The story also reveals the nerve and seamanship displayed under difficult weather conditions by numerous local fishermen and a lone Bermuda marine police officer together with a private pilot, all of whom risked their own safety during the search and rescue operation which they launched some 12 hours after the tragedy had occurred.

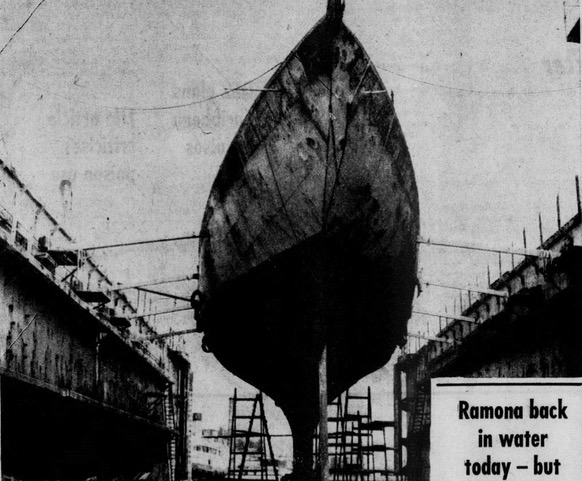

Also documented below are the tenacious efforts over the ensuing years by three local men who purchased and salvaged the floundered yacht. Due in the main to matters over which they had little control, it became an immense challenge for them to finalize their dreams of continuing Ramona’s voyage beyond the horizon and into the open oceans.

Admirable to the end was the trio’s relentless hard work and determination to succeed, as they grappled with all that was laid before them by Island bureaucracy, and mother nature in particular. In the end their pursuit was not the glorious affair it had set out to be, but their undertaking had, nevertheless, proved them worthy of their effort.

During my research and compilation of this narrative, I was most fortunate to have the valued assistance of Stephen Dallas the sole survivor of the trio, together with John “Jack” Chiappa JR. whose father, John Chiappa SNR. has since passed away leaving “Jack” to recall his own memories of assisting the trio in their endeavors. I found both seafarers keen-minded with detailed memories of their experiences with the Ramona during the late 1960’s – as if they were reliving an experience from the day before. In particular, I was able to capture from Steve Dallas many aspects of the tragedy not otherwise publicly known and which have substantially enhanced the reported accounts of the time. Those insights are recorded below as – COMMENT from Steve Dallas 2023. The third member of the trio, Rudolph "Silks" Richardson is also deceased.

NOTE: You will see that the terms ‘barquentine’, ‘brigantine’ and ‘schooner’ are frequently used interchangeably in news reports of the day. In simple terms, the differences in this nautical parlance have to do with the set of the sails on the vessel in question. There are also references to the name “Ramona” and “Ramona C” – for the avoidance of doubt both such names refer to same vessel at various periods during its forty-seven years sailing around the globe.

NOTE: Unless otherwise stated, all news reports on the dates below refer to the Royal Gazette (RG) as the source.

Throughout reports of the tragedy – including the report of the Marine Board of Inquiry – there remains to this day considerable ambiguity surrounding the spelling and arrangement of the names of the three deceased St. Lucian crew members. Research efforts are underway to more accurately identify by corrected name the three St. Lucian sailors named below – two of whom are known to have been teenagers:

- Louis Martin Francis DEPARESTE / DEPAREST / DEPARTEST / DEPARTESTE / / DESPARESTE / DESPAREST

- Hendrickson Rene / Rene Hendrickson / also seen as Henrickson, and

- Winston Thomas Simon or Thomas W. Simon

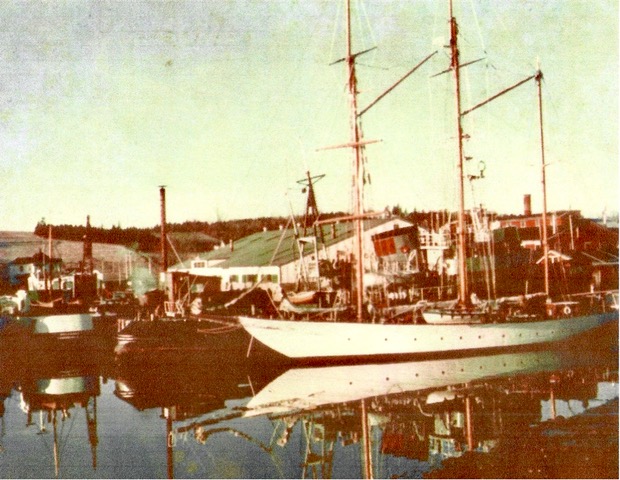

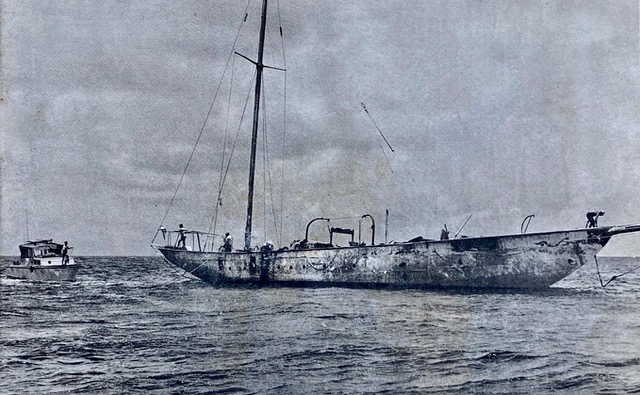

Ramona in Lunenburg immediately following

Ramona in Lunenburg immediately followingFive days later – at about 8.0 pm on the evening of Saturday, December 2 – the Ramona floundered on the reefs north of Bermuda with the tragic circumstances described below.

As the news filtered throughout the community, the heavy pounding of north-westerly waves could still be heard along the North Shore following the aftermath of widespread damage throughout the Colony from the continuing unexpected high winds and tides which had begun on Friday.

The tragedy had stricken the impressive looking 120-foot yacht, at around 8 p.m. on Saturday night when she ran aground on the white-capped reefs near the blinking North Rock light. In a desperate bid for life the crew had sent up all the flares they had on board but, strangely, their signals went unnoticed. Finally, the survivors decided to abandon the steel hulled barquentine lying at a crazy angle on the reefs and, after breaking out life jackets, they eventually took to small boats.

By this time a fleet of small boats were combing the area in a vain bid for survivors. They were being helped from the air by a four-engine U.S. Air Force HC-130; a U.S. Navy helicopter and a civilian aircraft piloted by ex-R.A.F. flyer and lawyer Mr. John Ellison. As the search went on, bodies of the rest of the crew were picked up and ferried to the shore. Also brought in were pieces of debris from the white schooner. Patrol cars took the wreckage to police headquarters for later examination.

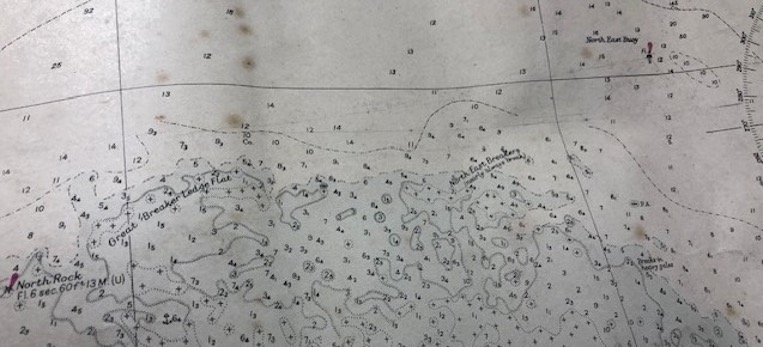

According to a description given by Mr. Ellison the overall wreck site when viewed from above, was of the vicious reefs of the Great Breaker Ledge Flat, with the high ocean swells breaking over them.

The Ramona had departed Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, on November 27 and was heading to St. Lucia to begin winter cruising. She is thought to have been battered by recent storms and was putting into Bermuda when disaster overtook.

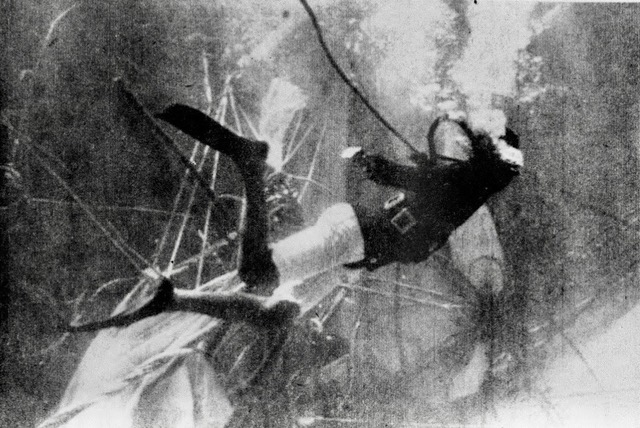

The trio actually boarded the vessel and managed to recover the compass, a pair of binoculars and some other articles. Said Mr. Cox: “I asked permission from Harbour Radio as to whether or not there were any articles of value which her owners might want to retrieve. We decided to dive after the captain requested his log book and asked for the general condition of the vessel." [It is unknown whether or not the Ramona ever carried a ship’s bell or clock but no such items were ever recovered in subsequent years.]

Said Mr. Cox: "Her rudder has been wrenched off but her entire starboard side is undamaged. The port side is lying on top of the reef and the only way to determine how much damage has been caused is by someone going inside her. Conditions made it absolutely impossible to make this type of examination. The dive was exceptionally dangerous and to go any further we would have run the risk of maximum danger.”

Mr. Cox said that he had asked the skipper if he could be of any further assistance. “I will ask if there is anything of value to the crew and I will dive if conditions have improved.” It was only after having completed their dive and returning to their boat, that the three men had discovered a delayed message from two U.S. Para-rescue men advising that conditions that day were prohibitive of their rescue should it have been necessary.

