear evidence that of the people who were at the premises virtually all were known drug addicts or drug users…….

“You will hear that this was a supermarket for drugs being carried on in Pembroke Parish with little children running around. You will see it yourself on video.”

He also expected that the court would hear evidence from drug addicts themselves “who will testify as to what they were doing.”

Mr. Froomkin told the jury that Police raided the Parsons Road house on August 6, 1981 and some people were arrested.

But even after the bust the “supermarket” traded on – and Police kept further surveillance.

A number of items were seized during the raid including a leather bag with Chapman’s name on it which contained 28 decks of heroin. “All kinds of drug paraphernalia” were also seized as well as more than 200 pieces of silver foil.

Mr. Froomkin was opening the prosecution case in the trial of three men accused of supplying heroin and hashish. The Crown decided not to proceed with two further charges against all three men of conspiracy to supply heroin and cannabis resin.

The first and only witness this Thursday was narcotics squad officer Dc David O’Meara who had kept a watch on the house at various times between June and November 1981. Dc O’Meara described the Parson’s Road house as a green-coloured two storey building with two garages at the rear and a second residence just behind the garages.

Dc O’Meara produced as exhibits two volumes containing more than 200 pictures of various “transactions” carried on mostly in one of the garages. He identified many of the people in the pictures including Chapman, Grant and Trott. There were also others who, he said, had either confessed to him that they were drug addicts or users, or people he had arrested previously for drug offences.

The people included Kirk D, Nicki S , Erwin Y , Greg M, Michael B , Berwyn D and Conrad P.

Dc O’Meara also described the August 6, 1981 raid. At about 3 p.m., he together with Dc Dennis Gordon, Dc John Wright, Det. Sgt. Alex Arnfield and others went to the back door of the house. The door was open but a screen door [was] closed. “Through the screen door I could see into the building and I saw a number of people together and I recognized the defendants Chapman and Trott who were standing together. Trott had a small plastic bag in his hand. Through the screen door I shouted, ‘Police, open the door’.

“Trott immediately turned and ran into a doorway and went from view. Chapman was carrying a shoulder bag. He threw it on a counter top before turning and running, making off after Trott.

“I pulled at the screen door but it was locked from the inside. I therefore broke the screen with a riot stick and unlocked the door. Inside the room were Erwin Y, Craig H and Kirk D. Dc Gordon went after Chapman and caught up with him.”

Dc O’Meara continued his evidence the following day –

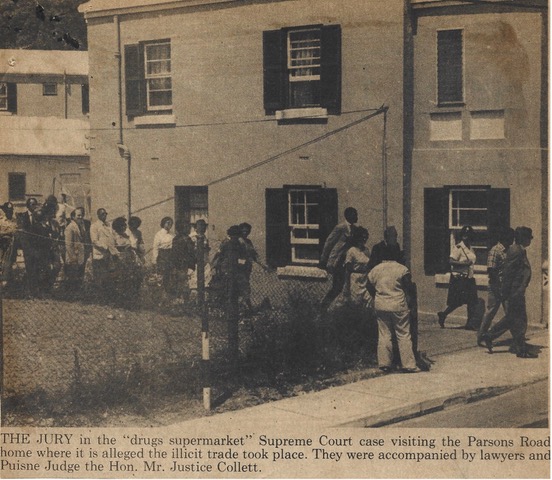

Accompanied by Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett and lawyers in the case the jury were shown a Police observation point from the Evening Light Church and the home of where drug trafficking is said to have taken place.

It was from the church that narcotics officer Detective Constable David O’Meara took 998 photographs during 12 days between June and November, 1981 the Supreme Court heard.

Continuing his evidence, the jury looked at some of the photographs which Dc O’Meara said showed drug dealers and users at the premises and, in some cases, “transactions.”

The prosecution had told how the house was raided on August 6, 1981, and even after arrests were made officers keeping watch saw that the illicit trade continued.

Dc O’Meara said that on entering the house in August, 1981, he had asked Chapman: “Where’s the stash?”

He said Chapman replied: “Ain’t nothing here. Robert’s gone with it.”

The officer later explained to the jury that by asking where the stash was he wanted to know where drugs for sale were being kept or hidden.

The detective said he saw Chapman and Grant in the kitchen. Earlier he had seen [Robert] Trott run off.

Searches were then made of various people in the house.

Dc O’Meara said he found a quantity of money and silver foil decks in the jeans of Irving Y and he was arrested on suspicion of possessing a controlled drug.

Next Chapman was searched. In a leather shoulder bag which Dc O’Meara said he had seen Chapman with, was a twist of brown paper containing a number of foil decks. Inside one was light pink-coloured powder. Chapman was arrested on suspicion of possessing a controlled drug with intent to supply. After being cautioned he said: “Go ahead.” In a bedroom $495 in cash was found under a mattress.

Further searches were made of Chapman’s car and home [at Lighthouse Road, Southampton] and the home of [Robert] Trott.

Dc O’Meara took the jury through a number of photographs pointing out the identity of most people in them. He claimed that transactions were carried out in the yard.

The jury was taken to Parsons Road after lunch at the request of lawyers representing Chapman, Grant and Trott.

Cross-examined by Mr. Michael Mello, for Trott and Grant, Dc O’Meara said some observations on the house were from the early morning until late at night. “It depended on how long the trafficking was,” he said. “If the area was busy we stayed until we were able to leave. Sometimes we were there until midnight.”

The officer said he did not record everything on film as he knew the area was being video-taped.

The prosecution has said that video film will be shown in court and television sets have been set up for this purpose.

The jury has heard that Police had kept watch on the Parson’s Road house for more than a year and had taken hundreds of pictures of suspected drug deals from their lookout point at the Evening Light Pentecostal Church across the road [from the houses].

R , who said his drug habit used to cost him between $75 to $100 a day, identified himself in three photographs shown to him by Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin, QC, who appears with Mr. Charles Quin for the Crown.

Of one photograph he said: “I was wearing black and white. Robert (Trott) is next to me wearing a hat.” He explained that he had gone to buy heroin at about 8.0p.m. before he went to work.

Asked from which of the accused he had bought the heroin, Ronald R said he could not recall.

Another photograph was taken on September 17, 1981. Mr. Froomkin asked: “Did you buy heroin on that day?”

“That’s the only reason I went there,” replied Ronald R.

Said Mr. Froomkin, “You told us that for some years you purchased heroin from the downstairs premises. Who did you buy from?”

Witness replied, “Alvin Chapman, Rudy Grant and Trott.”

He also said that he sometimes got drugs on credit. “Who gave you credit?” Mr. Froomkin asked.

“Alvin Chapman,” replied [witness]

Under cross-examination by Mr. Michael Mello, defending Trott and Grant, Ronald R disagreed that he never bought drugs at all.

