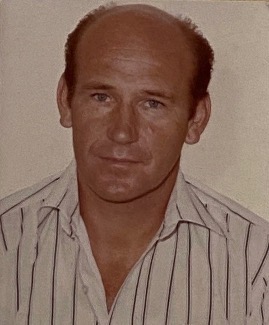

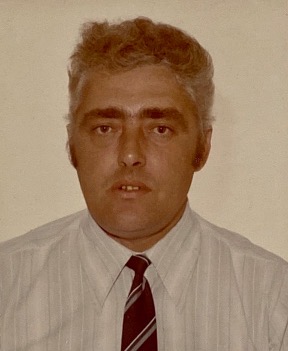

Standing at 6ft 4ins and weighing around 220lbs, Kenneth James Maxwell ‘Eggs’ Smith was a criminal who’d had trouble with the law throughout his adult life beginning in June 1966. Indeed, he was free on police bail some ten years later in August 1976 when he committed serious offences of burglary, rape and theft. This is the story of just one case involving the criminal career of one of Bermuda’s most notorious offenders.

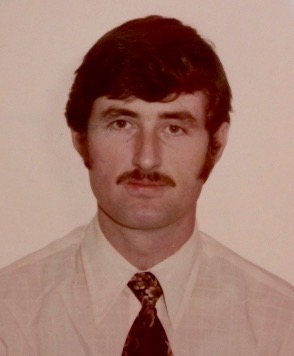

Night CID officers attended the scene and a good description of the offender was noted. SOCO officers including DC Willey began processing the scene whilst the victim was being medically examined and interviewed. In those days the science of DNA as an investigative tool had not yet been developed.

[As a matter of interest, in 1976 the Bermuda Police operated under the provisions of the Larceny Act 1916 wherein the definition of ‘burglary’ is stated as: –

Every person who in the night –

(1) Breaks and enters the dwelling-house of another with intent to commit any felony therein; or

(2) Breaks out of the dwelling-house of another, having –

(a) entered the said dwelling-house with intent to commit any felony therein, or

(b) committed any felony in the said dwelling-house;

Shall be guilty of felony called burglary and on conviction thereof be liable to penal servitude for life.

(The expression “night” was defined as the interval between nine o’clock in the evening and six o’clock in the morning of the next succeeding day:)

The Larceny Act 1916 was repealed in Bermuda in 2001 when amendments were made to the Bermuda Criminal Code Act 1907 relating to the definition of burglary in particular which effectively excluded any reference to the expression “night”.]

The search for Smith continued throughout that Sunday and concentrated around the central parishes including Bandroom Lane, Pembroke where he was last known to ‘hang out’ prior to his last imprisonment. The TBA (to be arrested) searches continued on a 24 hours basis by all police patrols during the following days and were concentrated mainly in Warwick parish where consistent sightings of him were being reported.

Later that day I was present at a conversation between DI Laurie Jackson and Smith and at 3.10pm in company with DC’s Steven Shaw and Maurice Pett I conducted a cautioned Q&A interview with Smith. Notes were contemporaneously recorded by DC Shaw at the conclusion of which Smith refused to sign the notes and was further detained in police custody. He denied knowledge of all matters put to him during the interview.

I was present shortly afterwards with DI Jackson and fingerprint officer DC Mervyn Willey when Smith voluntarily gave his permission for the taking of impressions of his footprints by DC Willey. Thereafter, Smith refused to sign the impression ‘print card

At 11.0am the following morning, Friday, August 27, 1976 on the railway trail near the Southampton parish post office, I conferred privately with Det Sgt. David Barber, officer in charge of the Western CID who was conducting investigations of housebreakings in that parish. I was again in company with DC Shaw and with DC Pett who was seated in the CID vehicle nearby beside a handcuffed ‘Eggs’ Smith.

My purpose in conducting the interview with Smith at that location was to give him an early opportunity to explain the circumstances surrounding any LAWFUL presence he may have had in the recent past at that location. A DENIAL by Smith of ever having been lawfully inside ‘Invicta’ would represent the lie which would serve to corroborate the forensic findings of the fingerprint officer.

He replied, “No.”

I asked him if he had ever worked on this house or in the gardens in the past.

He replied, “I told you, I’ve never been here before. Not me.”

I asked him if he was sure he had never been either inside the house or on the grounds before.

He replied, “I’m sure. Don’t know this place”

I told Smith I had reliable information that he had broken and entered this house known as ‘Invicta’ last Friday morning the 20th August when he had assaulted and raped the

female occupant and had stolen cash from her purse. I told him that after gaining access I believed he had walked barefooted down the hallway inside the house towards her bedroom. I asked him what he had to say to this allegation.

He replied, “Not me. Prove it.”

I then continued this same line of questioning after travelling with Smith in the CID car to other dwelling house locations in the parishes of Smith’s and Southampton including those named ‘Ranaway’; ‘High Roods’; and ‘Feathers’. Thereafter, we proceeded to a house named ‘Sea Swept’ in Shaw Park, Spanish Point, Pembroke parish.

After refreshments we resumed at 3.30pm and in the same manner DC Shaw recorded my interviews under caution with Smith at premises known as ‘Magnolia Hall’; ‘Landmark’; ‘Sea Quest’ Lolly’s Well; and at Rocky Heights No. 2.

Smith maintained his denials that he had ever – lawfully, or unlawfully – entered any of the said premises we had visited.

Smith refused to sign any of the recorded interviews after they were each read over to him in turn and, at 5.35 pm, we returned to the office when Smith was further detained.

From that point on I was purposely not involved in any of the subsequent identification proceedings. [Read these detailed proceedings in the following trial testimony of DCI Donald]

During the morning of Sunday, August 29, I separately recorded witness statements from two female complainants’ directly after their independent participation had ended in their two identifications of Smith. [This second female complainant involved a totally separate matter to that involving the incident at ‘Invicta’].

“I’m sorry.”

“I told you, its drugs.”

“Okay, drugs are to blame.”

He refused to sign the charge sheet.

Following on from that determination, later that afternoon in company with DC Pett I read over to Smith his Supreme Court convictions to date as a preparatory step towards the application of an ‘adjudged term’ of imprisonment otherwise known as preventive detention.

I left a copy of the record of his previous convictions with Smith and with the Registrar of the Supreme Court. When asked if he had anything to say Smith replied:

“It’s about right. That’s cool.”