The mystery of why the Ramona did not send S.O.S. messages had been a talking point with local boatmen – but that would be clarified in the days ahead.

After being warned of the shipwreck, Harbour Radio officials alerted several key people in the search – “And the rest came up on the radio and asked if they could help.”

The search, which was coordinated by Acting Police Commissioner Francis (Frank) Williams, was called off after the last body had been taken from the water shortly after noon. The deceased were taken to the King Edward mortuary. The circumstances which led to the tragedy continued to be discussed, although no one could pinpoint the cause. Captain Taylor said that he thought that a mistake had been made as the yacht was being brought in. "But really it is anyone’s guess. It is difficult to believe that this sort of thing can happen in this day and age.”

The Ramona, owned by Vagabond Cruises, was heading to the warm sunshine of the Caribbean to begin charter work. Reports said that an inquiry was to be held to investigate the cause of the tragedy.

THE SURVIVORS WERE identified as: Captain William Ross MacKay, 35, of Sunny Dale Avenue, Nova Scotia, Canada: Bernard Phylas Beaupre, 23, of Melrose Avenue, King City, Ontario: Mrs. Penny Gudgeon, 20, of Cedar Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia: Joel Dressel, 27, Oakley Drive, York. Pennsylvania: and Rosemond Harold, 22, Hospital Road. Castries, St. Lucia.

THE DEAD WERE identified as: Dr. Kenneth Ross MacIntyre, of Prince Edward Island, Canada: Crewmen Joseph Modeste, 32, of Grasilslet,[Gros Islet], St. Lucia: Louis Martin Deparest, 16: Thomas Simon,17: Rene Hendrickson, 24, all [three] of Castries, St. Lucia.

The yacht was out of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. MacKay said the [c]raft ran aground during the night. He said he fired flares to alert passing ships but none was in the area. A search began at daybreak. The yacht sank in relatively shallow water, and parts of the wreckage remained above the surface. Investigators said preliminary inquiries determined the yacht was operated by Vagabond Tours and had left Lunenburg on November 27, 1967.”

Adjourning the inquest until 2:15 p.m. later that day, Mr. Maddocks then told the nine-man jury that it was proper that it should be empaneled to deal with the matter – "as speedily and effectively as possible." Mr. Maddocks said he expected the jury would be able to begin hearing evidence that same afternoon. Mr. Anthony Palmer, Crown Counsel, assisted in the inquiry and told the court that it was believed that the owner had arrived in Bermuda, but this could not be confirmed. His name was given by one of the survivors as Mr. Boudreau.

The five deceased were named as Kenneth Ross MacIntyre, Joseph Modeste, Louis Martin Frances Departest, Rene Hendrickson and Winston Thomas Simon.

Superintendent of the Mariners Home, Mr. Caleb Wells, disclosed that the barquentine had been in difficulties for several days before she was finally wrecked on the reefs of the North Shore at the weekend. Club officials said they would not allow the press to speak to the survivors.

The Government were quick to issue a warning to ‘scavengers’ who were considering boarding the wrecked yacht. The Government quotes the 1898 Revenue Act in which it is stated that “all goods being derelict, flotsam, jetsam, or wreck being landed in these islands must be landed in the presence of a Customs Officer on duty or reported to such officer and all such goods not being landed in this manner are liable to be dealt with as goods illegally landed.”

"I have not got the full information yet,” he said. “I have one more thing to check out before I give my opinion on this business.”

The skipper of the Ramona, Mr. W. Ross MacKay and the remaining four survivors were staying at the Mariners Club under the care of superintendent Mr. Caleb Wells who said the five were still “shaken up after such a terrible experience.”

The proceedings of Marine Court of Inquiry had been delayed by about 30 minutes because of the non-arrival of the survivors. Television and Press cameramen awaiting their arrival outside the Colonial Secretariat thought that two of them had arrived when two men dressed in sea going clothes arrived at the court. After allowing themselves to be filmed entering and leaving the building, the men revealed that they were spectators who had come for the hearing “out of interest.”

ENGINEER

ENGINEER

At the opening of Wednesday’s shortened hearing Mr. C. A. Plumber, on behalf of the court, had outlined the facts which led up to the Marine Court of Inquiry.

He said: "On Monday the Coroner had opened his inquest on those who died. At the same time the police were taking statements from the survivors, and in view of the matters that became apparent from the statements it became clear that wider issues were involved than could not be covered by a Coroner’s terms of reference. It was therefore deemed necessary to inhibit the inquest and convene this court.”

"Copies of their statements have been given to the master of the vessel before this court began its investigations." He did not specify how many of the surviving crew-members had made the allegations. Mr. Plumber went on: “These allegations fall under two heads, drunkenness and incompetence as master; inattention to his duties, inattention to navigation and the safety of the ship.”

When asked by Mr. Barcilon if he had legal representation, Capt. MacKay replied: “I didn’t think that there was anything like this against me up to this point. I don’t know if I can be ready by tomorrow morning. I don’t know anyone in Bermuda, but I would like legal representation.”

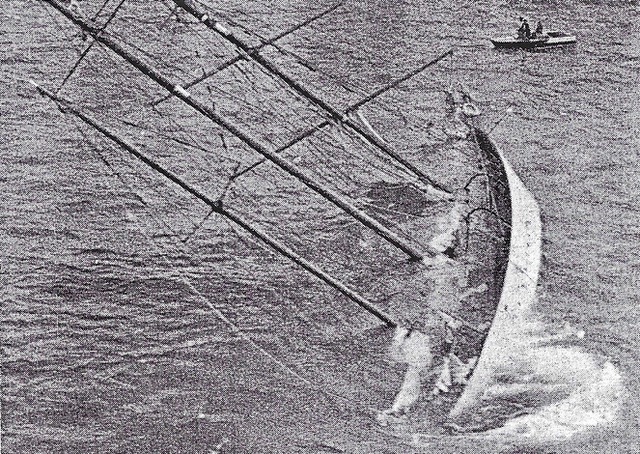

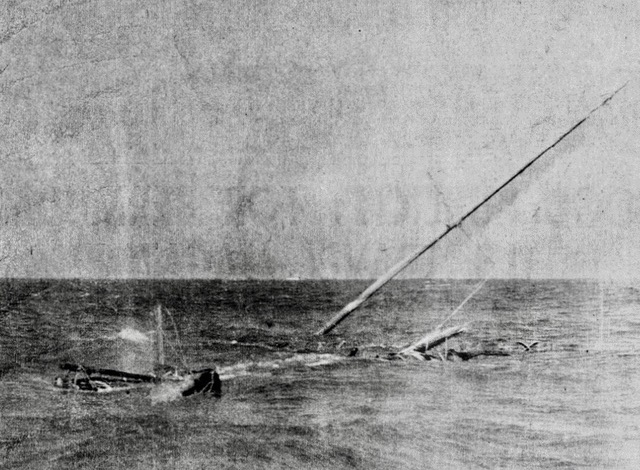

An update from a Harbour Radio spokesman advised that the Ramona had apparently slipped off the reef and was lying in about 40 feet of water. Her hull was submerged, but her masts were showing above the water.

Both had only been consulted after the captain had heard that allegations of "incompetence and drunkenness" had been made against him by survivors from the barquentine. In granting the adjournments the Hon. Mr. Justice Barcilon, chairman of the court, said: “I don’t think a matter of this gravity and importance should be rushed.”

Before adjourning however, the court appointed Mr. Martin Douglas Hutley, a member of the Marine and Ports Authority, as Marine Assessor. A Marine Assessor must be a man of some nautical experience. Besides assisting the court in its findings, he has an important part to play in the event of the court deciding to take action against any officer or the crew. The Marine Assessor must concur with any decision of the court regarding punitive action before that decision can be put into effect.

On Friday, December 8, the Bermuda Recorder reported that:–

Mr. Rosemond Harold was a St. Lucian national and that Capt. John S. Cowie was a retired Royal Naval Officer.

The proceedings were held in the Secretariat and were open to the public.

The Ramona, registered in the Bahamas, left Nova Scotia on November 27 bound for St. Lucia via Bermuda.

The Ramona hit the North Rock at about 8.30 pm [last Saturday night] but it wasn’t until some 12 hours later that people on the shore became aware of the tragedy. In the meantime, the ship’s doctor Dr. Kenneth Ross MacIntyre of Prince Edward Island and four teenaged seamen from St. Lucia had lost their lives. The survivors were found in a flooded dinghy suffering from exposure and shock.

The fifth man who lost his life was a Canadian, Dr. Kenneth Ross MacIntyre, whose body was returned to Canada. A memorial at the Community Park Cemetery, Kings County, Prince Edward Island, Canada bears his name and date of birth.

Following the funeral, boats had set out for the wreck of the Ramona to study the possibility of salvaging the 120-foot steel-hulled barquentine. Four separate interests were involved. The Bermuda Police went out in Mr. Harry Cox’s ‘Shearwater’’ to carry out certain investigations for the court of inquiry, and aboard Mr. Eldon Simons’ boat ‘Sea Bob’ were representatives of the owners of the yacht, Harnett and Richardson which represents Lloyd, and the Ports Authority.

Both Mr. Boudreau and Mr. Eldon Simons of the Fibre Glass and Body Shop at Darrell's Island had commented on the striking sight presented by the tall masts of the vessel sticking up through the water. Her decks could be seen just below the surface and the water was so clear and calm that the whole hull could be seen through the water.

About six divers, some using underwater cameras, had made a study of the yacht's condition. Mr. Simons had noted that considering the possibility that good weather might not last long, any salvage work would probably have to be done as quickly as possible. He thought that probably special rubber floatation bags might have to be flown here from the United States for the job.

