CLICK HERE to read the history of the inauguration of the a fingerprint section in 1924

The end of the Second World War in 1945 brought about the rapid growth of air mail services throughout the globe and made possible the rapid exchange of fingerprints between police forces of one country and another. There were occasions however when even the speed of an aircraft was not rapid enough for the purposes of justice. This applied principally to the extreme distances such as between Great Britain and her more remote Antipodes in the South Pacific, and to a lesser degree between Great Britain and the Far East.

By January 1946, fingerprints, photographs and related descriptive matters were being successfully delivered by radio beam transmission on the same day they were dispatched. Without the aid of this radio fingerprint system of identification the subsequent detention and conviction of international criminals would have been virtually impossible.

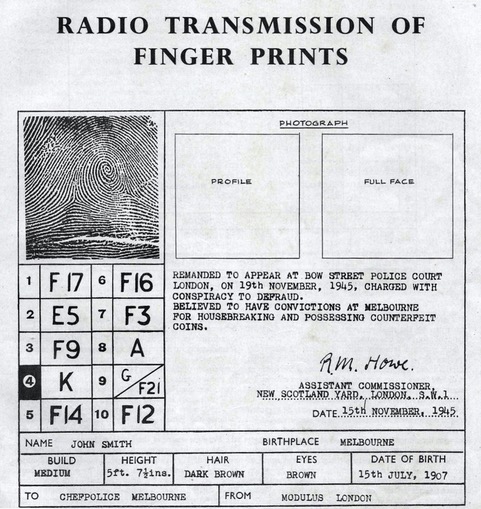

By the summer of 1949, after testing procedures had been researched and codes and standards adopted, photographic enlargements of prints for transmission purposes soon became the norm (always provided they had been properly taken) – with the prints thereafter being received in a decipherable state. The maximum size of the form for transmission was 10 x 9 inches for the British Empire and 7 x 5 inches for certain European countries but a more convenient size was later established at 7½ x 6½ inches.

1954

By 1954 Bermuda had become fully engaged in this new radio transmission event when the Island was quoted within the following book in which the notation “D/C 242 M. Willey, Bermuda Police” is seen in handwriting inside the front cover.

THE FINGERPRINT SYSTEM AT SCOTLAND YARD – by Frederick R. Cherrill M.B.E. formerly Chief Superintendent in Charge of the Fingerprint Bureau, Scotland Yard, London (1954)

“Within the British Empire, radio picture transmissions are exchanged over direct circuits between London and Montreal, Cape Town, Melbourne, Bombay, Colombo, Malta, Barbados, Bermuda, Nairobi, Wellington (New Zealand) and Salisbury (Rhodesia.) A one-way circuit from Singapore to London is also operated but at present is open for official pictures only.”

[This book is now in the possession of retired fingerprint expert Detective Inspector Keith Cassidy.]

The above Image shows one of the very early radio transmissions of a finger print from the London Metropolitan Police to the Melbourne Police, Australia on 15th November, 1945. In this case the numbers ‘1’ to ‘10’ in the two columns on the left hand side of the specimen transmission form immediately below the finger print indicate the digits of both hands – and this highlighted No. 4 is the right ring finger which references the coding cipher K meaning a whorl (outer ridge tracing).

The Bermuda Police gained a new impetus and a useful advantage over the lawbreaker when an additional specialized section was adopted in 1954 with the introduction into the force of forensic photography as a tool of law enforcement.

This article attempts to place on record much of what has occurred in Bermuda since September 1954 when, at the 39th annual conference of the International Association for Identification at the St. George Hotel, St. George's, a Mr. Harris B. Tuttle, of the sales division of Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, New York joined with Colonel Cecil Newing, Chief Superintendent and head of the Bermuda C.I.D. in announcing a collaborative effort to convict criminals.

Mr. Tuttle was speaking at Saturday's session of the conference as reported by the Royal Gazette (RG) on Monday, September 13th, 1954 when he said:

Mr. Tuttle was sure all would agree that cameras and photography played a major role in tracking down and convicting criminals today. The use of photography in law enforcement, he added, had made greater progress in the last ten years than it had in the previous 50.