He refused to sign a receipt of his copy saying, “I don’t have to.”

“A school teacher pointed to Smith in the dock as the man who broke into her house last August 20, raped her and threatened to kill her if she screamed, while she tried to reassure her young son in the next room that nothing was wrong.

The second charge involved stealing $55 from her purse.

The Puisne Judge, the Hon. Mr. Justice Seaton, ruled that the woman’s name and address should not be published.

Crown Counsel Mr. Robin McMillan asked that the court be cleared of all but court staff and parties concerned in the case while the complainant gave evidence, because of the possible effect on the teaching and disciplining of children in view of her occupation.

Defence Counsel Mr. Wendell Hollis said the defence did not wish to cause any undue embarrassment, but the woman had brought complaints against Smith and such important information must be weighed in the balance.

Mr. McMillan cited a provision in the Bermuda Constitution that a court might exclude the general public “in circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice, or in interlocutory proceedings, or in the interests of public morality, the welfare of persons under the age of 18 years or the protection of the private lives of persons concerned in the proceedings.”

The Judge said the court had the power to clear the courtroom, and he himself had done so in a similar case involving a 15-year-old pregnant student.

“But,” he added, “I have never before, in any case involving adults, asked that members of the public should leave the court. Now, of course, the court has been given the power to withhold details of personal affairs, of name, address and that sort of thing, from appearing in the press. The reason for that is that persons who are victims of such attempts would perhaps be reluctant to make complaints if their names were to be on everyone’s lips.

“But when we are asked to clear the court when a witness is giving evidence, it must be remembered that the principle of holding an open court is for the protection of the complainant and also of the public, so everyone should see that not only is justice done, but it is seen to be done.

“This has a salutary effect on the witness, who might be tempted to give false evidence if there were no members of the public present. And it has an effect on the accused, who perhaps feels that justice will more surely be done if the public is there to see him. And it has an effect on the judge, who knows that his conduct is being judged.

“I cannot see that any great injustice is being done to the witness, who is not appearing before a great crowd of people, but before the limited number who may be interested in coming to court.

“So far as her students go, her name will not appear, and they are of such an age that no effect on teaching is involved. On balance, I do not feel that it would be right or necessary in this case to order people to leave the court. If I were to do it in this case, then I should do it in every case.”

Crown counsel said the basis of his application was the sensitive nature of the woman’s employment.

The Judge replied, “If there was a student in court, I would consider it more serious, but I don’t think many students come to court. I don’t think it is necessary.”

Outlining the prosecution case, Mr. McMillan had said the complainant identified the defendant on August 29 [1976] at Hamilton Police Station.

A doctor at the King Edward VII Memorial Hospital found a laceration on her lower lip, and evidence of recent sexual intercourse.

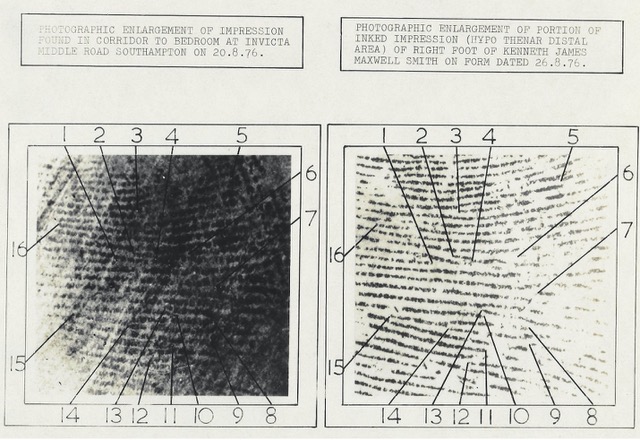

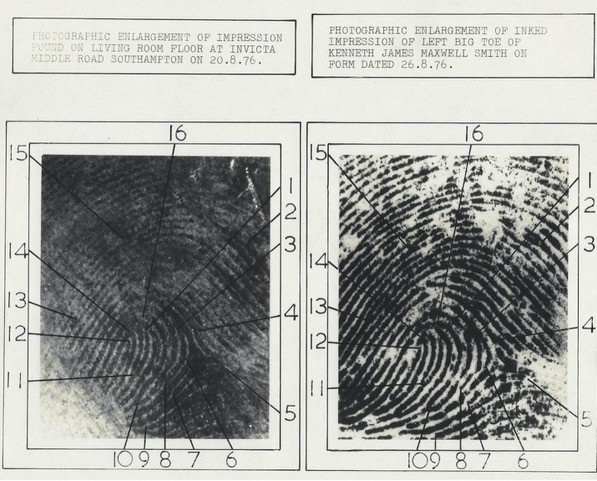

DC Willey went to her home shortly afterward and found impressions of a footprint which proved identical with those voluntarily given by the defendant.

The first prosecution witness was the complainant who said she was a divorced British subject with two children, of whom one – a 10-year-old boy – lived with her.

On August 19, she picked him up from his sailing lesson off White’s Island and took him to Castle Harbour for a swim. They got home after 8 p.m., after stopping to pick up food. Her son went to bed at about 9 p.m., and she retired about an hour later.

The screen door and front door were locked, and there was also a security lock with a chain. The kitchen door was normally kept locked with two slide locks. After securing all locks, she went to sleep. She got up and opened a bedroom window screen to let the cat out, then went back to bed and straight to sleep. She was not wearing a nightgown, but there was a blanket across the lower part of the bed.

“I woke up because the blanket was being moved …. There was a man kneeling at the side of my bed on the floor. I was immediately very still, and he looked up at me, and then I screamed, very loudly.”

“He leapt onto the bed on top of me and bit my face and lower lip and put his hands on the side of my face. He said, ‘Don’t scream or I’ll kill you,’ in a fairly loud voice.”

“After I had screamed, I could hear my son screaming in the bedroom next door, calling

‘Mum, Mum, what’s the matter, what is it?’

I shouted, ‘It’s alright.’

I told the man ‘That’s my son, let me go to him.’

“He said no, and insisted on having intercourse with me. He had no clothing on; he had something on his head which I couldn’t see properly …. He raped me.”

“I was talking with my son the whole time. I did tap him on his back - I wanted to calm him down. My son was screaming and crying, I was talking the whole time, telling him to stay where he was, that it was all right, that he wasn’t to come out of his bedroom.”

“The man got up and sat on the other side of the bed. He said he would be dead tomorrow, that he would get sent up for this. I said he should leave, and quietly, so as not to disturb my son. I told him ‘I won’t call anybody – just go.’