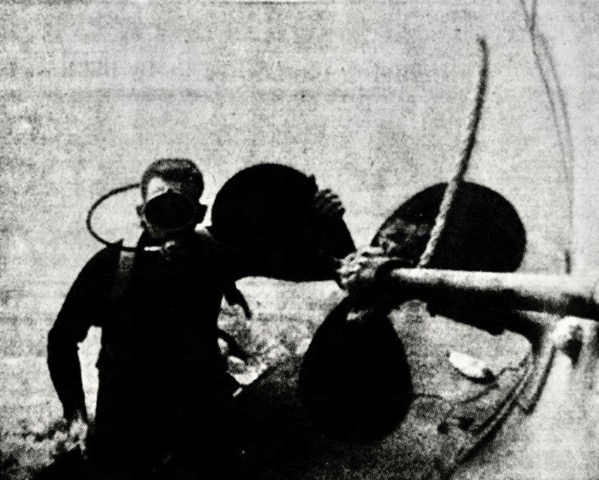

A number of items were salvaged from the yacht and will be temporarily stored at Darrell’s Island. These included one of the vessel’s sextants, a wheel (not the main wheel), a number of papers and other items. Also towed ashore by the ‘Sea Bob’ were two gaffs and a boom and a team of divers and surveyors were planning to go out to the yacht again in the days ahead.

One of the yacht Ramona’s sextants is examined after being brought to shore

One of the yacht Ramona’s sextants is examined after being brought to shore

But an all-important factor was the weather. “It certainly depends on how long a spell of good weather we get,” added Mr. Parker. He noted that the barometer the previous night was about a tenth of a degree above 30, and was still steady.

Other questions involved in deciding whether to salvage the vessel were the cost of the operation and the damage already sustained by the yacht. Mr. Parker said he would be calling the New York office of London Salvage, the company insuring the yacht, to see what they want to do. "Probably we will know then what we will do. We would certainly have to get in some special equipment,” he remarked, adding that during the survey work they had just completed, measurements had been taken of the yacht's compartments to determine the size of the special rubber flotation bags that would have to be brought here, installed and then pumped full of air to bring the vessel to the surface.

"If we are fortunate enough to raise her, I don’t think there will be too much trouble getting her to a clear channel,” said Mr. Parker, adding, "I don’t think it would take too long, depending on the weather. She is in a place where we can get to her quite easily.”

Besides the floatation bags, about all that would be needed would be several small boats with pumps and air compressors on board; there is adequate water for such boats in the area.

Mr. Cox’s crew were attempting to find the yacht’s log book, “But that’s a hard thing to find,” said Mr. Parker. The divers from the ‘Sea Bob’ found some other and less important papers, all in poor condition. “We even found some outside and under the keel,” he said, adding that the divers had even found a child’s arithmetic book.

When asked if there were any legal questions involving the salvage of the yacht, Mr. Parker said he was not a legal expert but added, “I wouldn't think there are any legal problems. She is just a stranded yacht. In my view she still belongs to the owners and the underwriters.”

RG Tuesday, December 12, 1967

Captain Boudreau said in evidence that Vagabond Cruises had acquired the Ramona in 1964 or 1965. She was a steel-hulled yacht, 116 feet in length and 24 feet in beam, drawing 15 feet, and weighing 126 tons. She was powered by a 200 hp diesel engine, in addition to her total of eight sails, including storm-sail.

[Of note here is that Ramona was powered by one diesel engine only, which is contrary to a report in a publication elsewhere that she was powered by two diesel engines].

Asked Mr. Palmer: “Were any of Capt. MacKay’s requests for purchases relative to the safety of the ship refused by you?” — “No.”

He told the Court that it was the policy of his company not to allow crewmen to have liquor on board. Before the ship left port, he had removed liquor that was on board, leaving only a half bottle of rum for medicinal purposes. "Knowing Joel Dressel, I felt confident that he would carry on the regulations of our company, and he and Capt. MacKay were on terms of cooperation,” the witness continued. He said that Mr. Dressel, who sailed on the Ramona as mate, had worked himself up to a position of responsibility with Vagabond Cruises, and was a minor shareholder.

Speaking of the attitude to drinks on the ship, Capt. Boudreau said that shortly before the departure of the Ramona [some] crewmen had approached the captain to ask him about securing bonded stores. "Capt. MacKay came to me and said that this was not a good idea. I agreed with him and told him that I had no intention of permitting any liquor at all.”

Questioned by the Hon. Mr. Justice Barcilon, Capt. Boudreau said that there was "absolutely no need for a fathometer.” He further said that the Ramona’s boats could hold a total of about 20 people.

After describing, with the aid of a diagram, the layout of the Ramona, Capt. MacKay told the story of the voyage.

In addition, most of the crew were seasick, and unable to help. "I did not deem it prudent to bring the ship round in those mountainous seas and ride it out. I decided to let the ship run before the wind. I knew before leaving Lunenburg that it was likely that I would run into some bad weather, and I had decided in my own mind to call at Bermuda for any repairs. It was my intention to call at St. George’s as our stay would be as brief as possible,’’ the captain stated. He said that because of the state of the crew only he, Mr. Dressel and occasionally Dr. Kenneth MacIntyre who was due to leave the ship at Bermuda but died in the tragedy, were able to take turns at the wheel.

"At some time on the Thursday I had gone down into the ship to check out damage. When I came down the forward hatch a member of the crew was standing with his lifejacket on. I was happy to see him up on his feet, but as I went aft some other crew members were getting on their lifejackets. I asked them what was going on, or something to that effect. Rene Hendrickson (another of the victims) said that the skipper said for them to get their lifejackets on because we were sinking,” said Capt. MacKay. "I told them that I had not ordered it, and there was nothing wrong with the ship.”

Questioned by Mr. Palmer, he explained that the crewmen sometimes referred to Mr. Dressel as the skipper, and to himself as captain. He went on: "On Friday the weather moderated, although the seas were still high. The radar wire had been ripped down during Thursday. It was torn adrift from aloft, and I would not go up myself or send anyone else up there.”

"I thought I would be further east, but I didn’t think I was too far out. We had been crossing the Gulf Stream which would have carried us east. I was also further south than I had anticipated, as the ship was apparently making a better speed. At that point it was clear to me that I would not make Bermuda in daylight.” For this reason, said Capt. MacKay, he decided to go east of Bermuda and lay up in the lee of the islands.

“If I had gone west, I would have had about 17 miles of shoal to contend with. The other way I had two or three miles. The wind was north by east, at about 30 knots,” he said in reply to Mr. Palmer.

"Dr. MacIntyre was at the wheel when we changed course. I was very concerned. I knew that I was going to be driven into the reef unless I could get more power. I called for more power, but they told me that was it. I believe that Dressel said to me that she was airlocked. That would mean an air lock in the fuel system."

He continued:

"I saw the breakers. The first ones I saw were on my port quarter. I still had clear water otherwise. Mr. Dressel was around the engine room. I had asked him to go and bust the governors off the engine. Then I hit, lightly. I was headed out to sea, and the next sea was able to carry her up and over the reef. I was mainly concerned to keep the ship from rolling over at this point. I gave the order for everyone to get on deck with their lifejackets.”

Capt. MacKay, who was still in some pain from the injuries he received in the shipwreck, said that he called for the main lifeboat to be lowered, but due to storm damage it could not be moved. He went below and collected a gun and ammunition, to sound an alarm, some papers and some flares. In all, he said, five parachute flares were tried, but failed to work properly. The gun was thrown overboard.

"The crew began jumping into the water, with no order from me to abandon ship. I said stay with the ship. All the crew left the ship except me, then I left the ship myself.”

Mr. Palmer: "Did the fact that you can’t swim have anything to do with your leaving the ship when you had advised the others against it?” — “Yes, I suppose it did. But I wanted to keep the crew together.”

Capt. MacKay told the court that before the crew left, the ship had taken on a list of about 35 degrees, and a dinghy and a dory had been launched. He said that he jumped into the water, and climbed into the dory, which had four people in it. The dory and the dinghy were tied together, and the dory eventually became waterlogged and overturned. It was righted again, but with six or seven of them in it, the dory remained swamped. Dr. MacIntyre and Mr. Beaupre were in the water clinging to the dinghy.

Capt. MacKay said that his lifejacket did not make him float. “I went down. I grabbed hold of someone, and then realized that they were going down with me, so I let go. Finally, Beaupre grabbed me by the hair, and held me above water.” Eventually, he said, the two boats became parted, with the main group in the dory. MacKay said that he was in the back of the little boat, trying to balance it. Mr. Hendrickson was the first to go, he said. The man went over the side, and was clinging to the boat. They tried to get him but without success.

Then Winston Thomas Simons started to fall asleep and eventually drowned.

Capt. MacKay said that he thought that Louis Depareste had jumped into the water, although because he was facing backwards, he could not see much of what happened.

The other St. Lucian victim, Joseph Modeste, was the last to die.

“Joseph had been doing some paddling,” said Capt. MacKay in a voice strained with emotion. "Then he stopped. He wanted to go with the rest. He said something, and he and Harold [Rosemond Harold, a survivor] spoke to each other in their own language. He came up close to me, and put his hands on my shoulders.

I said, “That’s right, Joseph. You hang on to me and I’ll hang on to the boat. Don’t go with the rest. It seemed to help him. Later I turned and saw him. His eyes looked glassy and sightless. He suddenly let go of me and fell back into the boat.” Capt. MacKay said that before this Joseph had been going out of the boat, although Harold had tried to stop him.

Capt. MacKay said that he felt he had acted calmly and in a clear-thinking way at the time of the disaster. He wanted to keep the crew together, and tried to use the flares and warning equipment to the best of his ability.

Mr. Barcilon asked him: “What instructions did you receive about drinking?”

He replied, “I was given no instructions,” but added: “I don’t allow liquor in my ships."

He also told the court that he had only had one night’s sleep since the journey started. The rest of the time he had hardly eaten or slept.”

“If you had known that a length of line was around the propeller shaft would you have come to the conclusion that that accounted for the loss of power?”

The engineer replied: "Yes, it sure would.”