Mr. Tuttle further declared:

“While wire photo devices were originally invented to send news pictures for use in newspapers they had found ready use in transmitting pictures of wanted criminals and their fingerprints from one state to another by telephone wires. This system was called the “speed photo" and could be used positively to identify a person within an hour.

With this device it was possible to "trigger" cameras or burglar alarms and then to make a still picture or motion picture or to sound the alarm without the intruder being aware of what was happening. This type of detector could be used with or without cameras and could be made to send an alarm signal to a night watchman, a police officer or fire department or any other receiver.

Motion pictures, continued Mr. Tuttle, were already playing an ever-increasing role in the law enforcement field. He believed it was only a matter of time when motion picture equipment would be a standard tool in every law enforcement agency.

A number of police departments are making movies of drunken drivers, and very successfully too, for now the arresting officer can have photographic evidence to back up his testimony," went on Mr. Tuttle.

The speaker said that to his knowledge such movies had been shown in court only on one occasion. It had resulted in a tremendous saving of court time and if used widely would produce a higher percentage of convictions.

The speaker also described how the Cleveland, Ohio, Police Department solved a number of thefts from parked cars by photography.

Mr. Tuttle said in the past few years awakening to the possibilities of colour photography in the law enforcement field had been very evident. "I’ve always believed that all evidence pictures for record purposes or for use in court should be made in colour," he continued.

Colour photography was just as easy and just as certain today as black and white photography. If the colour slide or movie was a reasonable record of the original subject as it appeared at the time it should be admissible as evidence, declared Mr. Tuttle.

Because of the non-arrival of two of the morning's scheduled speakers the afternoon's business was dealt with during the morning so that delegates could have the afternoon off to go shopping in Hamilton.

“Identification of people by finger, palm, toe and sole prints was accepted police and judicial procedure.

Epidermal ridge formations of the fingers, palms, toes and sole all formed the same anatomical and identification basis. Therefore anyone competent to make an identification in court was equally qualified to identify palm, toe and sole impressions.

Yet some courts would not qualify the competent fingerprint expert to identify impressions of palms, toes or soles unless he showed extensive study and experience with the three latter body areas.”

In an ‘off the cuff’ speech Inspector Thomas Dwyer, from Detroit, another unscheduled speaker, gave a general review of identification matters, mentioning some of the problems fingerprint men encountered and how they overcame them in Detroit. He also described the single fingerprint system which is only used in Detroit.

A number of delegates had attended Sunday morning service at ancient St. Peter's Church where their president, Mr. George A. Kanz, read the lesson. During the afternoon about 120 delegates and their families went on a sightseeing tour which included the Aquarium, the Caves, Devil's Hole and Kindley Airfield.

As was reported by the RG, on Tuesday, September 14, 1954 Colonel Newing said:

"I am sure we could become a much more efficient crime detection unit if we had laboratory equipment available to enable us to put into operation some of the scientific techniques which have been developed in recent years and in which many of the men here have been trained."

He said that on the whole the Police Force is badly housed and the C.I.D. is forced to work in a very cramped space.

Colonel Newing was addressing the conference of the International Association for Identification at the St. George Hotel.

On the conditions before and after motorization Colonel Newing said:

"Before 1946 there was little movement of people outside their own parishes, and the stranger was easily detected. A more intimate parochial life had its effect on the people. In those days the tempo of life was thus lower and Bermuda could rightly be called an island of rest."

Today, though there was a marked absence of really major crime, the police were troubled with hotel and beach thefts "and there is a great deal of petty larceny" he said.

In the majority of cases only money was stolen but the chances of ever finding the thief were very remote, though there was an instance this year where the precaution of a visitor in taking the serial number of a 20-dollar bill led to a conviction.

Because of the reluctance of local men to join the force, 70 per cent of the establishment of 138 were recruited from the United Kingdom. Facilities were available for the men to return there for various specialist courses in C.I.D. work, fingerprinting, photography and forensic science.

“But we do suffer from being so small a unit in as much as we cannot devote as much time and effort as we would like to professional training," said Colonel Newing.

The Bermuda Police Force, he pointed out puzzled visitors from America because of the absence of a display of guns. He liked to think that the Colony was "a little bit of England, full of English ways" – factors which made the police force here so different from the Colonial Police elsewhere in the British Commonwealth.