“He didn’t go, - he was there for about 10 minutes. He did talk about my calling people, that I would call police. I kept saying all I was concerned about was my son and sorting out myself.”

“He went to the door of the bedroom, then came back and picked up what seemed to be his shirt. When he left the house, I waited because I wanted to hear him out of the house before I got up. He went out by the front door; it was open, it had been locked.”

“My son was hysterical. I told him somebody had lost their way. I told him ‘We’ll put all the lights on,’ and we did. Then I called the police.

“When I woke up, it was fairly dark; when he left, it was the twilight before dawn. I also picked up my watch and looked at the time; it was about six o’clock. At first I could not tell what colour he was. When he was sitting on the side of the bed, I looked at him very hard, and knew he was coloured.”

“There was sufficient light to see furniture and his features. The front door was ajar, and the window was wide-open that leads to the porch. The blanket my son had on his bed was draped over the lamp that sits on my desk.”

“My purse was lying open on top of the books on my desk. It had contained a $20 bill, a $10 and about two $5’s. The blanket was on my son’s bed when he went to bed. The man came through the window onto the porch; the screen was out, against the wall. He went out by the front door.”

“I had never seen him; I would be able to recognize him again. He was a very tall man, well built, muscular, with a big mouth and a big nose. That is the man, sitting in the box.”

Asked by Crown Counsel to point to him, she did so and said “There”.

She said she went to Hamilton Police Station on August 29 at the request of police and spoke with (Inspector) Clive Donald and others.

“I was taken to a room …… On the opposite side of the room was a bench. On the bench was a man in a blue outfit. I looked at him – it seemed to be a long time. I saw the man that was in my room - the man that is sitting in the box. I know that man raped me.”

Cross-examined by Mr. Wendell Hollis, the teacher said she had been in Bermuda just over ten years. She had [redacted], and a son living with her in Bermuda. She said she had read through her statements to the Police before coming into court that morning.

On August 19 she had picked up her son and gone to the Castle Harbour Hotel where she watched him swimming. On the way home they picked up some hamburgers. She put her son to bed first, and she followed at about 10pm. She locked all the doors before retiring. She slept with no clothes on – that had been her normal practice, but not any longer. She was half-covered by a blanket, and woke up to find a man in her room.

“I was appalled,” she told the court. She screamed, and was positive she had done so.

“He said: ‘Don’t scream, or I will kill you.’ I am absolutely sure he said that,” said the teacher in answer to questions.

Counsel pointed out: “But you told the Police officer ‘he said something like don’t scream or I will kill you?’”

Witness: “That’s right. The detail and order of words may be different.”

She said that at this stage she called to her son that she was alright.

“I told him that it was alright, to stay in bed, not to come out,” she said.

The man would have heard her say that. The man got onto her bed, and bit her lip. It could not have been a “misconstrued” kiss. He was lying on top of her. She was talking to her son all the time.

She was asking the man to let her go to her son. She told the man her son had had a good day, and not to spoil it for him. She tapped him on the back in an effort to calm the man down.

“You were not fighting?”

“Definitely not.”

“Did he say something like there will always be love, and didn’t you answer ‘yes, there will be?”

“Yes.”

He sat on the bed talking to her afterwards, and she was talking to him. She said there was sufficient light to see the shape of the man’s head. Witness said she could not be sure how much was in her purse, but she knew there was a $20 bill and some other bills. She agreed that the man in the dock was the man who had come into her house, and that she had never seen him before.

She said she felt a scar on the man, but did not know where it was. She had the impression he was a construction worker. He did not sound like a Bermudian, and had an English sort of accent, and a crude sort of speech.

She was taking birth control pills at the time for personal reasons. She had a boyfriend at the time with whom she had sexual relations. She refused to say for how long, and also refused to answer a question about whether she had had sex with other men in Bermuda.

The Judge said it was not his policy to compel witnesses to answer questions. Whether they did or not was up to them.

Said counsel: “Didn’t you consent to have sexual intercourse with that man?”

Witness: “I did not consent to have sexual intercourse with that man.”

Re-examined by prosecuting counsel, witness said she was not fighting the man off for specific reasons. Three years ago she began health, family life and sex education in her teaching and had attended two university courses on the subject. The nature of the courses had been human sexuality.

She replied to a question that she did not teach on the question of rape in the class-room specifically, although the subject had been brought up by the children, and she had given advice,

“I have said the victim of rape is liable to tremendous physical damage if she fights off an attacker, and this has been proven,” she said.

Counsel: “Did it have any relevance to your attitude on this occasion?”

Witness: “It is the whole background to my not giving any physical opposition to the rape. I tried to talk him down. I thought it important to de-emotionalize the situation and try to get him out.”

“Would you say you were successful?”

“Yes, I would.”

The Judge thanked the witness for giving her evidence, saying for her it may have been an embarrassing experience.

Pathologist Dr. Keith Cunningham, who examined the previous witness the morning of the alleged incident, said apart from the wound on her lower lip, there were no other recent external injuries. Following an internal examination, he concluded that “there was evidence of recent sexual intercourse – recent in terms of hours.”

The lip injury was consistent with a bite.

On cross-examination, he said the object was consistent with any object sharp enough to break the skin. It could have been the result of a misdirected kiss, from tooth to lip.

DC Mervyn Willey, who said he had been a fingerprint officer for 10 years, went to a house on the morning of August 19, [date should read August 20,] and examined a window for fingerprints. None were found.