At the opening of his evidence Mr. Beaupre, who gave his evidence all afternoon, said that he had been a sailor for about 30 months. He told of the death of Dr. Kenneth Ross MacIntyre, whose body had been flown back to Canada last week. He said that after the yacht had hit the reef and had been abandoned, he and Dr. MacIntyre tried to reach land by propelling a small dinghy with their feet through the water.

Earlier, the court heard, Mr. Beaupre cut the line connecting the dinghy with the rest of the crew in a dory. The dinghy was eventually abandoned, and Dr. MacIntyre set off for land, swimming.

"He didn’t say anything, he just left.” said Mr. Beaupre. I had suggested waiting for daybreak, so that we could get a better concept of the distance. But he said he thought he could make it.

He went on: “I’m sure I passed out. I have no memory of what happened until I came to and it was daylight. Dr. MacIntyre was on my back, and I gave him a shot of air, mouth to mouth. He looked to be in a rough shape.”

Mr. Beaupre said that just before he tried the kiss of life, Dr. MacIntyre gave a small sigh, and his eyes opened briefly. He died shortly afterwards, still on the man’s back.

"I had to leave him. The next thing I remember is being in the boat which picked me up, and then waking up in hospital."

On the Saturday that the Ramona struck the reef, he said, he had stood the 4 to 8 a.m. watch at the wheel, and then went to bed, getting up at about midday. The weather was then still "nasty” with heavy seas, although the wind had subsided. That afternoon the crew were told that the vessel was only 35 miles off Bermuda, and there was a “sing-song” with some of them “hopping around in bare feet.”

He told the Court that he went on deck, but later returned to the engine room. Later, Louis Depareste [victim] came down and told him that more power was needed from the engine.

“I increased the engine to maximum by opening the throttles, but it had no effect. The revolution counter stayed where it was. I took the throttle linkage out and turned the engine to maximum by hand, but it still had no effect, according to the rev. counter.”

At this point Mr. Palmer mentioned the question of a line around the shaft. He also asked if the engine had been functioning normally prior to the emergency. Mr. Beaupre said that it had, but had only been in use at the cruising power of 1200 rpm. “While I was in the engine room, I felt the boat strike. Mr. Dressel [the mate, survivor] called to me through the hatch and I went up on deck. I had a life jacket.”

“It was chaotic”, said Mr. Beaupre. “The West Indians were standing talking in their own tongue. The other people were standing around. Dr. MacIntyre had a lighted flare in his hand. The vessel was listing to port, around 12 to 15 degrees, I’m really not sure.”

He said that surf was breaking over the boat, and he timed the waves and shouted warnings to the crew each time a wave was due. He told them to keep to the starboard side of the ship, and he protected Mrs. Penny Gudgeon [survivor] by huddling over her.

Mr. Palmer asked, “Did you see what the captain was doing at this time?”

“If I remember right, he was back at the wheel. I told Louis to get buckets for bailing, and told Winston Simon [victim] to look after the oars. I also told Rosemond Harold [survivor] to make sure the plugs were in the dory. These instructions were carried out. Rosemond made temporary plugs out of tarpaulin. One of the plugs was not in the dory. I gave instructions to Louis about fresh water.”

“Did you give them because you heard no-one else give them?” – “I don’t know why I gave them.”

Continuing with his story, Mr. Beaupre said that most of the crew were trying to launch the lifeboat, but were unsuccessful because of a broken ring-bolt. He and Captain MacKay tried to send up parachute flares. One burned his leg, but his second went up successfully, well above mast height. A flare launched by Capt. MacKay did not go up, but travelled horizontally over the water.

Mr. Beaupre said he thought he was the last to leave the stricken Ramona. When he jumped into the water he jumped between the dory and the dinghy, and held the two together, while someone lashed them together.

Asked by Mr. Palmer if he would say that Capt. MacKay was in “bad shape” he replied, “I would say so.”

“I swam between the skiff and the dory for a while,” Mr. Beaupre went on.

“Dr. MacIntyre, who was in the water beside the skiff, suggested we cut the line and make it for the shore. I didn't think it was the right thing to do. I told him to keep up his morale, that I thought the land was only about five miles away, although I thought it was further. Dr. MacIntyre thought it was nearer than five miles.”

He said that eventually he shouted across to the dory, which contained the other eight crew members, to tell them that they should cut the line and try to make the shore. Someone replied “O.K.,” he said.

In reply to a question from Mr. Francis Daly, for the Government, Mr. Beaupre said that visibility was good at the time the flare went up.

In re-examination, Mr. Palmer asked, “Before you abandoned the Ramona did you hear any of the survivors say anything about the captain drinking?” – “No.”

“While you were swimming between the dory and the dinghy, was there a state of panic among the people in the dory? – “I would not call it panic necessarily, it was disbelief, and shock.”

“Any comments on his conduct after the Ramona had been abandoned?” – “No.”

Mr. Beaupre was asked by the Hon. Mr. Justice Barcilon, if he thought an air lock in the fuel system could be responsible for the loss of power. He replied that it could have been an air lock, but it was “highly unlikely” that one would have occurred.

Further to his comment on the state of the crew immediately after the shipwreck, he said that the West Indians appeared to be almost in a state of panic.

After the hearing Mr. Guy Boudreau, president of Vagabond Cruises, Ltd., owners of the Ramona, said that insurance underwriters were at present investigating the possibilities of salvage. “It will be a few days before we know for sure what can be done,” he said.

The court heard from two witnesses that the captain of the doomed yacht Ramona had been drinking before the vessel grounded on the killer North reefs. The charges were made by the vessel’s first mate, and her former skipper, Joel Edward Dressel, and West Indian deck hand Rosemond Harold.

Mr. Dressel also backed up his previous statement to local police when he repeated that had Captain Ross MacKay “put more into his job this disaster would never have happened.” The court was also told how the four other West Indian crewmembers had abandoned the Ramona’s dory after the boat was drifting inland inside Bermuda’s reefs – and they had died.

Mr. Dressel told the court that a representative of the Ramona’s owner, Captain Walter Boudreau, had decided that Capt. William Ross MacKay, a master mariner, should take the yacht from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia to the West Indies and that before the voyage he had offered Captain MacKay a drink of rum which he had refused saying that he only drank beer. After leaving Lunenburg, Mr. Dressel said, the Ramona hit a heavy blow on the Thursday, and by Friday the “winds were well over hurricane force and the seas were mountainous.” By Saturday, he said, the wind had reduced to about force six with 25 to 30 feet seas.

It was on Friday at about midnight, he went on, that the captain told him that he had tried to radio Boston for a weather forecast and had failed to get through because he thought the radio was dead.

Mr. Dressel said Capt. MacKay’s voice was “a bit slurred,” and added: "I thought he had been drinking.” Mr. Dressel explained that he had been on the deck of the Ramona from 10 p.m. on Thursday until 1.0 a.m. on Saturday and said that during that time the captain had appeared on the deck only periodically. “It seemed to me that he was below more than he was on deck. He only came up for short periods,” he stated.

“Mrs. Gudgeon's bottle was not there,” he went on, “and Bernie (Beaupre), who had a bottle of rum, offered him some and he took a drink.”

Mr. Dressel said that the captain poured himself more than half a tumbler of rum and he saw him drink “some of it."

At about 6.10 p.m. that evening lights were sighted and Mr. Dressel said he thought that they could have been either North Rock light or St. David’s light. Mr. Dressel suggested that the square sail should be lowered. Captain MacKay tried to help them with the task, even though he told him that he thought the Ramona was on a dangerous course and to get it back on a proper one. Later the Captain agreed to start the engine and one of the crew took the wheel when the captain went below.

Mr. Dressel said that no more power came from the engine because, as he thought then, there was an air lock in the system or trouble with the engine’s governor. He added that by now he had seen at the wreck a length of rope wrapped around the propellor shaft of the ship and this, he said, had come from the Ramona and would cause friction and drag on the propellor.

He said that two flares were fired. One reached only as high as the masthead and the other shot straight outwards and landed in the sea as soon as its parachute opened.

That night one of the West Indian crew, Mr. Louis Depareste, told Mr. Dressel: “I will do a deal.” And later, he said: “Skipper, I will go and let you get ashore.”

Mr. Depareste then went into the water but, Mr. Dressel said, he managed to pull him back into the dory but the crewman only left the boat again and disappeared.

In the night two others, Mr. Hendrickson Rene (sic) and Mr. Winston Simon, also left the boat. With daylight the fourth West Indian, Mr. Joseph Modeste, who was the second mate, tried to leave the boat, but was pulled back two or three times, before he eventually left altogether after unfastening his lifejacket.

Asked his general impression of Captain MacKay’s command of the Ramona, Mr. Dressel told the court: "I thought he was too lax in his attitude towards everything in this storm and approaching Bermuda. I expected him to be more nervous than he was and remain on deck more.”

Twice on the voyage, Mr. Dressel said, – on Friday night and when he helped take down the sail on Saturday, – he formed the impression that the captain was drunk. He also confirmed a statement which he made to local police in which he stated: “If he had put more into his job this disaster would never have happened.”

On Saturday at about 6.0 p.m., he maintained that he saw Captain MacKay drinking a glass of rum in the galley of the vessel. He added that during the hurricane he formed the impression the captain was so drunk that he could not keep a straight course at the wheel and appeared unsteady later when walking about below.

He said that by this he gathered that Mr. Modeste wanted him to jump in the sea with him. He grabbed the second mate and pulled him back into the boat and this happened some five times until, on the fifth occasion, Mr. Modeste tried to drag him into the water. He pushed him off and Mr. Modeste sank out of sight.

A deadly hush settled over the court as Mr. Palmer stated that he had a cable from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Halifax. He asked Captain MacKay if in July, 1961, he had been convicted on a charge of impaired driving. The latter admitted he had.

Mr. Palmer asked Captain MacKay if he had been convicted on a charge of intoxication under the Liquor Control Act in 1966. The captain also agreed to this.