Evidence was heard from Dc Maurice Pett, who told of taking photographs from Evening Light Church during an eight-hour period on September 3, 1981. “I arrived at the church at between 4.30 a.m. and 5. a.m.” he said. “It was dark when I got there. There was little activity until 9 a.m.”

Reading from a log which he had kept, Dc Pett told of photographing people who went to and left the premises between 9a.m. and 5p.m. that day. Among the people who came to the house were Lawson R, Conrad P, Pamela L, Curtis D, Mackie B, Sherman M and Nickie S who made two trips.

He said of Pamela L “I took a photograph of this person as she was leaving. I have dealt with her. She is a heroin addict.”

He told of taking a photograph of Lawson R, and when shown an enlargement of the print, he said: “R appears to be passing money to Chapman. Chapman passed something to R in return.”

He also said he saw a transaction between Chapman and a white male, who left with something in his hands.

Under cross-examination by Mrs. Levers, Dc Pett agreed that heroin was a white powder. He went on to agree that the photographs showed neither white powder nor money changing hands.

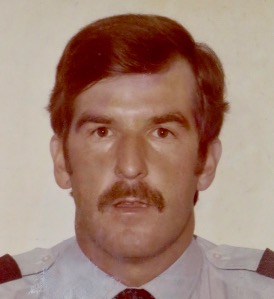

In what was a Supreme Court first, the tapes were presented in evidence by former narcotics policeman Mr. William Henry and were screened in the court on three television monitors.

Mr. Henry told of taking photographs and video tapes of a Parson’s Road house that had been kept under Police surveillance from June 1981 to August 1982.

He said he took a total of 11 tapes, of 42 hours duration, on eight days beginning July 6 and ending November 10, 1981. From those tapes he made a master tape, running two and one-half hours, of portions that he believed were relevant to the case, he said.

Mr. Henry played part of the master tape containing video tapes covering a three-hour period on July 6. He explained that the initial events showed Carla J, a known heroin addict, arriving at the Parson’s Road premises, situated across from the Evening Light Church. “You will see,” he said, “a transaction on tape with Trott handing something to J.”

The video tapes were played, then stopped to allow Mr. Henry to recount the next segment, continuing until the video-taped events of July 6, beginning at 4.40 p.m. and ending at about 8.0p.m. were shown.

While playing the tapes, Mr. Henry named several people, including Michael B, who has since died, Steven P and Kirk D , who were known to be heroin addicts, and other unknown persons as being among those who went to the Parson’s Road house.

According to Mr. Henry’s testimony, segments of the tape showed Trott and Chapman having transactions, and other portions showed children playing in the area where transactions were taking place.

Earlier, Mr. Henry had shown photographs printed from three rolls of film, showing all three accused men taking part at different times in transactions.

Before presenting one photograph, Mr. Henry said: “I observed Alvin Chapman standing up counting money. Betty S is sitting down in a chair. Stanley W is at right. I know Betty S. I have dealt with Betty S on a number of occasions. She is a heroin addict. I have no personal knowledge of Stanley W.”

At the start of today’s proceedings, Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett warned that it was an offence to intimidate Crown witnesses. He issued the warning after Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin, QC, who is prosecuting along with Crown Counsel Mr. Charles Quin, said there was evidence that Crown witnesses had been interfered with.

Mr. Justice Collett said: “Interference with witnesses is a serious contempt of court and will be dealt with accordingly.”

Mr. Froomkin also pointed out that such an offence was a criminal one.

A former heroin addict, 20-year-old Kevin H took the stand and told of travelling to the Parson’s Road house to get heroin for his $50 a day habit. But H , who became a heroin addict at the age of 16 and came off the drug recently, said: “I did not buy it there (the Parson’s Road house). I did not know anybody on Parsons Road. When I needed heroin Eddie P and I used to put money together and Eddie used to get it.”

He would accompany Eddie P to Parson’s Road, but P purchased the drug.

Questioned by Mr. Froomkin, Kevin H said he did not go to the Parson’s Road premises for any purpose other than to buy heroin.

Kevin H identified himself in a photograph taken by Police of the Parson’s Road house from their observation site at Evening Light Church. He said that he rode up with P, who bought the drugs.

When asked why he never took part in a transaction, H replied: “It looked kind of strange for a white guy to be hanging around Parsons Road.”

Mr. Michael Mello, lawyer for Grant and Trott, and Mrs. Priya DeSoysa Levers, representing Chapman, elected not to cross-examine H.

Both had cross-examined R, who denied that he had been offered immunity from prosecution by Police in exchange for testifying. Mrs. Levers pointed out that he had confessed to Det. Sgt. Alex Arnfield about his heroin addiction, but had not been charged for the “crime”.

Presenting the tapes in evidence was former narcotics policeman Mr. William John Henry who described events he video-taped on July 20 and July 29, 1981. Besides the three accused seen on the monitors were people, both known by Police and unknown, who had gone to the Parson’s Road premises. Among those who drove up and left, whom Mr. Henry alleged were heroin addicts, were Steven P, Betty S, William O, Geoffrey L, Lawson R and Dennis M.

Mr. Henry also played a segment of the tape showing Robert H arriving at the premises. H, Mr. Henry said, was a hashish user.

All of Friday’s session had been taken up with the showing of the tapes. Mr. Henry had operated the video-camera from an observation site at Evening Light Church, focusing on activities taking place in front of a green and pink house on Parson’s Road.

In one segment, H and Trott were seen to have an exchange, Mr. Henry said, while another segment saw Trott walking from the area of the green house to his car and emerging from the car with something in his left hand. “He then left in the company of Steven P, and P,” Mr. Henry said.

In another video-taped section, Betty S was seen entering the green house. Minutes later, William O was seen entering the premises, then walking from the yard while putting something in his pants pocket.

“At 11:45 a.m. Betty S left the yard putting something in her pocket,” Mr. Henry continued.

Mr. Henry said he also video-taped Chapman removing something from the front of his shorts and placing it in the ceiling eaves, but because Chapman’s movements were blocked by a telephone pole, he produced photographs depicting the same activity.

Hundreds of photographs had been taken by Police from their observation site.

Another section of the video-tape showed Grant going to the pink house and returning with something in his hand.

The screens of TV monitors placed in the darkened Supreme Court showed that Chapman, carrying a package under his left arm, had just appeared when about half-a-dozen plain-clothes policemen rushed onto the scene. The Police officers could be seen running into two garages and a nearby house where the transactions were alleged to have taken place. Filming was stopped at that point.

This raid had taken place on August 6, 1981, one of the eight days during which Police had video-taped activity outside the Parsons Road house which Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin referred to as a “drugs’ supermarket.”

All three defendants had been arrested as a result of the Police raid, but were released on bail whereupon they were again subjected to Police surveillance on September 11 and 17, 1981, when further alleged drug transactions with known heroin addicts were recorded on video and shown in court.