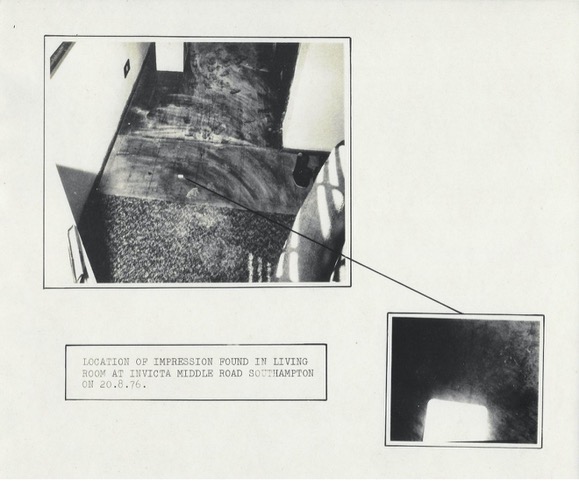

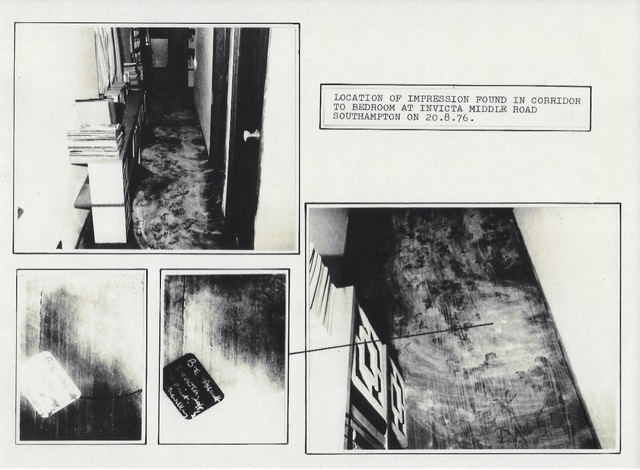

Following information received, he examined the living room floor and found a footprint, and two impressions in the corridor leading to the woman’s bedroom.

DC Philip Bermingham was called to the stand to give evidence of photographing the impressions, and what had happened to the film.

DC Willey was recalled after some legal argument in the absence of the jury, consisting of eight women and four men.

Mr. Hollis said it might be unsafe to rely on the film, on the ground that it could not be traced to a particular photographer.

Crown Counsel said this would not appear to be vital.

“The Crown seeks to introduce film in the custody of DC Willey which has been developed. What matters is that he did his job, we have got the stuff here, and my friend is trying not to let the jury get a look at it.”

The Judge observed,

“It may be that there is no conflict. I have to ask myself, if there is, is it for the Judge to decide or the jury? So, I propose to adjourn until 9:30 tomorrow morning.”

Mr. Robin McMillan prosecuted for the Crown and Mr. Wendell Hollis appeared for Smith. As reported by the RG the following day:

“Mr. Justice Seaton ruled an album of photographs of footprint impressions was admissible as evidence. On Monday, Mr. Hollis had said it might be unsafe to rely on the film, on the ground that it could not be traced to a particular photographer. Mr. Justice Seaton said the matter had given him quite some anxiety, but on balance he had come to the conclusion that it should be admitted as evidence.

DC Mervyn Willey, questioned by Mr. McMillan, said that on August 26, as a result of a telephone call, he went to the C.I.D. in Hamilton and saw the accused.

Det. Insp. Lawrence Jackson asked Smith if they could take his footprints and he agreed, requesting that they take care not to harm the sores on his feet.

DC Willey said Smith’s feet were in a very rough condition because he had been barefoot. DC Willey said he took several impressions of Smith’s feet and that the three exhibits being produced were of Smith’s big toe on the left foot, of Smith’s right foot and of Smith’s left foot.

DC Willey said that Smith refused to sign a form stating the impressions were of his feet and the officers present had endorsed the form to that effect. DC Willey also produced a diagram of Smith’s left foot showing the individual areas to which he would refer.

He explained that the principle of taking footprints was similar to fingerprinting in that on the soles of the feet extending to the toes were friction ridges, like those on the palms of the hands extending to the fingers. Friction ridges ran parallel but tended to deviate and form patterns on the toes and fingers. It was possible to positively identify footprints by looking at the position and sequence of the friction ridge characteristics.

Mr. Seaton said: “I am supposed to decide whether this man is expert in footprints. I want to know what he claims to know about footprints. Would you tell us if you have training or expertise in footprints?”

DC Willey replied: “I am trying to explain that the procedure for the two is the same.”

Mr. Justice Seaton asked how many footprints DC Willey had identified in the course of his experience. He replied that he had identified four footprints and hundreds of fingerprints.

In reply to further questions from Mr. McMillan, DC Willey said that having taken the foot impressions, he immediately returned to the fingerprint department and compared the impressions he had taken with footprints found at the complainant’s home. He said he compared the impression of the left big toe with the print found in the living room at the house. “I found the two to be identical,” he said.

Subsequently, he compared the impression found in the corridor of the house with the impression he had taken of Smith’s right foot and found those impressions to be identical.

DC Willey said he had enlarged by five times Smith’s toe impression and the footprint found in the living room. They showed 16 friction ridge characteristics in agreement by position and sequence.

“This indicates there is no doubt whatsoever that the two impressions are identical,” he said. He said he had done the same with the impressions found in the corridor and the impression he had taken of Smith’s right foot. This also showed the impressions to be identical.

Mr. McMillan asked DC Willey how many agreeing characteristics he would be satisfied with in a comparison of impressions. DC Willey said eight points were sufficient to establish positive identification.

“Are you in a position to say the footprints categorically belong to one person?” Mr. Mc Millan asked.

“There is no doubt whatsoever that the footprints belong to the accused,” DC Willey replied.

He said that it was easier to match up footprints than fingerprints because there were more friction characteristics on the foot than on the hand.

Cross-examined by Mr. Hollis, DC Willey was asked if any attempt was made to take footprints anywhere else in the complainant’s house. He said they tried in the bedroom with a negative result and similarly by the windows.

DC Willey said another print had been taken in the bathroom which did not belong to Smith and which had not been identified.

Mr. Hollis asked DC Willey if Insp. Jackson had told Smith he had a right to refuse to have his footprints taken. He replied that he believed so but he could not be sure.

On the cuts to Smith’s feet, DC Willey said they were mainly to the edge of the instep. Asked if any sign of discharge from the foot sores was found in the complainant’s house, DC Willey said that none was discovered to his knowledge.

“Mr. Hollis asked DC Willey if it was not possible for two people to have the same prints. He replied that no two people’s fingerprints or footprints were identical. No more than four friction characteristics agreed on two people’s prints and eight were needed for a positive identification.

Det. Sgt. George Rose was then called to give evidence. He said that on the morning of August 27, he was in an unmarked police car with DC Steven Shaw and DC Maurice Pett and Smith at a time when Smith was in custody.

The car was not moving and he conducted an interview with Smith while DC Shaw took notes. He said he asked Smith if he had ever seen the house nearby before. Smith said he had not and that he had not been in the vicinity before. Asked if he had been in the grounds of the house, Smith said no.