Absence of a military aspect among the police here was due to its history. There was no-one on the Islands when the first English settlers arrived.

Happily Bermuda escaped the military touch and as time went on its police force evolved and developed on English lines.

Visitors had commented on the apparent lack of guards for the Queen during her visit last year, he said. With respect, he was surprised by the difference in the methods taken to ensure the safety of the American President at the Big Three talks.

Actually in the case of the Queen she was very well looked after, though inconspicuously, said Colonel Newing.

The English police force, on which the Bermuda force was modelled, was something unique in that it had grown out of the individual citizen's responsibility for keeping the peace.

Every member of the police force here, regardless of rank, took three oaths as in England – the oath of allegiance; an official oath faithfully to serve the Queen; and a constable's oath in which he agreed to exercise his duties and power to the utmost letter of the law.

“His powers are clearly defined by law and he alone is responsible for the correctness of his actions. He must stand or fall by his interpretation of the law. No political party, in or out of office, can dictate to him, and, like the judiciary, he is independent of and entirely outside all politics," said Colonel Newing.

The acting senior magistrate the Wor L. M. Minty, in a talk entitled "Fingerprint evidence and other means of identification as accepted by British courts", referred to the ancient practice of the Japanese in taking thumb-prints as a means of identifying documents, and bridged the gap to early in the 19th century when a study of finger-prints was taken up in Europe.

Said the Wor Minty:

“Scotland Yard did not set up its finger-print section until 1900. Before that a system of measurements, drawn up by the head of the Paris Surete, was widely used. California early adopted a system of fingerprinting to cope with a Chinese problem.”

He did not think it was earlier than 1907 before the first conviction on finger-print evidence was registered in a British senior court.

Another speaker

Mr. E. J. Smith, of Chicago, the legal representative for the I.A.I., spoke on the legality of taking fingerprints under compulsion. He warned against the forcible taking of finger prints and photographs without proper authority, bearing in mind the right of an individual to be left alone and the right to go on living without being besmirched by a neighbour or some other person.

Some officers, where there were acquittals, stood the risk of involving themselves in civil actions for damages where prints and photographs had previously been taken.”

It should be noted here that some thirty years earlier in 1924 at the inauguration of the Fingerprint Section in the Bermuda Police Force the following photographic equipment had been obtained to assist in the presentation of the evidence before a court.

CLICK HERE to read in detail about the Inauguration of the fingerprint department in Bermuda in 1924

1955

“Opening the case for the Crown Mr. J. B. Pine, Solicitor-General, told the jury how an elderly lady sleeping alone in her home at Warwick awoke in the early hours of the morning to find a masked man standing by her bedside, and the events which followed, were described in the Supreme Court yesterday when the trial of George Quedel Theophilus Minors commenced before the Chief Justice, the Hon. Sir Trounsell Gilbert.

Minors is accused of breaking and entering the house of Mrs. Hilda Muriel Horsfield during the night of December 8/9 with intent to steal; of breaking and entering Mrs. Horsfield's house and stealing a wallet and two purses containing approximately £15; and of indecently assaulting Mrs. Horsfield.

“When the jury examined that cloth they might think it was the piece of cloth which Mrs. Horsfield saw over the head of the intruder. The Solicitor-General said the same day the accused's fingerprints were taken and had since been compared with the one on the window. Det. Sgt. J. W. Starbuck would say that he had found some 24 identical characteristics.

Evidence presented during the trial included that of P.c. Edgerton Carl Maybury who told of arresting the accused on December 16 [1954] and taking him to Police headquarters.

“Det. Con. James Christopher Patrick Hanlon testified to going to the home of Mrs. Horsfield with other police officers and searching for fingerprints. He found one on the inside of a bedroom window about half way up on the frame. He raised the print and it was photographed by Constable Waddell.

Evidence of photographing the fingerprint was given by Constable Waddell. He also spoke of finding the window screen lying on the ground. It was cut or torn.

The case resumed the following morning when extra copies were required by the court of photographic enlargements of the ‘prints.