The court counsel then asked if on November 15 this year, less than two weeks before the Ramona sailed from Lunenburg. Nova Scotia, he had been arrested and charged with impaired driving, and if he was at present on bail in respect of that charge in the amount of $2,000. “No. $500," Captain MacKay replied.

“And this is the gentleman who saved your life, is he not?” asked Mr. Palmer, after referring to Mr. Beaupre having come to the aid of the master in the sea and lifting his head out of the water, since Captain MacKay could not swim.

“Yes,” replied the captain quietly.

The first witness of the day was Mr. Rosemond Harold, the St. Lucian deckhand, who had given the first part of his testimony on Wednesday.

Replying to a question put by Mr. E. W. P. Vesey, M.C.P., appearing for the owners of the yacht, Vagabond Cruises, he said, “I don’t drink at sea,” adding that this was the policy of the company. He said he had seen the captain drinking a can of beer and a glass of rum during the trip.

Replying to Mr. Nicholas Dill, for Captain MacKay, Mr. Harold said he thought the master was drunk and unsteady on his feet. He also maintained Captain MacKay had said “abandon ship”, which caused Mr. Dill to remark: “You are the only who has said that.”

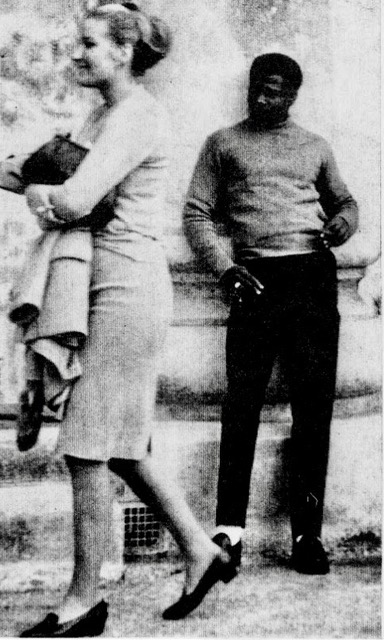

She maintained the captain did not appear sober at about 6 p.m. on Saturday, December 2, approximately 2 hours before the Ramona was abandoned on the reefs on the North Rock. Wearing a smart black suit with black velvet trimmings with her long blonde hair drawn back over the nape of her neck, Mrs. Gudgeon said she found “there was a lot of confusion” when she went on deck after the yacht had struck the reefs.

“No, Mr. Dressel seemed to be in charge,” she replied, referring to the first mate Mr. Joel Dressel, who had been master of the Ramona for the last four years but who is not a master mariner.

She recalled Mr. Beaupre, Mr. Dressel and Dr. Kenneth MacIntyre [one of the five who drowned] were getting the boats ready in case they were needed.

“The captain came back from the wheelhouse and said, “What are you getting the boats ready for? Don’t leave the ship.” “I think he was very afraid,” said Mrs. Gudgeon.

She alleged that as she was getting into the dory which was in the water she thought she heard Mr. Joseph Modeste [another of the five victims] saying ‘abandon ship’, but Captain Mackay was saying, ‘Don’t leave me.’

Later the captain also got into the dory. After the dory capsized several times and was eventually righted, eight of them got into it, while Dr. MacIntyre and Mr. Beaupre, both Canadians, were alone in a skiff.

“I remember the strong smell of liquor,” replied Mrs. Gudgeon.

“Do you feel any person was in command of the dory?”

“Yes, definitely Mr. Dressel,” was her reply.

She did not see Winston and Hendrickson leave the dory, she told her lawyer Mr. Robert Motyer, – “but I heard [Winston] Simon give a moaning scream several times. He must have been quite close.”

She repeated what the other witnesses had said – how they had all tried to stop the three Saint Lucians from going into the water, – “but I don’t think there was anything any of us could have done,” she said.

Referring to the other two Saint Lucians, the deckhands Mr. Harold and Mr. Modeste, Mrs. Gudgeon remarked: “They were completely in control, but by daylight and shortly before the first rescue boat arrived, Mr. Modeste was attempting to get out of the boat repeatedly, and became quite violent. In the end, he went over the side and disappeared.”

Mr. Dill asked how the master looked on the Saturday afternoon. “He always seemed so happy and joking,” she said.

“Would you say he was drunk?”

“I wouldn’t say he was feeling any pain.”

“How do you come to that conclusion?” asked Mr. Dill.

“His general attitude and bearing.” This reminded her of the way Captain Mackay always crossed the wardroom from the galley. “He would count the waves, and after three he would consider it would be calm, and then he would tippy-toe across the wardroom. I used to like to watch him,” she remarked, causing amusement.

Mr. Harry Cox, local skin diver, identified a half bottle of rum, which he said had floated up from the Ramona on Friday, December 8. He said he found no ship’s log or papers bearing on the tragedy.

Det. Sgt. John “Sean” Sheehan identified one unopened bottle of white rum found on board last Friday.

He said it was his firm belief the Ramona “was driven in by sea and winds,” and insisted he had kept a log and made entries every hour, or during the bad weather periods, every four hours.

“Did you give an order to abandon ship?” asked Mr. Dill.

“No,” was the reply.

Cross-examining, Mr. Palmer asked what he had to say about Mrs. Gudgeon’s evidence. The captain said she was deliberately lying and, when asked what reason she could have, he said: “It could be some of my strictness in the ship. And she was interested in one of the part-owners (Mr. Dressel), but these are things I can only surmise.”

The captain could give no reason why Mr. Beaupre and Mr. Harold would have said they had seen him drinking, but maintained they were also lying.

“No, I don't have a drinking problem. I have a bad stomach.”

“Do you know it was dangerous for you to have one drink, which leads to another drink, and another?”

Captain MacKay did not give any concrete answer.

Mr. Palmer then referred to the cable from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and after reading the previous charges, asked if Captain MacKay had been demoted from mate on the ‘Bounty’ to navigator?

“No, I later became her master,” claimed the captain.

“Do you consider yourself to have a drinking problem?”

“No.”

“Do you consider yourself to be an alcoholic?”

“No.”

“Anyone who thought you were would be mistaken?” asked Mr. Palmer.

“Yes.”

The Hon. Mr. Justice Barcilon, asked if he was suggesting that because Mr. Dressel was part owner and former master he wanted him off the ship.

“Yes,” replied Captain MacKay.

“And the suggestion is that Mrs. Gudgeon, being friendly with him . . . has gone into this conspiracy?”

“Yes.”

Captain W. G. Boudreau, representing the yacht’s owners, was recalled by Mr. Palmer and questioned on the inquiries made about Captain MacKay before engaging him as master.

Captain Boudreau said he had made verbal enquiries from three captains in Canada, including the master of the schooner ‘Bluenose II’, and had checked the master’s references and documents.

“Were you completely satisfied?”

“I received no adverse opinion,” he replied.

“Did you have any reason to believe Captain MacKay was a drinker as a result of your inquiries?”

“No.”

The witness agreed these inquiries must have taken place after November 15, when Captain MacKay was arrested for impaired driving.

Captain Boudreau added he was satisfied after the investigation he had made that – “Captain MacKay was completely capable of taking the Ramona down to Bermuda. I had no reservations whatsoever.”

Asked if any salvage attempt would be made, he added: "We are still hopeful.”

Meanwhile, the Bermuda Recorder of Friday, December 15, 1967 reported that a week of sensational testimony by five survivors of the wrecked yacht Ramona had reached a climax when the master of the ship captain William Ross MacKay, 36, of Nova Scotia was recalled before the marine court of enquiry. The captain was asked for his reaction to accusations by three of the survivors that he was drunk and incapable when the ship ran aground with the loss of five lives. Captain MacKay said his accusers were lying.

And when asked by the Crown counsel if he had a drinking problem and was an alcoholic the captain had replied no, – but then his face flushed heavily.

Mr. Nicholas B. Dill, appearing for Captain MacKay, told the court that as a result of the earlier evidence when it was made known that Captain Mackay was on bail for impaired driving and had previous drinking charges against him, he “had made a call to the United States for an additional witness in respect of his client’s character. I don’t know whether he will be able to come.”

Mr. Dill informed the court president, the Hon. Mr. Justice Barcilon, that the witness – if he could come to Bermuda – would be here in time for Monday morning, when the court resumes.

During the hearing, the court also heard from Mr. John Ellison, whose Cessna aircraft helped in the air sea rescue operation on December 3. Mr. Ellison criticized the lack of coordination in the search and he emphasized the need for grid maps which would specify where each boat would go, rather than having them go in unspecified directions.

The first witness of the day was Police Constable Derek Singleton, who was duty officer at Operations in Prospect on Sunday morning, December 3. He received a telephone call at 7.45 a.m. that a yacht had struck the reefs at North Rock, and he telephoned Harbour Radio.

Constable Derek Singleton

Constable Derek SingletonThe next witness, Mr. Musson Wainwright, owner of Tugboat Annie, told the court that he was informed about the Ramona at about 8 a.m. on December 3, although it was not at that time known if there were any survivors. He approached the yacht from downwind, since he thought anything off the boat would come in that direction.

Asked by Mr. Anthony Palmer, Crown Counsel for the court, if the Saint Lucians were dead, Mr. Wainwright replied: "Yes, their heads were down in the water. They wore life jackets, which were supporting them.” After proceeding at full speed, without picking up the dead men, – “I came across a survivor in his life jacket.” said Mr. Wainwright. [This was the Canadian engineer, Mr. Bernard Beaupre.]

“Was he in any condition when you picked him up to inform you about the wreck?” asked Mr. Palmer. The witness said he was not, and he had been wrapped in warm clothing once in the boat. They took him ashore to St. George’s and it was not until he was being put in the ambulance that Mr. Beaupre was able to say how many people were aboard the Ramona.

Mr. Dill: “When you arrived there can you say anything about the attitude of the captain?”

“When I came alongside,” Mr. Wainwright replied, “everybody was well behaved, sitting very tight, arms each side holding the boat upright.”

He ordered all of them aboard his boat, and personally helped Captain Mackay aboard.