Sgt. Rose said he told Smith he had information that the house had been broken into and money stolen and that the intruder had had forcible sexual intercourse with an occupant of the house. He asked Smith if he knew what he was talking about and he said he did not.

“I said to Smith – I have reliable information that you broke and entered this house last Friday and committed theft and rape. What do you say to this?” said Sgt. Rose.

He said that Smith replied that he knew nothing about it.

Sgt. Rose said that later that day, outside Hamilton Police Station, Smith was asked to sign that DC Shaw’s record of the interview was correct and he replied that he never signed anything.

Cross-examining Sgt. Rose, Mr. Hollis asked him where Smith had spent the night of August 26. He replied that Smith had been in custody at Hamilton Police Station.

Mr. Hollis asked if Smith was exhausted and confused when he was taken into custody. Sgt. Rose said that when he saw Smith he appeared to be relaxed and his conversation was intelligent.

Mr. Hollis asked Sgt. Rose if it was correct that after the interview on August 27, Smith had said that he had been high on drugs, was not feeling himself and could not remember the details. Det. Sgt. Rose said that was correct.

Det. Insp. Lawrence Jackson was called as a witness by Mr. McMillan. Under cross-examination, Mr. Hollis asked him if he had told Smith that he had a right to refuse to give his footprints. He said he merely asked him if he wished to give them.

Mr. Hollis asked Insp. Jackson if he was aware that had Smith refused, the matter would have had to be taken to a magistrate. He said he realized that.

“Did you think it would be only fair to tell him he had a right to refuse?” asked Mr. Hollis.

“I asked him and he said yes,” replied Insp. Jackson.

Det. Chief Insp. Clive Donald, the next prosecution witness, said he saw Smith at Hamilton Police Station on August 28 when he asked him if he wished to go on an identification parade. Smith said he did not want to go on one.

Insp. Donald said he explained to Smith that if he did not wish to go on a formal parade, he could go on a street parade. If he would agree to neither of those alternatives, he could be seen by the witness in a room with about six other men or have a confrontation with the witness by himself in the presence of the police.

He said that he explained the advantages of taking one of the first three to Smith, but he did not want to take part. Smith said he did not want a lawyer.

Insp. Donald said he returned to see Smith the next day [Sunday, 29] and Smith said he still felt the same way about the parade.

A confrontation took place between the complainant and Smith in the charge room.

The complainant was asked if Smith was the man she had seen in regard to a report she had made to police on August 20. She appeared distressed and said: “Yes, yes.”

Mr. Hollis asked Insp. Donald whether any effort had been made in the week between the offence and the confrontation to get an identification from the complainant. He said none had because they could not arrest Smith.

Insp. Donald said she was never shown a photograph of anyone else because police had suspected Smith from the first day.

After lunch, Mr. Hollis called Smith to give evidence.

Questioned by Mr. Hollis, Smith said he was born in Bermuda and had lived here all his life. He agreed that he had heard himself nicknamed ‘Eggs’ Smith, but said it was a name given to him by the Police and not by himself or his friends. He had got the name because Police had confused him with a man called ‘Eggs’ Trott.

Mr. Hollis asked him if he knew anything about the incident on August 20. Smith said he did not.

“Had you ever met the woman before the confrontation at the police station?” Mr. Hollis asked.

Smith replied: “Never before in my whole life.”

Mr. Hollis: “Do you remember ever having sexual intercourse with her?”

Smith: “No, sir.”

Mr. Hollis: “Do you remember every going to her house before being taken there by Police?”

Smith: “No, sir.”

Mr. Hollis: “Do you remember anything about the period when this alleged offence took place?”

Smith: “I don’t remember anything. I was taking drugs and drink.”

Smith said the drink and drugs caused him to remember nothing of that time.

Answering further questions from Mr. Hollis, Smith said the first he remembered of that time was being in the police station. Asked if he had any detectable scars on his body, he said he had none and he denied ever wearing a turban.

“To your knowledge, did you rape this woman?” asked Mr. Hollis.

“No,” replied Smith.

Smith said that to his knowledge he had never taken any money from the woman or been to her house.

Cross-examining Smith, Mr. McMillan asked him if he was quite sure he had lost his memory of that time. Smith said he was sure.

“So, if I put it to you that you raped the woman, you can’t remember?” asked Mr. McMillan.

“I never raped any woman. I could never see myself doing such a thing,” Smith replied.

Mr. McMillan asked Smith what condition his feet were in at that time.

He said he had a gash on his foot but denied that he got it because he was running around the island barefoot.

Summing up for the prosecution, Mr. McMillan said this had been one of the shorter cases before a Supreme Court jury but this was a serious offence.

“Rape is one of the most evil crimes you can imagine,” he told the jury. Socially and historically, it is one of the worst crimes.”

He said that defence counsel had said that whoever had intercourse with the complainant had it with her consent.

Mr. McMillan asked the jury whether it was likely that a woman like the complainant would consent to intercourse with a stranger who jumped through the window.

He described the photographic evidence of footprints as deadly evidence against Smith.

In conclusion, he said it was for the jury to decide whether the accused was the victim of a woman telling lies or whether the accused was a depraved, dangerous and evil man.

Mr. Hollis, in his summing up, asked the jury to keep several things in mind. He said that the woman admitted in her evidence that the light was bad. She had said there was a scar on the man’s body, but Smith had denied it.

“She had said the man had an English accent but Smith was Bermudian.

On the footprint evidence, he reminded the jury that no prints had been found in the bedroom or by the windows but an unidentified print had been discovered in the bathroom.

Smith had said he could remember nothing of the time of the offence, Mr. Hollis said. It was up to the prosecution to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that the accused was guilty.”

When addressing the jury in answer to their question on intoxication, the Puisne Judge pointed out that a verdict of not guilty could be returned if the jury believed the accused was intoxicated by drugs or drink to such an extent that he did not know what he was doing, but only if the accused was intoxicated involuntarily.

He stressed that no evidence had been produced by the defence to prove the accused had been intoxicated involuntarily in some way.

The RG reported on the outcome on Thursday, December 9, 1976:-

“Kenneth James Maxwell “Eggs” Smith was found guilty yesterday by a Supreme Court jury of rape and burglary.

The seven-woman, five-man jury adjourned to consider [its] verdict just after 11 a.m. and [was] summoned back into court by the Judge, who addressed them further on intoxication of drugs and drink.

The jury returned to court at 3 p.m. to ask the Puisne Judge a question about intoxication and delivered their majority guilty verdicts on both counts 15 minutes later.