Mr. Henry described to the court how between 9.30 a.m. and 2.12 p.m. on August 8 he had recorded 60 instances when people would appear on the scene. Those entering the area included known heroin addicts and users. People had been filmed as they entered the area from a window in a nearby twin-garage building set between two houses. Many entered one of the garages and were seen to pick up packages and walk out. Others were seen going into the neighbouring green house and emerging later with packages stuffed into their pockets or carried under their arms.

Mrs. Priya DeSoysa Levers put it to former narcotics officer Mr. William J. Henry that apart from one photograph, nowhere could it be shown that her client Alvin Chapman had been involved in any drugs transaction.

The case has marked the first time video tape screenings have been used in a Bermuda criminal court as evidence.

Scenes from the stake-out of a house on Parson’s Road were shown again in the Supreme Court with Mrs. DeSoysa Levers asking Mr. Henry where they or his notes made reference [to] or showed transactions. She also queried his assumptions that certain people seen going to the house – which was labelled a “drugs supermarket” earlier in the proceedings – were drug addicts because they had been known to be receiving methadone treatment a couple of years earlier. “Are you assuming that people do not change?” she asked Mr. Henry.

“I was working on knowledge at the time,” Mr. Henry replied.

[Former narcotics officer Mr. William John Henry] described as “absolutely false” a suggestion by Chapman’s lawyer that his notes of the stakeout were not contemporaneous because a woman named in them who visited the house had only just arrived in Bermuda and could not have been known by Police.

Mr. Henry said her name was given to him by another officer present at the time and later said, under questioning [re-examination] from Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin QC, that there was a security arm of the Police which kept a check on incoming people.

Mrs. DeSoysa Levers established that Chapman had featured on just three of eight video films and she also asked Mr. Henry if his notes made any repeated references to actual transactions involving him.

Mr. Henry replied on several occasions: “No transaction.”

She wondered why only one of nearly 1,000 photographs taken during the stake-out showed Chapman allegedly handing over something.

Mr. Henry said that he was quite certain of what he had observed and pointed out that it was a question of split-second timing when it came to capturing scenes on camera, but he witnessed events continually through the video and camera view-finders and through binoculars.

Mr. Froomkin in re-examination referred the witness to a series of photographs showing Chapman’s presence on those days he was not videotaped.

Police fingerprint officer Detective Sergeant Keith Cassidy testified that Raymond Grant’s fingerprints had been found on 25 silver foil decks found in a Tupperware container at the house that held a total of 265 such decks. He said there were enough similarities between Grant’s prints and those found to show them to be identical, despite suggestions from Grant and Trott’s lawyer, Mr. Michael Mello, that just one variation could nullify that assertion.

Wearing dark sunglasses Conrad P pointed to Robert Trott and Alvin Chapman sitting in the prisoners’ box as being involved in an alleged drug trafficking operation at [a] Parson’s Road residence.

P identified himself in pictures taken surreptitiously by Police of alleged drug transactions witnessed at the Parson’s Road house labelled earlier in the trial as a drugs “supermarket.” And he described how he would obtain drugs by going to the back door of the house, knock on it, ask for drugs and slip money under the door. In exchange drugs would be pushed out.

“I used to go to the door and put my money down,” said P. “I would say that I wanted two decks and put my money at the bottom of the door, and the drugs would be passed to me.”

Asked by Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin what role Chapman played in the scheme, P replied: “I can’t really say. He was picking up the money.”

P was shown pictures of alleged drug transactions by Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin. In one sequence he identified himself talking to Chapman and asking for credit to buy heroin. “I think I was trying to get drugs, and I think I was trying to talk to Alvin for some credit,” said Phillips. “I think I ended up buying something.”

P told the jury that on occasions Chapman would tell him that he did not have any drugs adding that he could get drugs from Trott.

But on cross-examination by defence counsel Mr. Michael Mello and Mrs. Priya DeSoysa Levers, P became confused about the dates the pictures were taken and conceded they would have been shot over a number of years during which he was a drug addict.

P also conceded that before he got off drugs 18 months ago he had turned to crime to keep his habit alive. He admitted that he had been convicted of shoplifting, and lived off the earnings of a prostitute – his wife.

But before he gave evidence, P told the court that he had been a heroin addict for 15 or 16 years, and had not only gotten off the drug, but was also now a Christian. “I must speak the truth,” he said.

Earlier in the proceedings that day, Detective constable [Jonathan] Smith had been called to the stand next when he related how he and other officers had gone to the Parson’s Road residence on August 6, 1981, while Chapman and others were there. He said they had found, after searching persons there, the premises and two garages, an assortment of drugs-related items including paraphernalia commonly associated with the preparation of heroin, medicine bottles, a syringe, razor blades and a Tupperware container containing a large quantity of silver foil.

Constable [Jonathan] Smith denied a suggestion that Police had “manufactured” evidence against Grant by submitting for fingerprint evidence tin foils that Grant had touched in the presence of Police during a raid on August 6, 1981.

The suggestion had been put to P.c. Smith that some of the 265 tin foils found in a Tupperware container located in a garage adjacent to the house on Parson’s Road bore Grant’s fingerprints because Grant had tried to pick them up when they were accidentally dropped during the Police search.

Smith denied this but conceded that the only evidence connecting Grant to the drugs discovered were the fingerprints.

Mr. Froomkin [then] introduced as evidence 22 copies of the American magazine ‘High Times’ – a magazine devoted to the misuse of controlled drugs. P.c. Smith showed the jury copies of the magazine including two back covers which advertised for sale pipes consistent with the misuse of drugs.

“Are you saying that if you are a reader of ‘Playboy’ then you’re a sex maniac,” asked Mrs. DeSoysa. “Are there any controlled drugs found in that magazine.”

“Of course not,” replied P.c. Smith.

Witness Deborah B said she had been an occasional user of heroin in 1981, and had been to the Parson’s Road premises on six occasions to purchase the drug for use by herself and her boyfriend Winston A.

She described the different ways she had obtained the heroin: three times she had pushed money under the back door of the green house, and the drugs were pushed out. On the other occasions, she had been let inside the house and had purchased the drugs personally from the accused Chapman.

Miss B told Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett she had also been inside the pink house on one occasion, when she had snorted heroin, along with Chapman and Winston A.

Witness Carla J , who said she had sometimes spent up to $600 a day on heroin, identified herself in three of the Police photographs. When questioned by Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin she said she had bought heroin from Trott, and had been given the drug by Chapman on “numerous” occasions.

Under cross-examination by Mr. Michael Mello, defence counsel for Trott and Grant, J denied having told Grant that she had been pressured into making a statement by Det. Sgt. Alex Arnfield.

Mrs. Priya DeSoysa-Levers, defending Chapman, suggested that J had made a deal with Police that she would make a statement in return for them not prosecuting her for possession of a syringe.

She replied: “I didn’t make no deals”.

Dc Dennis Gordon who observed the “drugs supermarket” over a five-month period in 1981, described what he saw at the premises. He said, “I saw the defendants throughout the whole time I was there.”