“Did you smell anything on him?” asked Mr. Dill, referring to the evidence of Mrs. Penny Gudgeon, one of the survivors charging Captain MacKay with drunkenness and incompetence, who on Thursday had said his breath smelled of liquor in the dory.

“I did not,” Mr. Wainwright answered, adding he thought he would have been able to smell the captain’s breath, since in the process of helping him aboard Tugboat Annie, the two men had necessarily had their faces close together.

Asked how the sea was at that time, the witness said: "There were conditions I had never seen before. Surge and tide were all the way in, the tide was very strong out of the north.”

Asked by Mr. Palmer if he had any comments to make on the way the search itself was carried out, Mr. Ellison replied: “That is difficult from the point of view of someone in the air, but one did have the feeling a more coordinated search could have been made if each of the boats had had specific areas to search, rather than being in one block with no one knowing quite where they were searching.”

He emphasized the importance of grid search maps being available, so that each boatman could be assigned a specific area to search. Mr. Ellison said he saw from his plane an upturned dinghy, with no one in the vicinity. This was the one used by Mr. Beaupre, and his friend Dr. Kenneth MacIntyre of Canada, who drowned in the tragedy.

Mr. Daly pointed out between 15 and 20 boats assisted in the search – “so the area was getting pretty good coverage, even though it was not well organized?” Pointing out there was no official flight pattern for the searching aircraft or map references, Mr. Ellison said: "I suppose if blue bottle flies were in a bottle long enough, they would fly through all the space.”

Mr. James A. Pearman, chairman of the committee appointed by the Marine Board to make a report on the advisability of establishing an Air Sea Rescue operation in Bermuda, said he was informed about the wreck at about 8:50 a.m. on December 3.

"Are there any standing instructions drawn up with regard to putting air-sea rescue into operation?” inquired Mr. Palmer. “There are no standing instructions as such,” was the answer. Mr. Pearman explained there was a committee, including representatives of the Marine Board and Fort George, and the voluntary services of the United States Air Force, the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Navy were available as they were needed.

"Harbour Radio,” replied Mr. Pearman.

Mr. Palmer asked: “It is not part of your function as chairman of this committee? — “No.”

Questioned further, Mr. Pearman said the Police volunteered their services on land, and also assisted with their motor launch if it were available.

Several boat owners made their vessels available, and the owners of four private aircraft also assisted when they could.

Have you made any recommendations regarding a search map?” asked Mr. Palmer.

Mr. Pearman: "Not to any official body, no.”

Mr. Palmer: “Would you wish to make any recommendations?”

Mr. Pearman: “Yes, I think that this would be an advisable thing to have for all boat owners, aircraft, and certainly would facilitate the restriction of one’s whereabouts.”

Answering Mr. Barcilon, he explained the procedure which is now followed when a search is launched. He added: “I think the committee need to go into the question of facilities further, and would like to make recommendations to Government in respect to certain facilities which we think we need.”

He told Mr. Daly the committee members were all volunteers who had been asked by the Marine Board to assist in air-sea rescue when necessary. They were not an official organization.

Witness Lt. Col. Paul W. Rudlop of Kindley Air Force Base, who was operations officer and acting commander of the base on December 3, told the court the base received a call concerning the Ramona at 9.45 a.m. that day from the St. George’s Police Station. A rescue aircraft was airborne 12 minutes later and reached the wreck at about 10 a.m.

He informed Mr. Daly: “We will respond to any emergency.”

“You don’t have to go through a local procedure?” asked Mr. Daly.

“That is right,” replied the colonel.

The court was told that two helicopters had also been called in – one was the United States Navy helicopter based at Kindley, and the other was an R.C.N. Sea King helicopter from the Canadian aircraft carrier ‘Bonaventure’ which was nearby the island at the time.

Mr. Salter said he did not like to request Kindley’s help until sufficient facts were known to put before them. He agreed there had been some confusion as to the number of people in the water, since it was first assumed that Mr. Wainwright had picked up the two drowned Saint Lucians he had seen in the water. But for this, there would have been no confusion, he remarked.

"That was a mistake,” he said, since he sighted the yacht two miles east of the rock, and accordingly changed course. He reached her about the same time as the ‘Wally III’, owned by Mr. Roy Taylor.

The ‘Blue Heron’ went downwind, where they recovered the body of a West Indian from the water.

“The body was upright, but completely submerged, and the life jacket was behind his head. The top strap was in place, but the bottom ones had the strings hanging down,” said Constable Garland.

Questioned by Mr. E. W. P. Vesey, M.C.P., for the owners of the Ramona – Vagabond Cruises – PC Garland said he learned the drowned man’s name was Mr. Joseph Modeste. The policeman said he would have taken another, quicker course to the Ramona, if he had known she was east of North Rock. Mr. Vesey pointed out – after noting which course the policeman would have taken – that this would have brought the ‘Blue Heron’ to where the five survivors were in the dory.

Blue Heron

Blue Heron

CLICK HERE: to read an excellent article about the building of Bermuda’s first police boat the Blue Heron.

“This information you had, originated from Police Headquarters?”

“Yes,” agreed Constable Garland.

Contrary to reports circulating at the time, the Ramona actually floundered on the rim reef 1¼ miles (2.01168 kilometers) to the east of the North Rock Beacon. She hit the bar at a point between the North Rock Beacon and the North East Breakers more locally known among fishermen of the day as the North East Pointers – about 7-8 miles out from the mainland at (GPS 32.47955 – 64.7652).

It was Dressel’s contention that MacKay had misread the North Rock Beacon for the N.E. Buoy light and steamed Ramona right into the reef line. When MacKay spotted the breakers, he attempted to turn the boat out to seaward but, with her limited power, she hit the breakers before he could clear them. Dressel was in the engine room at the time of impact as the boat was not exhibiting its usual performance. I found a heavy rope wrapped around her prop when I first dove on her which had probably washed off the deck in the heavy weather they were experiencing and fouled the prop. The North East buoy has since been replaced with a fixed beacon on the reef-line.

I’ve heard the term N.E. Pointers all my life and always assumed it was the shallow area North of N.E. Breakers. There is no “point” as the 10-fathom line is curved in this area. The fishing fraternity refer to the area to the N.W. of North Rock that sticks out, again in a long curve, as “Long Point” – but there is no “point”. Other popular fishing spots like Peter Riley’s, Sally Tucker’s, The Short Course, The Hind Grounds, etc. you will not find on a chart and many amateur fishermen may never have heard of them. I have been fishing offshore and the Banks since I was 12 years old but still don’t know everything.

Ramona came across the Great Breaker Ledge Flat one and a quarter miles to the east of North Rock Beacon. This would place her grounding approximately a third of the way along the breaker ledge and east of what could be [referred to as the] N.E. Pointers.”

Having heard on his radio – which picks up Harbour Radio’s conversations with boat captains – that there were 10 people aboard, he telephoned Harbour Radio and gave them his own position and bearing, after which he saw Mr. Wainwright’s boat heading towards the dory.

“The cause of death in all cases was drowning,” he said.

“Was there an additional cause?” asked Mr. Palmer.

“In one of the coloured persons – Joseph Modeste,” replied the pathologist. “He had suffered a congenital abnormality in his blood.”

“Was that a fatal disease in itself?”

“No.” answered Dr. Wickham.

Witness Mr. Dickinson of St. George’s said he went fishing at about 6 a.m. on December 3. His boat was just to the east of North Rock “when I saw something sticking up, like a spar,” he recalled. “It startled me, and I headed straight back to St. George’s.” With the aid of his nephew’s spy-glass he made out the wreck, and telephoned the Police.

Mr. Nicholas Dill, attorney for Captain William Ross MacKay, had called the man to testify as to the character of the captain who had been accused of drunkenness and incompetence by some of the Ramona survivors. Mr. Dill met the surprise witness, Mr. Julian K. Roosevelt, at the Civil Air Terminal, and said later that Mr. Roosevelt, a keen yachtsman, knew Captain MacKay well, and had sailed with him on the ‘Bounty’.

Survivor Mrs. Penny Gudgeon said that she was not yet sure when she would be leaving Bermuda, and it is understood that the remaining survivors have not yet made definite plans to leave the island. During their stay here they had been living, free of charge, at the Bermuda Sailors' Home.

The main result of the inquiry, which was convened by a Commission set up on December 6, was the cancellation of Capt. Mackay's master’s certificate. But while the court decided that Capt. MacKay was to blame for the Ramona foundering on the reef off North Rock, they did not feel that his misconduct and incompetence were sufficient to render him liable to criminal proceedings, and no order for costs against him or the owners, Vagabond Cruises, Ltd., of the Bahamas, was made.

Vagabond Cruises were cleared of blame in hiring Captain Mackay to take the Ramona from Lunenburg in Nova Scotia, to the West Indies. Also cleared of any criticism were the people and organizations which took part in the rescue operation on the morning after the Ramona had struck the reef, and four of the survivors who gave evidence during the course of the enquiry were praised for their “courage and conduct.”

Mr. Roosevelt, who has competed in five Olympics for the United States, and sailed on the Newport-Bermuda yacht race on several occasions, said that he did not know Capt. MacKay before joining the ‘Bounty’.

Asked Mr. Nicholas Dill, Capt. MacKay’s attorney: "What impression did you get on first meeting Capt. MacKay?”

Mr. Roosevelt replied: “Capt. MacKay is not a very impressive looking chap, and as chief officer I was prepared to be a little wary of sailing under him. I thought that I would have to take command if anything went wrong. After I had been on board with him for half-a-day I forgot all my worries on that score, and I formed the opinion during that voyage that he was at least the finest seaman and navigator I have ever been at sea with.” He added that he had not seen the captain take a drink during the voyage of the ‘Bounty’.

Mr. E.W.P. Vesey, M.C.P., for the owners of the Ramona, said in his closing statement that there was no evidence that the vessel or her equipment were defective in any way when she put to sea from Lunenburg.