The Puisne Judge thanked the jury for their “application to duty”. He described the case as difficult and adjourned sentencing until today to give Crown Counsel time to consult with the Attorney General on further charges against Smith.”

[In relation to the imprisonment or preventive detention of an offender, the term to which the offender was sentenced by a court was known as an “adjudged term”. Such sentencing procedures were repealed with effect from 29 October, 2001]

“Det. Sgt. George Rose told Mr. Seaton yesterday that Smith was a 27-year-old Bermudian who had been unemployed for a considerable number of years. He said that Smith had spent several periods in St. Brendan’s Hospital and had been known to be unpredictable. He had a tendency to be influenced by other criminals but often worked alone, as in this case, said Det. Sgt. Rose.

He had lived on the proceeds of his crimes for several years, with no proper home beyond prison. His family life was non-existent and he had often used drugs as a means of combating life’s problems.

“He has been disowned by his father and is completely beyond the control of his mother whom he rarely sees,” said Det. Sgt. Rose. He said that Smith had been on police bail when these offences were committed.

Smith’s previous convictions during his adult life dated back to June of 1966, he said, when he was given a period of corrective training for trespassing dwelling houses and prowling.

In June 1967, he got more corrective training for trespassing [in] a dwelling house and violently resisting arrest.

In December of the following year, he was sent to prison for four months for shoplifting.

In January 1969, Smith was sentenced to six months in prison for burglary, and later that year he was ordered to go to St. Brendan’s for breaking, entering and stealing.

In August of 1970 he was given a conditional discharge and returned to the hospital for stealing by way of finding.

In February 1971, he received a three-and-a-half year prison sentence for housebreaking, unlawfully wounding a Police officer, possessing a dangerous weapon and violently resisting arrest.

In 1973 Smith was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for housebreaking and theft.

Mr. Wendell Hollis, defence counsel, speaking in mitigation for Smith, said his client could not help the court as to what happened on the day of the offence because he could not remember what had happened at that time.

“He has said the reason he can’t remember is because he was under the influence of drugs and drink to a very deep extent at this time,” Mr. Hollis said. The reason he took these drugs and drinks arose out of a feeling of depression on his part. He felt persecuted by the Police and because he could not find a job. This is regrettable and sad.”

Mr. Hollis said Smith’s whole life, from the age of 11, was very sad. He was first sentenced to corrective training when he was 11.

“This form of treatment at such an early stage in his life may have led him to this courtroom today,” Mr. Hollis said.

Smith could not read or write adequately and this lack of ability could affect one greatly in life. He said that the last time Smith was released from prison no rehabilitation was undertaken even though Mr. Seaton had suggested it should be at the time. There were no proper institutions in Bermuda to deal with persons like Smith, he said, although such institutions from which he could probably benefit greatly, did exist in other places.

He said he strongly urged that all steps be taken to rehabilitate and train Smith and that this should be on the conscience of the prison service and the social services.

“He should not be ignored and he should be looked upon with compassion – and not in a way which would lead him to believe there is no hope for him. Everyone should have hope in life. That more than anything else should not be taken away,” said Mr. Hollis.

He was distressed that an application had been made for preventative detention because he believed it was a harsh and outmoded concept. Mr. Hollis asked Mr. Justice Seaton to give Smith as much mercy as he could find.

Smith told the Puisne Judge that he had not been given any help with rehabilitation when he had been released from prison and that he found it hard to cope. He said he felt he was deprived as a child and corrupted at an early age. He claimed that Police treated him like an animal, chasing him about and trying to make a fool of him in front of his friends.

Sentencing Smith, Mr. Seaton said that defence counsel had brought to the attention of the court matters which for some time had caused distress to some people whether or not they were concerned with the administration of justice. He said people in Bermuda lived in a community which was small and rather tight-knit. If someone was so unfortunate as to get into trouble at an early stage, unless great care was taken, there was likely to be a feeling of depression and repeated periods of custody in one institution or another.

It was possible in other countries to remove someone to another town or state and give them the chance to start a new life. People in Bermuda, who had been in trouble previously, had great difficulty if they wished to go straight, said Mr. Seaton.

“What seems to be needed is some sort of system midway between prison and complete freedom where persons can work and live before returning to normal life and after serving their sentence,” he said.

He urged that everyone concerned with the well-being of the country would try to find a solution to the problem. He said he was of the view that he could not do otherwise than order that Smith be detained for a period of preventative detection for ten years.”

Dear Sir,

We represent the victim of rape and robbery which took place on 20th August, 1976 for which Kenneth James Maxwell “Eggs” Smith was tried, convicted and sentenced and have been instructed to write to you and the Royal Gazette complaining about the report of the trial which appeared in the Royal Gazette and in particular the report which appeared in their issue dated 7th December, 1976.

The reason our client has so instructed us is because she is genuinely concerned about protecting the rights of other persons who might be in similar circumstances and the community generally by helping offenders to be brought to justice.

Among the personal particulars about our client which the Royal Gazette printed were the following:

(a) “… she was a divorced British Subject with two children of whom one – a 10-year-old boy – lived with her”

(b) She is a teacher who “had been in Bermuda just over ten years. She had [redacted] a son living with her in Bermuda”.

(c) “Three years ago she began health, family life and sex education in her teaching and had attended two University courses on the subject”.

The provisions of the law governing such reports which were called to the attention of Mr. Justice Seaton by the prosecution at the trial were as follows:

(i) Bermuda Constitution Order, 1968 Sect. 6 (10) (a) which provides that the court proceedings need not be held in public in circumstances where “publicity would prejudice the interest of justice, or …. the welfare of persons under the age of eighteen years or the protection of the private lives of persons concerned in the proceedings”.

(ii) Criminal Code Sect. 543 (i) which provides that in any rape trial if “it appears to the court expedient in the interest of the protection of the private lives of the persons concerned with the proceedings, the court may, on the application of either the prosecutor or the accused person, direct that” the general public “be excluded from the court during the taking of the evidence of any particular witness”.

(iii) Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1943 Sect. 1 (d) which provides that in any rape trial it shall not be lawful for any person to publish “the name, address, or other personal particulars of the complainant or prosecutor in any case where the presiding Judge” so orders.

The Prosecution and our client applied to the Judge to clear the court under the provisions of (ii) above while our client gave evidence and the Judge refused the application.

In our respectful view the Judge was wrong in so doing.