He described how he had observed people entering and leaving the house, by peering through the windows of the Evening Light Church across the road.

He said there were usually a few people waiting outside for Grant and Trott to arrive in the morning. When they had opened up, he said he saw people leaving the house carrying silver foils, and counting them in their cars, which they parked in the Church parking lot.

Chapman usually arrived an hour or two later, and would come and go throughout the day, wearing a leather shoulder-bag, said the witness. After dark, the pink house would be closed up by the defendants who would leave using flashlights.

Dc Gordon went on to describe what happened on August 6, 1981, when Police raided the premises. He said that after the screen of the back door had been broken, he had climbed through and chased Chapman and Trott as they escaped through the front of the house and onto Parsons Road. He quickly caught Chapman, but Trott made good his escape.

Later that day, Police searched the shed at the rear of the house, with both Grant and Chapman present. They found a square Tupperware container containing silver foils and several small bottles, one of which contained a pink powder. A further search revealed a razor blade and two pieces of glass.

Mrs. Levers pointed out that former narcotics policeman Mr. William Henry had earlier testified that Chapman was not at the premises on September 11, 1981, contrary to what Dc Gordon had said. The prosecution later showed that Chapman and his car appeared in several of the photographs taken that day.

The trial was to continue on Monday, June 6, 1983.

A call was immediately made by United Bermuda Party MP Mr. Maxwell Burgess who stated that a major aim of such a Royal Commission into illicit drugs should be to expose the “big men” behind the thriving trade in Bermuda. “We have got to get the big man,” he said. “Hopefully the commission will find out where the big men are.”

Mr. Burgess said he hoped people who often said they had seen drug dealing taking place would step forward and make their representations. He added: “I can’t wait to find out who the big man is.”

Over a dozen parliamentarians from both parties spoke on the matter when it was revealed that the commission would be a public forum that presented the opportunity to put the focus on the problem.

[Continuing later] Mr. Maxwell Burgess said it would be an injustice if the legislation were delayed any longer and unfair to impose a time frame. “It is my hope that every single person who has valuable input will make their representation to the commission,” he said. [For context and reflection on this point – see below at Tuesday, February 14, 1984]

Mr. Austin Thomas (PLP) said that he understood that the Police knew the major people involved is drugs in Bermuda. “If we are to be serious about it we need to get right in there, he said.

“What attempts are being made to investigate known addicts? It would be wrong to do something just to show that we are spending dollars in an attempt to solve the problem.”

Witness Sherman H , who admitted he was under the effects of the drug while giving testimony, described how he had gone to a house on Parson’s Road on “thousands” of occasions to buy dope. During his court appearance, the 32-year-old father who has a long criminal record, said he was giving evidence so “my sons won’t be like me.”

H , nicknamed ‘Butch’ told the court that he had been turned away from the methadone treatment scheme for addicts some time ago and had to turn back to the streets to satisfy his 17-year-old heroin addiction. Clad in green T-shirt and cut-off shorts, H answered questions slowly and appeared to have difficulty in hearing questions.

At one stage Mr. Michael Mello, representing Trott and Grant, asked the witness if he was under the effects of heroin there and then. H replied that he was.

Earlier H, under questioning from Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin QC, related how, before and after August 6, 1981, he had obtained heroin from the house in Parson’s Road – labeled a “drugs supermarket” during the course of the trial.

He said he had known Alvin Chapman for 18 years and the other two for a long time, but he had never actually seen Chapman involved in any transactions when he had gone to the house for drugs.

“I used to put the money under the door and get the heroin,” H said.

“I heard that the Police had busted the place. I got heroin before and after the bust,” he went on.

He said he went to the house “to sell things” to Chapman and others. He used to get money in return and then got dope.

“I got heroin, but not directly from Chapman,” H said. “It was whoever was giving it – Jimbo (Trott) or Kirk or Raymond.”

H said between 1981-82 he was on “17 bags” a day and that he had been to Parson’s Road “thousands of times” over the years to get heroin.

He added that he had never actually seen Chapman dealing drugs. “He always went into a different room and I couldn’t see what was happening there.”

Mr. Froomkin pointed out that defence counsel had claimed other witnesses were pressured by Police into testifying, but H said that was not his reason.

“It took me about three years to get hooked on drugs. The rest of the time I have been trying to get off them, and I just don’t want my sons to be like me,” H said.

Mr. Michael Mello asked H if he knew what day it was or even the month. H replied it was Sunday the day before and he knew last month was May.

H admitted some of his statements may have been exaggerated or even untrue, but he said he knew what he was doing and he said he had not confused Robert Trott, whom he knew as “Jimbo”, with his brother Richard, also called “Jimbo”, as Mr. Mello had suggested. He disputed Mr. Mello’s assertion that he (H) was totally disreputable and dishonest, saying his record of theft was a question of “survival, not dishonesty”.

Former heroin addict Pamela O , told the court that she had struck a deal with narcotics officer Det. Sgt. Alex Arnfield and he gave her $25 to buy one bag of heroin from the house.

O said that she had been caught stealing liquor and Det. Sgt. Arnfield had promised her that she would not be prosecuted if she cooperated. She said she had carried out her side of the bargain on September 17, 1981, by pushing the money through the door of the green house at the site. A bag of drug was handed out to her.

O told the court that she purchased drugs at least once a day – sometimes two and three times – from the Parson’s Road house during 1981 and the beginning of 1982.

She had known the three accused men “for quite some time” through her husband William who was also a drug addict. The cost of the couple’s combined heroin habit was about $450 a day, she said.

Before the Police bust on the premises in August 1981 she bought the drugs in the garage.

“A few times I purchased from Jimbo (Trott) and Grant and a couple of times from Chapman also.

“After the bust I had to push the money through the door. The hole in the door was sometimes called the cash register.”

O’Connor said she had seen other people buy heroin in her presence from all three accused men.

Lawyer Mr. Michael Mello, defending Trott and Grant, asked O if she felt she would have been prosecuted for the liquor theft if she returned empty handed to Det. Sgt. Arnfield.

“I didn’t know that,” she replied. “I thought I could be prosecuted anyway whether I came back with the bag or with nothing.”

She agreed that Det. Sgt. Arnfield had kept his side of the bargain and she had never been prosecuted for the liquor theft.

Chapman’s lawyer, Mrs. Priya DeSousa Levers, asked O if she had been charged with another liquor theft for stealing six bottles of rum two weeks ago. O said: “No.”

The second addict on the stand this Tuesday was Kenneth S, of Somerset, who started using heroin five years ago and is still an addict. His addiction has had a devastating effect on him, S said. I have lost just about everything that I had worked for. It has made my life miserable.”

He bought his drugs either from Court Street or Parson’s Road. At Parson’s Road he had purchased heroin from all three accused men “on occasions.” He also bought a syringe from Chapman.