Mr. Francis Daly, for the Government, submitted that, in view of the complete lack of information about the wreck, no criticism could be made about the search for survivors. The boats put to sea quickly to rescue survivors quickly, he said, and it was thought at the time that there would be no search. Once the boats were at sea it would have been difficult to allocate search areas to them.

He also said that the Bermuda Government took part in such operations in a voluntary capacity. “This court may wish to recommend that in future the Government take less of a voluntary part, and give a lead and assistance to the people who perform the search and rescue operations.”

Mr. Daly replied: “The Government made £1,000 available this year for search and rescue.”

Mr. Palmer: “I was thinking not only of financial aid, but of the guidance and expertise of the Marine Board. The provision of grid maps for rescue boats might be worth discussion.”

A few moments earlier he had told the court: “If this can, now that five people have died, do anything to recommend, or ensure, that future mariners do not die that will be a fitting memorial to the people who lost their lives.”

The last attorney to make his closing address was Mr. Dill for his client Captain MacKay. He said that some evidence of the survivors and the captain conflicted. But there was also conflicting evidence between the survivors. The captain was exhausted because of the storm, he said, but still navigated accurately to Bermuda. He asked the court to say that conditions beyond Captain MacKay’s control drove the Ramona on to the reef.

Mr. Dill continued: “The main question is this. If the crew believed Capt. MacKay was affected by drink, and unable to perform his duties correctly, and was placing the ship in danger, why did they not remove him from duty? They had on board the mate (Joel Dresser) who was a former captain of the Ramona.”

Speaking of the events after the Ramona had struck, he said: “Had the crew stayed with the ship, as the captain commanded, there would probably have been no loss of life.”

In a 2-page covering letter to the Report dated 18th December, 1967, the President, Mr. Justice Barcilon wrote:

Your Excellency,

“We have the honour to submit the Report of the Marine Court of Inquiry appointed by your Deputy to inquire into the stranding of the vessel “Ramona C” on the reefs to the north of Bermuda.

The court was convened by a Commission issued on the 6th of December, 1967 to inquire into –

(1) the stranding of the vessel “Ramona C”;

(2) the deaths of five members of her crew;

(3) allegations of incompetency and misconduct of the captain of the vessel.

We find that the stranding of the vessel, “Ramona C”, was due to the incompetence and misconduct of her master, Captain William Ross Mackay, as above described.

With regard to the death of the five members of the crew, we are satisfied that Louis Martin Francis Desparest and Joseph Modeste committed suicide by drowning, while the balance of their minds was disturbed through physical and mental exhaustion.

We find that Dr. Kenneth Ross MacIntyre's death was due to accidental drowning.

The evidence regarding the death of Hendrickson Rene (sic) and Winston Thomas Simon was inconclusive, other than that it was due to drowning. We are unable to say with any degree of certainty whether they deliberately left the dory with the intention of accelerating their deaths or whether they passed out through sheer exhaustion and fell overboard. In respect of these two men, therefore, we return an open verdict.

We have considered whether the owners of the vessel were in any way neglectful in their selection of Captain Mackay as Master, and we have come to the conclusion that on the information available to them, they were not at fault in appointing him. It can only be a matter for conjecture whether the owners would have engaged Captain Mackay if they had known of his previous convictions for offences connected with drink.

The Court is empowered under section 40 of the Bermuda Merchant Shipping Act 1930, to order the payment of the costs of this Inquiry by the Master or owners of the vessel, but in all the circumstances of this case, the Court will make no order under that section.

In conclusion, we would like to convey our sincere condolences to the families of the five men who died in this tragic disaster.

In accordance with section 33 of our 1930 Act, a report of these proceedings will be submitted to His Excellency, the Governor. That report will amplify in detail our findings in this matter.”

[The Report itself, which formulates in detail the pertinent facts relative to the tragedy together with a keen evaluation of the witness’ evidence presented before the Court, can be viewed in its entirety at the Bermuda Archives, Government Administration Building, 30 Parliament Street, Hamilton HM 12.]

It will be remembered that the Coroner, the Wor. Walter Maddocks, had been quick to announce that he would take no action over the proposed inquest on the five victims of the disaster until he received orders from the Governor-in-Council – who were to meet two days hence on Wednesday, December 20.

Mr. Maddocks said: “When the Marine Court of Inquiry was set up, I was inhibited from continuing with the inquest, and that position has not changed. I expect I shall hear from the Governor-in-Council in the near future.” [On this point I could find no further communications setting forth a conclusion to this matter].

Two of the survivors, Mrs. Penny Gudgeon and Mr. Rosemond Harold had left the Bermuda Sailors’ Home where they had been staying since shortly after the rescue and it was thought that they had already left the colony. The remaining two, the mate, Mr. Joel Dressel and engineer Mr. Bernard Beaupre, were thought to still be in Bermuda.

In the calm days that followed the storm the yacht had been surveyed by a team of divers and the damage was not considered too great. The weather since then had not permitted further checks of the condition of the vessel, said Mr. Parker. He thought, however, that the steel-hulled Ramona may not have suffered very much more damage.

1968

The chairman of Air-Sea Rescue Mr. James A. Pearman said: “We will go ahead and look into this chart business and in the next two or three weeks we should be holding a meeting.

“We will eventually be making a report about it to the Ports Authority since they were the people responsible for our formation.”

"It appears that there has for some 18 months been in existence in Bermuda a loosely-formed committee, composed of volunteers, having as its object to assist in search operations when called upon to do so and to make recommendations to the Marine and Ports Authority regarding search and rescue operations. No such recommendations have as yet been made and it is to be hoped that the tragic stranding of the “Ramona C” with its consequential loss of life will spur the committee to submit such recommendations as they think fit, as soon as possible, in order that steps may be taken to set up an official organization for the conduct of these operations.

"In these circumstances, considerable allowance must be made for faulty recollection or observation and for honest mistake on the part of the five survivors. In respect of Captain MacKay, we made additional allowance for the fact that he was virtually standing trial on very severe charges and that he appeared to be temperamentally very nervous. Having made all reasonable allowances, we formed a very poor impression of Captain MacKay as a witness as compared to the other four survivors. There was direct conflict between the captain and the other witnesses regarding the quantity of alcoholic liquor he had consumed during the voyage and the conflict could not be accounted for by some honest mistake. One side or the other was deliberately lying, and we had no hesitation in accepting the evidence of the crew as against that of Captain MacKay.

“However accurate or otherwise the navigation of the vessel may have been until about 6 p.m. on the Saturday evening, it is certain that from then onwards the captain was guilty of culpable incompetence, no doubt induced by his excessive drinking. At 15.34 that afternoon, he had been able to fix his position to his satisfaction as being about thirty-five miles from Bermuda, and it was then clear to him that he would not be able to enter Bermuda waters in daylight. In our view, it was imprudent of Captain MacKay, under the prevailing conditions, to attempt to make a landfall that day, bearing in mind his knowledge of local hazards. As a competent navigator (as he is reputed to be) he should have realized that his observed positions, established by sextant under extremely difficult conditions, could well have been ten miles in error the wrong way.

“When the “Ramona C” foundered on the reefs, attempts were made by various persons on board to send up distress flares, with little significant success. Some failed to ignite, one backfired . . . only one flare went any height. Unfortunately, visibility conditions were poor that night – not more than five miles – and that one successful flare was not seen by anyone ashore. Consequently, it was not till about 7:45 next morning that anyone ashore knew of the stranding of the vessel.

“She had been sighted at a distance by Mr. “Speedy” Dickinson who was going out fishing that day. With commendable speed and initiative, he returned home and telephoned the police and from then on all possible local facilities were recruited to assist in what was then believed to be a rescue operation. It should be remembered that there was no information as the when the vessel had struck and for all anybody knew the survivors could well have remained on board to await rescue. In consequence of this absence of information, all available assistance was sent to the vessel in distress and no attempt was made to search the area between the “Ramona C” and Bailey’s Bay for survivors ….””

The text continued, in part:

“At a Marine Court of Inquiry held in Bermuda the yacht’s captain, Master Mariner William Ross Mackay, when asked by Mr. Anthony Palmer, Crown Counsel for the Court, to explain in one sentence why the tragedy had happened, said: “It was due to the ship being under-powered, and being unable to navigate her out of trouble.”

“Capt. Mackay said that about midnight of the 29th a gale blew up with winds reaching hurricane force, and the RAMONA sustained extensive external damage and some internal. Sails were lost and radar equipment damaged. In addition, most of the crew were disabled by seasickness. Capt. Mackay decided to put into St. George’s, Bermuda, for shelter and repairs. Meanwhile, on the 30th the radar equipment became useless and the radio was dead. Just before RAMONA struck the reefs, Capt. Mackay sighted breakers, but the yacht’s engine lacked the power to extricate the vessel from the danger area. At this writing the Court of Inquiry was still in progress. Divers who inspected the wreck when the seas had abated believed that the yacht was salvageable.”

Source: Bermudian Magazine, Vol. XXXVIII No.11.

Mr. Gascoigne noted that while no official report has been made to his board by the Air-Sea Rescue who were set up when the U.S. Coast Guard left Bermuda, the two groups have had valuable discussions together.

Mr. James Pearman, chairman of the Air-Sea Rescue Group revealed that his Group would be holding a meeting shortly at which the subject of a grid map of the Colony would be discussed. Such a map had been urged by some of the witnesses at the Ramona inquiry. It will help boats and aircraft engaged in a search, to know exactly where they are in relation to each other.

On the subject of the Air-Sea Rescue becoming an official group, Mr. Gascoigne commented: “The Air-Sea Rescue is doing good work, and costing Government nothing. If it’s to become official, Government will have to decide whether the cost is worth it.”

“We came to the conclusion," the report stated, “that we were not empowered to make an order against the owners, “Vagabond Cruises”, as they are not in these Islands, and we took the view that an order made against Captain Mackay would probably be of little value.