The Prosecution and our client applied to the Judge to order the press not to publish the name, address and other personal particulars of our client under the provisions of (iii) above and although there may be some doubt as to what the Judge did order, it appears to us he invoked the relevant section and that the particulars published by the Royal Gazette contravened the Act.

We appreciate that some of the above mentioned legal provisions are of recent origin and that the Royal Gazette may have erred through unfamiliarity with them and for this reason we again respectfully attribute some blame to the presiding Judge for not explaining the position in Court.

Little can be done now to undo the injury personal and professional which has been inflicted upon our client, but she is interested in safeguarding the rights of persons who may find themselves victims of similar outrages.

Such persons obviously will be able to call on the police, who our client advises behaved in an exemplary manner in her case, but they will not be willing to go to court if doing so involves the ordeal to which our client was subjected.

The description came from Mr. Wendell Hollis who represents Smith, 27, in his appeal against both conviction and sentence for the rape on August 20 last year and for burglary of the same woman on the same night.

Smith appealed on the grounds that the verdict was unreasonable and could not be supported by the evidence, and that the sentence of ten years’ preventative detention was unduly harsh and excessive.

At the beginning of the hearing on Monday, Mr. Hollis said the case was broadly one in which the prosecution had to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that Smith raped the woman and committed the offence of burglary in her house. In his submission, it had not done so.

Smith’s evidence was that he had no recollection at all of the events of that evening. He was the only witness for the defence. His reason for having no recollection was that at the time he was under the influence of drink or drugs, and remembered nothing of the event until he was apprehended by the Police over a week later.

“The evidence was given to explain why Mr. Smith himself could not comment on the evening, which meant that the jury could only review the case through the prosecution’s evidence,” said Mr. Hollis.

The first witness was the complainant, who gave evidence of events during the day before the incident, and of retiring to bed that night. Her son was in an adjacent room. She awoke to find a man beside her bed. She had said the man told her: “Don’t scream, or I will kill you.”

Her son had awoken at this point, and she had said: “It’ alright.” Mr. Hollis said the complainant had gone on to describe the sexual act which had taken place, and her behaviour towards her assailant.

She had said: “I did nothing while the act was taking place. I did tap him on the back. I wanted to calm him down. I could not recollect saying anything to the man.”

She had told the court that her purse was open, and the wallet inside, contained a number of bills adding up to almost $60. That, said Mr. Hollis, was the only reference to the money which was alleged to have been taken.

She had described the man to the Police as being tall, muscular, a big man with a big mouth and nose.

At the Police Station she had been taken into a room where a man dressed in overalls was sitting on a bench. She said she recognized the man as her assailant. She said she had not been shown photographs by the Police. There was only one man in the room.

The man, she said, had a large scar on his body which she felt during the incident, but she did not remember on which part of his body. He had not sounded like a Bermudian, but like an Englishman with crude speech.

The pathologist who examined the complainant after the incident had concluded there was evidence of recent sexual intercourse, but no evidence of injury as a result. There was no evidence to suggest intercourse was voluntary or not, said Mr. Hollis. The pathologist said a lip injury sustained by the woman could have been the result of a misdirected kiss, and was not necessarily a bite.

[Mr. Hollis continued]

A Police officer had taken an impression of a footprint from the woman’s house, and compared it with Smith’s at the Police Station. The officer had tried to taken impressions in the bedroom, but the results were negative. He also tried around the windows, but there were no positive results.

On a comparison of foot impressions from the hallway with those taken from Smith at the Police station, the officer came to the conclusion in his expert opinion that they were the same.

Answering a question from the Bench, Mr. Hollis denied that the evidence tended to corroborate that the woman was raped by the appellant, but agreed that “it might be strong evidence” that he was in the house. Evidence was also brought that there was another man in the house.

“The evidence of the complainant was that although she identified him at the Police Station, she had also said that the man who assaulted her had a scar so noticeable that she pulled her hand away. Her evidence is so contradictory that it may be that it was not necessarily Mr. Smith who was the man in her bedroom,” said Mr. Hollis.

Smith himself had given evidence that there was no scar on him at all. Unchallenged evidence was given that Smith was stripped in the Police Station and no scar was found.

At the Police Station, the complainant had no chance to compare Smith with any other person at all. It was a face-to-face confrontation – so much so that it would appear to her that the Police thought that he was her assailant, said Mr. Hollis.

Mr. Hollis turned to the evidence which had been given during the trial be Chief Inspector Clive Donald. He said that the officer had been cross-examined as the correct identification procedure. Chief Insp. Donald had told the court that Smith refused to take part in either an identification parade or a street parade and eventually he was placed in a room by himself and there was a face-to-face confrontation between Smith and the complainant.

But, said Mr. Hollis, the identification procedure laid down said that if a person refused both of the formal alternatives – he should then be offered the choice of being placed in a room with a number of people or being placed in a room alone for a confrontation.

Mr. Hollis said it was put to Chief Insp. Donald that he should have followed the procedure and the officer had said it would have been difficult to find people of similar size and build to put in a room with Smith. Mr. Hollis said that Chief Insp. Donald had said it would have been fairer to Smith if he had been in a room with other during the identification.

The Court President, Sir Michael Hogan, said the procedure allowed for a confrontation to be arranged if putting the person in a room with others was refused or otherwise impractical.

Mr. Hollis said he disputed that it was not practical to put Smith in with others. He said he knew of two police officers who were of a similar description to Smith and that Chief Insp. Donald had a day in which to find suitable people to put in the room with Smith.

“If any men had been placed in the room with Smith it would still have been fairer that placing him in a room by himself. I am not making an attack on police procedure, but the way in which identification was carried out leads to some doubt being placed on the complainant’s evidence,” Mr. Hollis said.

Professor Georges asked Mr. Hollis what sort of an accent Smith had. Mr. Hollis replied that his client spoke with a very broad Bermudian accent.

“I am saying the identification was unfair,” said Mr. Hollis. “The identification evidence as given in court is not only doubtful but also inconsistent and completely conflicting in some regards.”

“He said that the complainant identified a scar on her assailant’s body. “This was a woman who said she was appalled that the man was in her house and yet in the middle of what she described as rape she feels a scar of such magnitude that she pulls awat from it. This is a striking point,” Mr. Hollis said.

For the jury to convict, they would have had to find that Smith was in the house on the evidence given and then go on to find that on the evidence it was he who raped her and took the purse.