S had not been given any promises to testify at the trial. “I am giving this evidence because I am tired with this life. I did not know what I was getting into from the beginning and I think the more knowledge that the kids and parents get from this might save them. I hope to save at least one child by going through what I did.”

Under cross-examination from Mr. Mello, S agreed that he was sentenced in Magistrates’ Court last Monday for drugs and breaking and entering offences.

Mr. Mello suggested that the sentence he received was “very light indeed, a suspended sentence”.

S replied: “I don’t know if it was light. It was a suspended sentence.” S had been given a six-month suspended sentence and a $900 fine.

William O, husband of Pamela O , who aided police investigations in exchange for charges of theft against her being dropped, took the stand for the prosecution. He told the court how he or his wife would go to the Parson’s Road residence to buy heroin to support his $450-a-day habit in 1981 and 1982. He identified Alvin Chapman, Robert Trott and Raymond Grant as the men who had sold him the drugs.

The last witness for the prosecution was Det. Sgt. Arnfield who headed the investigation of the Parson’s Road house – labeled a “drugs supermarket” throughout the course of the trial. He said that both R and K had jumped bail and fled Bermuda after they had been charged with serious drug offences.

Det. Sgt. Arnfield said he had not made any deals with any of the addicts who have given evidence in the trial apart from O , and he said he had been “pleasantly surprised that so many (heroin addicts) wanted to cooperate with Police.”

Mr. Michael Mello, defending Grant and Trott, accused Sgt. Arnfield of having a “single minded obsession” to get evidence and of threatening addicts with prosecution.

No witnesses were called for the defence, and the three defendants elected to give unsworn statements from the dock, in which each of them asserted their innocence of the charges brought against them. They were not therefore subject of cross-examination.

Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin, representing the Crown, said during his summing up that the evidence against the accused’ was “overwhelming,” and he was sure there were “no innocent explanations” for the 1,184 photographs, the videotaped films, and the evidence of the heroin addicts who took the stand.

Mr. Mello asked the jury to be sure “beyond all reasonable doubt” that the alleged drug transactions were not really innocent exchanges of such things as pieces of chicken and cigarettes.

“I am asking you not to believe them,” he said. “I would believe a Boy Scout who came here and gave evidence. Can you believe that these criminals came here to do good deeds. I think it is sick. I think it’s disgraceful. Would you like to sit there and have your future decided by such evidence?”

Mr. Mello during his final address said the three legs of the rotten stool were represented by photographic evidence including videotapes; forensic evidence and the evidence of the heroin addicts.

Of the photographs and videotapes which Police said showed the three accused in drug transactions, Mr. Mello remarked, “This leg is built on speculation. The Police are saying, “This is what I saw. This is what I want you to see.” When they gave evidence [undecipherable] means something that becomes clear or an apparition. This leg of the stool is an apparition. If you don’t believe it is an apparition, it’s a very rickety leg.”

The forensic evidence, which were Grant’s fingerprints found on silver foils showed only an indirect connection, he alleged. The stool’s third leg – the evidence of the heroin addicts – was dangerously rotten.

He asked the jury to consider [the] evidence. “Colin R said he was a heroin addict for 10 years,” he said. “Yet if you look at his record, there is not one conviction for heroin. There is no drug conviction at all. He had admitted that he had been arrested for drugs. That suggests to you a reason why he came.”

Pamela O , he continued, said she had stopped taking heroin. But when questioned about her needle marks, she said she had been to the hospital for blood tests. “You are asked to believe her,” he said.

Mrs. Levers questioned why Police did not bring to trial the heroin addicts they observed taking part in the alleged transactions at the Parson’s Road premises which they had kept under surveillance for more than a year from an observation point inside Evening Light Church. “If some man was raping people in houses in Tucker’s Town, Trimingham Hill, even Parson’s Road, are you going [undecipherable] for a year, she asked. “These are some basic questions that remain unanswered. If you condone the Police behaviour in this case then each one of us can decide we have no protection whatsoever.”

Criminals walking free,” she continued. “Churches being used. If they were on site, why didn’t they arrest anybody. Sgt. Alex Arnfield and his [undecipherable]. She also said neither the videotapes nor the photographs showed her client involved in a transaction and went on to call the heroin addicts liars.

“These people have reason to lie, she alleged. The video’s show nothing, the photographs show nothing [undecipherable]."

In his final address to the jury Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett directed the panel to return not guilty verdicts in the case of the charges against all three men involving the handling and supplying of cannabis resin.

Referring to Mr. Mello’s division of evidence into three categories, Mr. Justice Collett said: “I would prefer to regard there being five such categories.” They were the circumstantial evidence and the photographic and videos, the direct evidence of addicts and former addicts, the fingerprint evidence, the scientific analysis of exhibits of August 6 and the evidence of Pamela O.

He warned the jury that when considering the evidence of the addicts, they should think about whether they had a motive in giving evidence. It was possible to consider those who pushed money under the door at Parson’s Road as accomplices to a crime, he added.

“With regard to accomplices,” he said, “the law says is it dangerous to convict on their evidence unless it is corroborated.”

He continued his address the following day after which the case went to the jury.

The jury foreman told Puisne judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett that the seven women five men jury could not reach the mandatory majority verdict of ….. [undecipherable.]

Justice Collett had earlier told the jury that it would be dangerous to convict Alvin Chapman, Robert Trott and Raymond Grant on the evidence given by heroin addicts “without corroboration.”

But he added that the evidence in the trial was very extensive.

He outlined the testimony given by several self-confessed addicts during the trial, singling out Butch H and his “significant admission” that he could not swear on the Bible, though his statements were true. Several of the addicts, Mr. Collett said, had admitted that a heroin addict would do anything to stay out of jail.

Chapman 38, of Lighthouse Road, Southampton, Trott 33, of no fixed address, and Grant 30, of Parson’s Road, [had been jointly charged] with supplying heroin and handling heroin with intent to supply between February 1, 1981 and April 14, 1982. Chapman had also been charged with intent to supply on August 6, 1981, and Trott with misusing heroin on the same day. Chapman was defended by Mrs. Priya DeSoysa Levers, and Grant and Trott by Mr. Michael Mello.

Mr. Collett reminded the jury that the unsworn statements from the dock given by the defendants were “a sort of halfway house” between a sworn statement from the witness box, subject to cross-examination, and no statement at all. He said the defendants’ statements were to help the jury “assess the weight and credibility of the evidence”, and understand the defence. He had advised them to consider their verdict “calmly and dispassionately.”

Mr. Collett ordered that the three men return to Supreme Court on July 4 when a date for a new trial would be set.

1984

Mr. Turner-Samuels, who last year represented psychiatrist Dr. Neville Marks and his wife Lana in their appeal against immigration convictions, has been retained by the local law firm of Mr. Richard Hector for the retrial. He will be representing Alvin Chapman, Robert Trott and Raymond Grant, who are accused of supplying heroin and handling heroin with intent to supply.

The case, has already been to trial once before – in June of last year – but a retrial was ordered because of a hung jury.