“In an event, bearing in mind the substantial financial loss suffered by the owners and the probable termination of the career at sea of the Master, we did not deem it either just or practicable that an order for costs should be made.”

The costs of the Inquiry were broken down as follows: Detention allowance paid to the survivors – £52; Witness money – £48.12.0.; fees payable to members of the Court and the Nautical Assessor – £117.12.0.; fees payable to the Clerk to the Court – £100; hiring of Typewriter – £6.

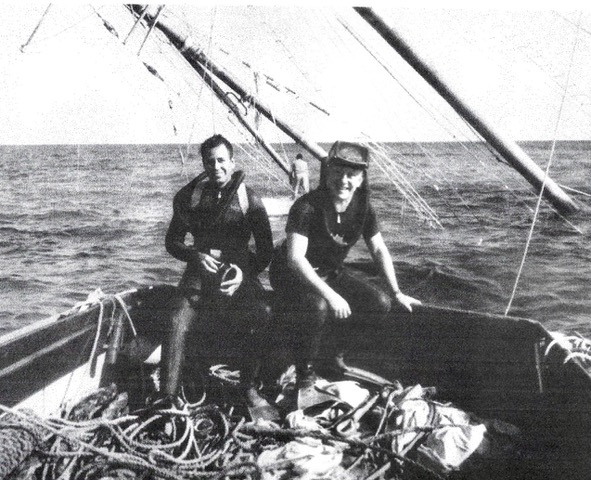

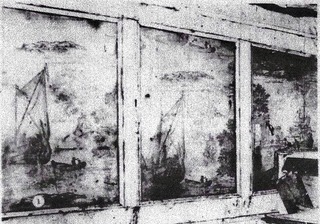

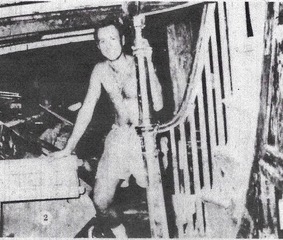

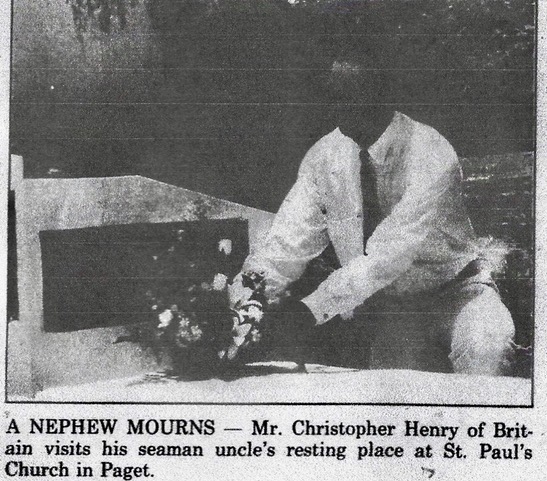

On Wednesday, January 24, 1968 the RG published the two photographs below, each with a legend. There was no additional comment reported.

DEATH YACHT

DEATH YACHT

Dear Sir:

I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to all the people of Bermuda who assisted us both verbally and materially after the tragic sinking of the yacht Ramona on Dec. 2 last. I would like to give special mention to Mr. Musson Wainwright and all those who took part in the rescue operations; Mr. & Mrs. Caleb Wells and the staff of the Bermuda Sailors’ Home for their kind understanding and benevolence; the Bermuda Police and all those too numerous to mention who made our stay on the island as enjoyable as possible under the circumstances.

An editorial in the RG on the same date opined as follows:

Although it is doubtful that the Coast Guard could have improved on the work done in connection with the Ramona sinking, at the same time it was lucky for the people on the yacht that the waters inside the reefs were calm, the sky clear, and the wind, on that Sunday, from the north so that the survivors were being pushed toward the shore instead of out to sea.

The committee on air-sea rescue are known to be actively working on their report, but what their findings will be is not known. It may be that they will find a need at least to call for some special training for the signalmen at Fort George, to whose multifarious duties have been added the responsibility for coordinating sea search.

Bermuda would be wrong to rely on Kindley’s Aerospace Search and Recovery Squadron. As the name indicates, their job is far more than attempting to look after downed planes, boats and ships in trouble in this area, for they are also responsible for taking an important role in space shots.

This not only means that on occasion they will be strained to the limit; it also means that sometimes most of their aircraft will be called on duty elsewhere. The squadron have done their best to help with local problems, but their job is a far bigger one.

So Bermuda must feel its way to its own organization. With Fort George and the Police boat and the volunteers we have the nucleus; with the much-discussed grid map and training (perhaps this might be little more than an exchange of ideas), we would be on our way towards a considerably stronger arrangement than we have at present.

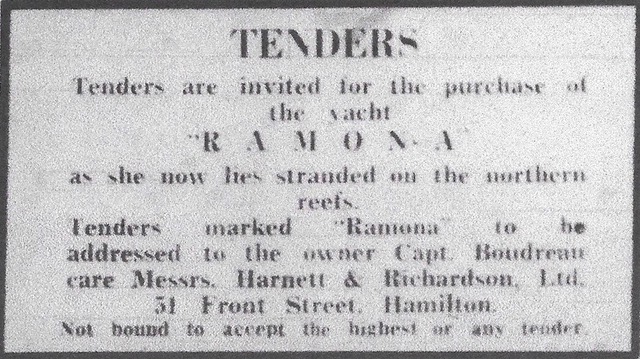

“It is understood that the yacht, ………., has been bought by three local men who submitted the highest tender of £2,500. A spokesman for Harnett and Richardson, who have been handling the arrangements for the sale of the 120-foot vessel, had confirmed that the deal had gone through. The owner Capt. Guy Walter Boudreau, of Nova Scotia, has been informed of the price offered by the local buyers.”

Revelations the following day named the new owners and told of their ‘simple plans’ to first recover the yacht.

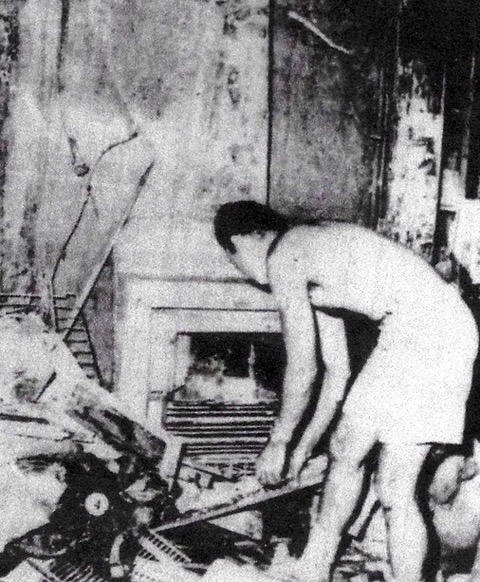

Elaborating, he explained that they intended to heave the Ramona into an upright position with the use of heavy anchors and chains. They hope that at low tide her deck will then be out of water. If the deck is not quite clear of the surface they intend to erect "coffer dam” constructions around the hatches to raise the effective height of the deck. After sealing any cracks in the hull or broken portholes, etc. the yacht will then be pumped out. Mr. Chiappa said the group had no immediate plans on what to do with the yacht once she is up, the main concern for the moment being to raise her. He said that they had dived on the wreck to examine her and she seemed to be in very good shape. Asked if he knew what was on board he said they had heard rumours of a cargo of linen and silver destined for a hotel in the Bahamas.

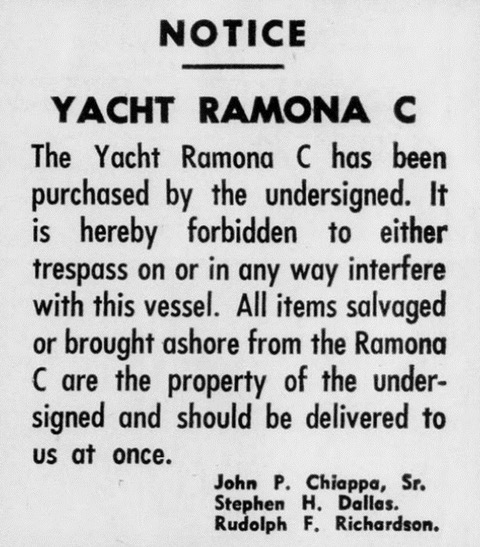

A Notice in the same edition of the RG warned the public to keep away from the sunken yacht and further advised them that any items removed from the yacht were the property of the new owners.

Mr. Stephen Dallas, one of the three new owners said,

“There’s a lot of work to be done before we can bring her up. I’ve been down and inside her, and although she looks a bit of a shambles at present you can tell she’s a lovely yacht.”

Mr. Dallas said that he will be doing most of the diving work involved, and will carry out a thorough inspection before the hull is pumped out.

“I have no idea at this stage just how long it’s going to take,” he commented. “These things often take longer than estimated anyway. I think we’ll get her up, though.”

Mr. David Gamble shackles a 45-gallon oil drum to the gunwale. Dozens of such

Mr. David Gamble shackles a 45-gallon oil drum to the gunwale. Dozens of such "We have already figured out a route through the reefs and we are making up marker floats now,” said Mr. Dallas. “She will have to come right out as soon as we get her up,” he said, adding with a chuckle that it would probably be just their luck that this would happen at sundown.

Also, the longer she remains on the reefs, the more she will deteriorate. Mr. Dallas said it was still impossible to determine whether there was much damage to the lower side of the yacht, but he thought that as long as she was under water she was somewhat protected from further damage. This is why she must be brought to port as soon as she is floated. The current weather, however, is of some concern. In the last four weeks since they acquired the yacht the salvagers have been able to work on her only two days — last Friday and the Saturday the week before that. Last Thursday they started out on what began as a good morning but had to turn back even before they reached the Ramona when the weather worked up. They hope to go out today if conditions will allow it.

[The “Ramona Resolve” was passed in the House of Assembly on Tuesday, March 6, 1968]