As the science of forensic photography evolved during trials before Bermuda’s Supreme Court there arose interesting examples of case management challenges such as these reported below [in part]:

The first such case of this nature precipitated a trial adjournment in order that photographic copies of fingerprint enlargements could be hastily prepared and entered into evidence in order that the Court and jury might properly follow the evidence. This was the start of an expensive and time consuming operation.

As reported [in part] by the RG on Saturday, May 14, 1955

Detective Constable W. M. Smith testified to going to "Add-a-Bit" on April 13. He dusted the small cedar box with special powder and developed a latent fingerprint.

Detective Sergeant J. W. Starbuck said that on April 27 he took the fingerprints of the accused and compared them with the print on the cedar box. He was able to identify the print on the box as having been made by the left thumb of Campbell. Photographic enlargements revealed 17 characteristics in agreement.

The witness, in reply to Sir Trounsell, said there had not been time to prepare extra copies of the photographic enlargements of the prints. Sir Trounsell said it was desirable that he and the jury should have copies on which to follow the evidence as to characteristics. The case was then adjourned until Monday.”

“Inspector Stanley Riddell Moir, who was a detective-sergeant in the criminal investigation department at the time of the incident, said that at 8.30 a.m. on Thursday, December 10, 1953 he went to the Tea Cosy. The door of the cupboard on which stood the cash register had been split in the centre. He dusted the cupboard for fingerprints and found three latent finger marks, which he photographed. He handed the negative to Det. Sgt. Starbuck.

Answering Miss Browne, Inspector Moir agreed that the Tea Cosy had been broken into before and after this occasion in December, 1953. In reply to the judge, the inspector described the fingerprints which he found as being "fresh."

Detective-Sergeant John Wallace Starbuck, who was accepted by the court as an expert in fingerprint identification, testified that on December 10. 1953, he received a negative from Inspector Moir. He identified the fingerprints contained on the negative as having been made by the left index, middle and ring of accused. Comparing photographic enlargements he found a total of 45 characteristics in agreement – index finger 8, middle finger 22 (at least), ring finger 15.

Sgt. Starbuck said that on May 26 Davis made a statement in which he said he knew nothing about the offence. He had never been to the Tea Cosy and was sure that his fingerprints were not found in the restaurant.

Miss Browne: Did you have a record card of Daniel Charles Davis in your files in 1953?

Sgt. Starbuck: We did.

Miss Browne: Did you compare the prints on the negative with the prints of Davis then? – I did not.

Miss Browne: How is it that in 1955 when Davis's fingerprints are taken once again you compare them with the fingerprints found at the Tea Cosy?

-- Certain reasons which I cannot very well disclose to the court.

On the advice of the acting Chief Justice, Miss Browne did not pursue this line of questioning any further.

Detective constable William Maurice Smith gave evidence of arresting Davis on May 18 this year.

Without calling upon Mr. Barnard to reply, His Lordship said he was satisfied there was a prima facie case, particularly having regard to the statement made by accused that he had never been in the restaurant.

Evidence for the defence was extremely brief, Davis being the only witness. He said he was unable to recall December 9 or 10, 1953. He did not break into the Tea Cosy restaurant.

Mr. Barnard: Have you ever been in the Tea Cosy restaurant?

Davis: No sir.

Mr. Barnard: Can you give us an explanation of how similar prints to yours came to be found at the Tea Cosy on December 10, 1953?

Davis: No sir.

In his address to the jury, Mr. Barnard referred to authorities which said that fingerprint evidence alone was sufficient evidence upon which to convict. The only answer in this case, he continued, was that the fingerprints found in the Tea Cosy got there legitimately or innocently, but they had heard accused say that he had never been in the restaurant.

Miss Browne, in her speech to the jury, maintained that fingerprint evidence was not infallible. Although two people might not have fingerprints with all the characteristics similar they could have a few characteristics in agreement. The fact that the fingerprints had not been checked in 1953 aroused suspicion of the system of keeping fingerprints at the C.I.D.

In his charge to the jury, the judge said they might think there was ample evidence to lead them to the conclusion that there had been a breaking within the meaning of the Act, by way of opening a window, and there was ample evidence to come to the conclusion that someone did steal from the piggy-bank.