Chapman was at that time represented by Mrs. Priya DeSoysa Levers, while Trott and Grant were represented by Mr. Michael Mello. Both have since withdrawn from the case.

Last year’s trial was a landmark case because video films of alleged drug transactions were allowed to be shown in court for the first time.

The first trial held last summer ended in a hung jury.

Mr. Collett ruled that he had jurisdiction to order a special jury. He said that the trial would be protracted, complicated, and involve prolonged examination of documentary evidence – all grounds for granting a special jury.

Mr. Froomkin had argued that the previous trial had taken 17 days and had involved the examination of 50 exhibits including portions of some 42 hours of videotaped evidence, and 1,150 photographs. A total of 18 witnesses had taken the stand during the trial.

Mr. Turner-Samuels argued that the judge had no jurisdiction to allow a special jury because the trial had already started. “The issue is this – has the court power, once the defendants are put in charge of a jury, to discharge that jury,” he asked. “The trial of this matter began upon arraignment and”, he said, “it would be an extraordinary position of a criminal code that the Crown or a defendant, having elected trial by ordinary jury, and being dis-satisfied, can then say this time we would like a second shot with a different type of jury.”

He also argued that the trial would not be protracted, would not involve prolonged examination and would not be of a complicated nature.

The trial was to start on the following Monday.

The church’s windows were later all smashed by vandals who also, presumably, protested the police methods used.

The first trial, held last summer, had ended with a hung jury and this new hearing began with Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin QC, addressing the special jury.

He told them they would almost be an eyewitness to those events because they would, in the course of the proceedings, see some 1,184 photographs taken by Police of alleged transactions.

The jury would also view video films, again shot surreptitiously by Police using the cover of a church across the road from the supermarket.

“You will see the actual comings and goings of at least 60 different known heroin addicts and a great number of other unfortunate souls going there for whatever reason and who were unknown to Police,” Mr. Froomkin said.

After the video and camera shots were taken, he went on, Police “swooped down” upon the premises and arrested various persons.

“One would have thought the accused would have realized the party was over, but you may be amazed to discover that not long after, and with Police back carrying out surveillance, the accused’ are back again selling in the same way as before,” Mr. Froomkin said.

“You will also hear from some of those heroin addicts who were photographed and videoed who will testify that they were there to buy heroin from the accused.”

During his evidence Dc O’Meara related how in June, 1981, and on subsequent days for a period of months, he had recorded the events at the Parson’s Road premises with a camera and notebook from a vantage point in the church across the road.

“I had taken more than 900 pictures,” he told the jury. “At first I used to arrive at the church between 4.30 a.m. and 5.30 a.m.,” Dc O’Meara said. “There were times when I was not able to leave until around midnight because of activity in the road outside.”

Crown counsel Mr. Charles Quin, also appearing for the prosecution, asked Dc O’Meara to describe the photographs he had taken. That took up most of the morning and all of the afternoon at the Supreme Court and continued into the following day when he referred to alleged “transactions” he had seen at the supermarket. He said some of those who visited the premises were either known to him then, or had since become known to him as drug users.

Defence lawyers Mr. David Turner-Samuels QC, and Mr. Richard Hector rose on occasion to express concern that Dc O’Meara was interpreting the photographs as transactions rather than simply saying what he saw.

Later in the afternoon Mr. Hector also voiced concern that one of the Police officers who had made a deposition (statement) in the case and who could be a potential witness was present in the courtroom.

Mr. Turner-Samuels said it would not be desirable if any officer who could possibly be a witness was present in the court during Dc O’Meara’s testimony.

Mr. Froomkin, however, rose to assure Puisne Judge the Hon. Mr. Justice Collett that the officer concerned had not appeared in the previous trial and would not be called by the Crown as a witness in the current proceedings.

The trial continued the following Thursday morning when the special jury heard the details of an eager – but less than perfectly executed – Police swoop on a “drugs supermarket” on Parson’s Road last August 6.

Dc O’Meara admitted that he himself became confused “in the heat of the moment” and failed to guard his assigned post – allowing one of the suspects to run away.

Under cross-examination by Mr. David Turner-Samuels QC, O’Meara said [police officers] began congregating across the street from the house, in the Evening Light Church, at about 4.30 a.m. on August 6. The officers arrived in shifts, so as not to arouse suspicion, and by 5.30 a.m., “ten or 11 officers” were in position at the church.

“We expected a number of persons to be present on the property, and we also expected resistance,” Dc O’Meara said. “We wanted as many officers as possible present.”

The narcotics officers telephoned for additional reinforcements just minutes before charging across the street, he said – bringing the total number of officers involved in the raid to more than 20. He said they had planned to wait until hearing the sound of the engines of the approaching Police vehicles before advancing on the house. Unfortunately, the first vehicle to come along was a private car.

“But by this time we were committed, so we went ahead,” Dc O’Meara said.

Mr. Turner-Samuels suggested that Police must have had a good idea of who was in the house they were raiding. “Did you have officers at the front door and the back door?”

Dc O’Meara: “No, that is why Mr. Trott was able to run away.”

The defence counsel asked him “how on earth”, in an operation of this importance, something as basic as that could have been overlooked.

Dc O’Meara: “The officer assigned to the front door in the heat of the moment got his instructions confused. I know, because I was that officer.”

He also described how another officer, finding the kitchen door of the house latched, tore a hole in the top half of the screen and climbed through – cutting his arm – instead of breaking the catch with his riot stick.

Dc O’Meara conceded the officer’s action “did surprise me”, but insisted: “That’s the way it happened.”

Earlier, Mr. Turner-Samuels reviewed with the narcotics officer some of the hundreds of photos he had taken of the “drugs supermarket” and its patrons. He suggested to Dc O’Meara that a series of photographs taken of Chapman in the yard of the house really showed him urinating – not passing packages of drugs through a fence, as the narcotics officer claimed.

“Here he is,” Mr. Turner-Samuels said, indicating Chapman in the picture, “coming out with the thoughtful look of a man who has just relieved himself.”

And the British QC pointed out that in the subsequent photos, Chapman appeared to be experiencing difficulty with his pants – which had “bulged open” at the fly. “I suggest that what these photos show is him trying to eradicate the trouble with his zipper,” he said.

Dc O’Meara said he did not agree, nor did he accept that the “light coloured object” he had seen in Chapman’s hand was really light glinting off his fingernails as Mr. Turner-Samuels suggested.

The 32-year-old Bermudian now attending college in the US, said that while on the Police Force he spent a year on Court Street patrol which involved providing security at the methadone at the clinic at St. Brendan’s [hospital]. “It took me into daily contact with addicts,” Henry said. He said from this experience he was able recognize on sight many of the people who appeared on the photographs taken from 8.28 a.m. until 6.20 p.m. that day from a vantage point in a church across the street.

Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin asked Henry if he could tell [the court] how many addicts or users he saw. “Eighteen known drug users or addicts,” he replied.