Mr. Hollis said the judges might be satisfied that the footprint evidence did place Smith in the woman’s house.

“However, there were no footprints in the bedroom although the floor as similar to the floor in the hallway where prints were found,” said Mt. Hollis.

There was no footprint or fingerprint evidence to connect Smith with the purse, he said.

Professor Georges asked if Mr. Hollis doubted the entire credibility of the complainant’s story. “Yes, it has inconsistencies in it,” replied Mr. Hollis.

On the burglary charge, Mr. Hollis said the jury not only had to be satisfied that Smith was in the house, but also that he broke and entered the house and stole the 60 dollars from the purse. There was no forensic evidence to connect with the purse and the only evidence there was, was the footprint evidence of his being in the house and the woman’s identification.

“The evidence was so slight that conviction was unsafe,” said Mr. Hollis.

He said it was unusual for a rape case trial to involve an identification problem. It usually revolved around the issue of consent. He said he had to deal with the consent issue on the complainant’s evidence alone because Smith had no recollection of the evening. He remarked that the complainant had told the court that she had her arms around the person who raped her and that the woman refused to comment as to her sexual relationships with other men.

“He should not have been convicted on the evidence,” Mr. Hollis said.

On the question of the appeal against sentence, Mr. Hollis said that Smith had an extensive criminal record. He was given a period of corrective training when he was only 11 years old when he could not realize the consequence of his actions. Since that time Smith had only spent a total of two-and-a-half years outside protective custody, Mr. Hollis said. He could not read or write adequately and this hindered his progress and success in life.

Mr. Hollis said that various recommendations had been made by the courts for Smith to be given rehabilitative training but they had never been acted upon.

“We should not lock up Smith like a caged animal for a period of ten years and nothing be done at all. That is wrong and regressive; society should be able to deal with him in a constructive and not destructive manner,” Mr. Hollis said.

Asked what alternative sentences there were, Mr. Hollis said that at one time it might have been possible to send Smith to another part of the world to a place like Broadmoor where he would get the help he needed.

“On his behalf I could do no more than look to this court for some guidance as to how he could be dealt with,” Mr. Hollis said.

His submissions to the court were that the sentence far exceeded sentences given in the last seven years in Bermuda for rape; that having regard to the offence, the sentence was harsh and excessive, and that further, the sentence would have a destructive instead of constructive effect on Smith.

Mr. McMillan, for the Crown, said he would be brief in replying and would not comment on the matter of sentence. It seemed to be agreed that there was a man in the complainant’s house on the morning in question and that he had sexual intercourse with her. What was disputed was the identity of the man and the issue of consent.

He said the Crown relied primarily on three points of evidence: that the complainant did not consent to sexual intercourse, that she identified the man who had raped her and on the footprint evidence. He took the court through the evidence relating to these points.

Mr. McMillan said that Dr. Cunningham had told the jury that there had been recent sexual intercourse and that the complainant had sustained an injury to her lip, consistent with the evidence she had given to the court.

“I submit there was ample evidence on which to convict and it is not unreasonable for the jury to come to the conclusion they reached,” Mr. McMillan said.

The judges asked for counsel to supply them with details of the previous criminal records of people who had been jailed in the past few years for rape and counsel pledged to do so.

The Appeal Court judges said they would give their decision later.

The appellant has an unhappy history and seems in many ways to be incapable of meeting the problems presented by life but plainly the learned judge was right in recognizing that society needs to be protected and we think he was right in imposing a term of preventive detention but it seems to us that the period was longer than appropriate and we reduce it to seven years,” they decided.

The judges paid tribute to the way barrister Mr. Wendel Hollis, who represented Smith, presented his case.

“Despite the sterling effort made by Mr. Hollis on behalf of his client the appeal against conviction must be dismissed,” they ruled.

Smith was found guilty of raping a Southampton woman last August and robbing her of cash. He was identified by the victim at Hamilton Police Station. The judges said Mr. Hollis argued that the identification was not satisfactory, as, according to a memorandum circulated to the police by the Governor, the accused should not have been in the room alone and should have been accompanied by six others of similar type and build.

Mr. Robin McMillan, for the Crown, pointed out the accused had refused to take part in an ordinary identification parade or street identification and there would have been great difficulty in getting other men of the same type and build because of Smith’s “massive proportions”.

Mr. Hollis also urged that the victim claimed the rapist had a scar whilst Smith said he had no scar. The victim also said the rapist spoke with an English accent and Smith had not been out of Bermuda so Mr. Hollis claimed it was unlikely he had anything but a Bermudian’s accent.

“The matter of the scar was not explored in any depth at the trial,” said the judges. “In any event these were matters for the jury to weigh, consider and determine.”

They said the victim’s account of the rape was “entirely credible” and footsteps found in her house strongly supported her evidence.

“We can see no justification whatever for interfering with the verdict in this case,” they ruled.”

A series of seventeen burglaries and house break-ins over a two-night period in Paget parish alone had caused a “degree of panic in the community.”

Complainants in several cases had variously described the culprit as a “large, colored man, over six feet tall.”

The Acting Commissioner, Mr. Clive Donald said the Police knew full well who they were looking for – “suffice it to say that every Police officer in Bermuda has access to this man’s photograph and description, and his arrest is being given top priority. We have a large number of Police officers on extra patrols and we are searching for one particular individual,” he said.

Mr. Donald assured the public that Police were doing “everything in our power” to solve the crimes. “Detectives are working around the clock. Officers have been brought in from other departments of the force to augment both uniform and plain clothes patrols, and I am being kept fully abreast of all developments,” he said.

As a Detective Inspector then working out of Hamilton CID, I led teams of officers strategically concealed during the hours of darkness along the Railway Trail tracks from Grape Bay, Paget westward to Middle Road, Southampton.

At a time when the matter was being editorialized and discussed in Parliament, Smith was captured on March 15, 1984 after which court appearances ensued.

An additional EXPO article covering this episode in 1984 is anticipated in the near future.

_______________________________________________

16th May 2022

Young P.C. Ray Sousa

Young P.C. Ray Sousa

Ray Sousa's dealings with "Eggs" Smith

Ray served in the Bermuda Police from January 1966 - 18th May 1974, and had several encounters with Kennth James Maxwell "Eggs" Smith prior to the above case. Ray has written the following to us from his home in Australia which highlight just how difficult it was to deal with "Eggs" during his crime sprees.