Henry described how he watched drug users giving money to the three defendants in return for “items.” On several occasions, with the help of binoculars, he was able to see “drugs supermarket” customers slipping foil papers into their pockets, or wrapping bits of foil up in paper.

Earlier in the day, the jury heard evidence from Colin R, an admitted heroin addict who featured in several of Henry’s photographs. R said he had purchased drugs at the Parson’s Road property on several occasions. “The back door had a kind of mirror in it. I couldn’t see in, but whoever was in[side] could see out. I would push my money through a hole at the bottom of the door, and they would push the heroin out through the same hole.”

Lawyer Mr. Richard Hector, defending, asked him if he had been promised immunity from prosecution in return for testifying. “You were, were you not, admitting to committing a criminal offence” Mr. Hector said. “Did you not think you would be prosecuted?”

Colin R – “No, not six months later.”

Former narcotics officer William Henry gave detailed testimony of films he took on two days, July 20 and 29, 1981.

Puisne Judge Mr. Justice Collett, the special jury, counsel and defendants watched a series of clips of colour video film shown by Henry on four televisions, strategically placed about the court room. The blinds were kept closed throughout the sessions and the lights were dimmed whenever Henry used a tape to illustrate his evidence.

The video camera he used was placed in the Evening Light Pentecostal Church in Parson’s Road which afforded a partial view of two houses, one pink, one green, with a shed building between them. It is this area that allegedly contained the “drugs supermarket”.

Henry, who is now a student in the United States, explained to the court that on occasions he had taken up separate positions and watched events with a pair of binoculars rather than looking through the camera viewfinder. He had listed the comings and goings of people in the yard visible from the church on the two days and described the movements of Chapman, Grant and Trott.

Answering questions put to him by Attorney general Mr. Saul Froomkin, Henry listed the activities and visits he saw on July 20, including the arrival of Grant and Trott at 10.31 a.m. He told the court there followed a series of visits, most of which lasted one or two minutes. A number of times he identified visitors as heroin users or addicts.

He described one visit thus:

“An unknown male entered the yard and spoke with Robert Trott. Trott got out of his car and went into the right hand shed. Shortly after he emerged with something in his hands and then appeared to be counting out something. Trott then handed something to the unknown male and received cash in return.”

On another occasion he said he saw Grant go three times within 11 minutes to the side of an area next to one of the houses, eventually emerging with something in his hand which he gave to Trott. Trott, he said, had a transaction with a man named Robert H immediately afterwards.

He then told the court about other visitors on that day and July 29 and named some as people he knew to be heroin addicts. These were: Steven P, Eddie P, William O, Betty J S, Butch H, Andrea R, Richard G, and Winston A. He named John S as a heroin user and Henry M S as a drug user.

On one occasion Henry said he saw Chapman place something under the eaves of one of the house roofs but admitted that this movement was obscured from the camera by a telegraph pole and he had seen it through the binoculars. He identified six photographs which, he said, described this incident.

In the afternoon, Mr. Justice Collett, court officials, counsel for the Crown and for the defence, the defendants and the jury were taken to the church in Parson’s Road where they saw the site where the Police surveillance was carried out. Afterwards they crossed the road and looked around the yard which had been the subject of the morning’s evidence. They also looked in the kitchen of one of the houses.

On Wednesday, February 1, 1984 a Supreme Court jury heard that a total of 70 people visited a so-called drugs supermarket on a single day in 1981 – and more that 20 of these were known drug addicts or users. Former narcotics officer William Henry made the claim as he went through notations and video footage he made of alleged drug deals at a Parsons Road premises.

During the day’s proceedings, jurors sat in the darkened court and watched flickering TV screens. In the videos shown, men and women, arriving in pairs or singly, walked, rode and drove up to the Parson’s Road premises, disappeared into a green [coloured] house at the side of the yard, and re-emerged minutes later, some clutching packages, others stuffing items into their pockets.

Several women arrived with children in tow, and a number of the visitors made return visits during the course of the day. Henry told the court that on July 29, [1981] as he kept watch from the Evening Light Pentecostal Church across the road, he saw the three defendants disappear 17 times through a gap in a fence behind another pink house on the property.

The former narcotics officer said that on a number of occasions the men emerged from behind the building holding packages in their hand. In addition, on the same day the defendants paid no less than 11 visits to a chair in a shed in the yard – either sit on it, or rummage around under it.

Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin asked Dc Henry how many people had visited the property while he kept his observations that day.

“A total of 70 different people, not connected with the family or residents on the property, and not including the defendants, visited the premises,” he said.

Dc Henry said that from his work at the methadone clinic, during his stint as a narcotics officer, he was able to recognize 21 of these people as drug users or addicts. He also said he took video films on the morning of August 6 [1981] – the day plain clothes detectives had raided the house. As before, the film footage showed visitors thronging to the property, and the three defendants tracing and re-tracing their steps from the green house to the chair in the shed to the hole in the fence. People bustled in and out of the green house – with the majority of the visits lasting less than two minutes.

In addition, the Supreme Court got a fleeting glimpse of the bust itself, which got underway at just after 2 p.m. The jury saw narcotics officers, bundled in bulky bulletproof vests, charge en masse onto the property – which was for once deserted – before Dc Henry’s visual testimony came to an end.

Dc Henry said that on the 16 occasions he had maintained surveillance, he had spotted 60 different heroin addicts or users.

Mr. Turner-Samuels questioned the reliability of Henry’s observations. He also queried Henry’s use of the present tense in his frequently used statement about visitors to the yard: “I know him to be a heroin addict.” Henry said his use of the present tense was based on the notes he took at the time and knowledge he had at the time.

Mr. Turner-Samuels in his cross-examination asked exactly when the former officer had known the people in question to be heroin addicts or users.

Henry said he had seen them on the methadone program in the summers of 1978 and 1979.

Mr. Turner-Samuels, listing one of the individuals Henry had cited as addicts or users, asked: “Are you prepared to say that because you had seen him during that period, he was still an addict in 1981?”

“In 1978 to 1979 he was an addict. I did not see him at the program in 1981,” Henry replied.

“So when you say he is a heroin addict, you mean not that he is to date, or was in 1981, but that he was two years before that?” the lawyer demanded.

“Yes. I would not like to say he was one in 1981,” Henry said.

Later, referring to still photographs taken by the then surveillance officer, the defence lawyer suggested that Henry had not been careful with photographs he had taken and had not shot any “transactions” as the actual exchange too place.

Mr. Turner-Samuels also suggested that the officer was quick to “jump to conclusions” about people in the video films clutching things in their hands.

Henry said that was totally false.

William O, was called as a witness in the so-called “drugs supermarket” trial by Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin QC. He told the jury he first took heroin more than ten years ago.

During his cross-examination by leading defence counsel Mr. David Turner-Samuels QC, William O angrily told the court:

“Being a drug addict is a nasty game. I have begged, I have stole. I have borrowed and I just cannot remember what happens from day to day. All I can remember is getting high.

“I am trying to clean up my act but you’re taking me back years and I can’t remember. You guys are used to dealing with figures and times but I just live from day to day, getting high. I am trying to tell the truth, so don’t make fun of me.”

Mr. Turner-Samuels hastened to reassure William O that he was not making fun but the witness continued:

“I remember some things because drugs have destroyed my life. I cannot forget something that has destroyed my life.

“I never knew what a courtroom looked like until I started dealing with drugs. I am tired of playing that game.

“When I started shooting drugs I had a bank book, I had a car, but drugs gradually took all that away from me. You know why, because it’s a deceitful game.

“It takes your pride, your personality. It takes all of that from you. If a man cannot respect himself how can he respect others? He cannot do it.”

He was giving evidence in the trial of Alvin Chapman 38, Raymond Grant, 30, and Robert Trott, 33 ……

In evidence-in-chief, witness William O told the court that he had been using heroin for the past 11 years although for a two-year period he had managed to break the habit.

He explained the procedure that heroin addicts follow when preparing a fix and said that he normally used a disposable syringe which he would use several times.

He would “cold shake” heroin with water in a spoon, increasing the latter ingredient on the many occasions he shared “fixes” with his wife, P.

He said he would then draw the solution into the syringe and inject it into a vein. He showed the “tracks” – needle marks – that he carried on the skin of his arm.

In 1981/2 he and his wife were getting through seven or eight decks of heroin a day, he said. He identified and named all three of the accused and said he had bought heroin regularly from “either of the three”.

He identified himself in pictures taken of the yard alleged to have formed part of the Parson’s Road “supermarket”. He said that he or his wife went for heroin to Parsons Road every day.

William O said that in a typical transaction he would place money through a hole at the foot of a door and would receive drugs in return. His wife, giving evidence later, called this hole the “cash register.” He told Mr. Turner-Samuels he had last had a “fix” about a month ago.

During cross-examination by Mr. Richard Hector, for the defence, he denied making a deal with Police Sgt. Alex Arnfield. He also denied that he was “high” in the witness box. He admitted that he had once been taken to a lawyer to discuss bringing a complaint against Sgt. Arnfield for harassment.

During re-examination by Mr. Froomkin, he said that he had been taken to the lawyer by Mr. Kirk DeRosa but had declined to sign the complaint. He had been given lunch, he said, and money.

In response to another question from Mr. Froomkin, he replied: “The first place I ever got heroin was Parson’s Road . . . from Alvin.”

William O was followed into the witness box by his wife, Pamela, 27, the mother of his three-year old daughter. She told the court she was a heroin addict and had been so for five years, about the same time as she had known the accused, whom she identified. She said that on one occasion she had been given $25 by Sgt. Arnfield to go to Parson’s Road to buy heroin. She did this and later returned to him with the “bag” she had bought.

Witness Pamela O admitted she was anxious to agree to a Police suggestion concerning an alleged “drugs supermarket” at Parson’s Road in the hope it might help in the theft matter.

But she said Detective Sergeant Alex Arnfield had only said he might try to help. Pamela O said she wasn’t sure whether that assistance would be forthcoming if she cooperated.

“But I was anxious to try,” she agreed during cross-examination by defence lawyer Mr. David Turner-Samuels.

Pamela O told the court that she had been a heroin addict for five years. She identified the accused’ and said that on one occasion she had been given $25 by Sgt. Arnfield to go to the Parson’s Road, Pembroke premises and buy heroin. She did this and returned to him with a bag she had bought.

Mr. Turner-Samuels referred to a visit she paid to Police headquarters on September 17, 1981, when she met Arnfield and a woman Police officer there.

Pamela O said she went there because of the stealing charge. She said she was there for about four hours. “He told me that he would try to help me with this charge. He did not say he could get me off but said he would try to help,” she said.

“Did it not occur to you that this was a strong hand, that he might be able to make things better for you, to put in a good word for you in certain circumstances?” the defence lawyer asked.

“No. I appreciated him telling me that he would try. But at the time I did not know whether things would go in my favour or not,” she replied.

“Would it not be right that Sgt. Arnfield made a promise to you not to have to go up for that liquor case?” Mr. Turner-Samuels asked.

“No, he did not make a promise. He said he would try to see what he could do,” Pamela O said.

Pamela O had left Police headquarters that day to visit the Parson’s Road premises.

Mr. Turner-Samuels suggested that Pamela O had not seen any of the accused on that day. She said she had.

The defence lawyer said the witness had changed her story on several counts from previous evidence.

“No,” she replied. She went on: “Why would I be so proud to come up here and tell people I used to buy heroin? Why should I come up here and lie about something like that? It is nothing to be proud of.”

Mr. Turner-Samuels said he was not suggesting it was something to be proud of but said it might be something that could help in other matters she had with the Police.

Defence lawyer, Mr. Richard Hector, also said that he thought Pamela O had made a deal with the Police.

“I am going to suggest to you Mrs. O that you are now merely fulfilling your side of a bargain,” said Mr. Hector.

“I don’t know why you say that,” said O as tears came to her eyes. “I’m just here to tell the truth.”

Pamela O told the court she was testifying so that her three-year-old daughter would not have to go through the same things as her mother.

Following O, another admitted heroin user took the stand.

Witness Debbie B told the court that she had been a heroin user since 1980. She said that during the summer of 1981 she had visited the site at Parson’s Road “five or six times” to buy heroin.

When questioned by Crown Counsel Mr. Charles Quin, B told the court that on four occasions she and a friend had been invited into the houses at the site to snort heroin. She said that on all four occasions the drug had been supplied by Chapman, and on one occasion Chapman had used the drug himself.

Mr. Turner-Samuels pointed out to B that in the previous trial, she had only mentioned snorting heroin in the houses on one occasion. He asked why she had not mentioned the other three times.

“I wasn’t asked,” she replied.

Det. Sgt. Alex Arnfield, the senior officer in charge of the surveillance, and eventual raid, on the Parson’s Road premises, told the Supreme Court he met with heroin addict Pamela O at Police Headquarters on the afternoon of September 17, 1981.

“I asked Pamela O to go to the green house on Parson’s Road with $25 I gave to her and buy whatever it was they were selling.”

Sgt. Arnfield said he had known both Pamela O and her husband, also a heroin addict, “for long time”.

Sgt. Arnfield said Pamela O had been arrested some time previously for stealing three bottles of Scotch from a Hamilton shop.

“I asked her to take the money and buy drugs for me, and I told her it might be possible to assist her with her charges, but I made no promises.”

Attorney General Mr. Saul Froomkin asked Sgt. Arnfield if he had done this on his own initiative.

“I’m not entitled to take such action on my own,” the narcotics officer said. “I spoke to my superiors, who I believe spoke to someone in the Attorney General’s chambers.”