His Lordship invited the attention of the Jury to the categorical statement of Sgt. Starbuck that there were no dissimilarities between the prints found on the cupboard and prints of accused on the record card. On the left middle finger, discounting two characteristics which were in question, there were still 20 characteristics in agreement and that was substantially above the number laid down for positive identification. And there were the 15 characteristics in agreement on the ring finger and the eight on tile index finger.

The judge said the question of infallibility of fingerprints hinged upon experience over the last 50 years during which millions of prints had been taken and it appeared from records that no two persons had ever been found to have the same fingerprints.

"I would suggest that the evidence of Sgt. Starbuck was given extremely fairly, very clearly and was given from a wide knowledge and experience of the subject. I suggest one should pay great weight to his evidence in this case," continued His Lordship.

The acting Chief Justice, Major David Huxley, asked the foreman, Mr. H. C. D. Cox, whether it would be any good if the jury tried again to reach a verdict. The judge said it was of great importance that a jury should take all possible steps to come to a verdict, otherwise it would mean that the matter would have to be tried by another jury.

Mr. Cox replied that the jury had exercised the maximum "give and take" and he did not think it could come to a verdict.

The acting Chief Justice then dismissed the jury and remanded Davis in custody to await retrial. The case for the Crown was conducted by Mr. Ronald Barnard, who said that fingerprints were virtually the sole evidence put forward by the prosecution against Davis. Accused, who pleaded not guilty, was represented by Miss Lois Browne.”

[A re-trial of this case was commenced the following week when the RG of August 3, 1955 reported:

He repeated evidence he gave last week – when a jury could not agree on a verdict in Davis' case – that three impressions on a negative handed to him by Police Inspector S. R. Moir (a detective- sergeant in 1953) had 45 characteristics definitely identifying them with the fingerprint records of the accused.

He was cross-examined before the court on whether it was possible he could have been mistaken in matching the fingerprints of the accused and those on the negative which Inspector Moir obtained when he photographed a cupboard at the restaurant.

Sgt. Starbuck was positive he was not mistaken and mentioned the characteristics of a scar on one of the impressions. He was in the witness box for about an hour and a half.

Davis was remanded in custody by the acting Chief Justice, Major David Huxley, to await his third trial on the same charge.

In his address to the jury yesterday morning Major Huxley said the bare facts of the case were reasonably simple: during the night of December 9-10, 1953, someone broke and entered The Tea Cosy on Front Street, smashed open a piggy bank and stole about £1 in change.

A fingerprint was found on the door of a cabinet in which the bank was kept. Detective Sergeant John Starbuck said the print could have been made only by Davis: Davis denies ever being in The Tea Cosy.

Major Huxley felt the fingerprint evidence was of vital importance and would help the jury to come to their verdict.

After three and three-quarter hours of deliberation Mr. Edmund Zuill, foreman of the jury, reported they were unable to reach any verdict.

Major Huxley said it was very desirable that a verdict should be reached. Mr. Zuill said he felt it would be impossible to reach a verdict even if deliberations were resumed.

Mr. Ronald Barnard, who appeared for the prosecution, said he had been instructed by the Attorney General that the action would not be dropped and would be proceeded with at the earliest opportunity. Miss Lois Browne appeared for Davis.”

For the third time in as many weeks, the RG of Wednesday, August 10, 1955 reported as follows on the re-commencement of the Tea Cosy dishonesty case:

Two juries have already failed to agree on a verdict against Davis.

The prosecution's case depends entirely on fingerprint evidence. Yesterday, for the third time, Det. Sergeant J. W. Starbuck went patiently over enlarged fingerprint impressions which he claimed were those of the accused and compared them with a triple impression found on the door of a cupboard at the cafe by Inspector Stanley Moir (at the time a sergeant in the C.I.D.).

Det. Sgt. Starbuck, despite efforts by Miss Lois Browne (defending) to break down his evidence, remained steadfast in his view that the impressions found at the Tea Cosy were those of the accused.

Replying to Miss Browne the officer said the reason for the gap of some 19 months between the commission of the offence and the appearance of the accused in the dock charged in connection with it was that originally Davis was not suspected.

Normally in such a case the officer producing fingerprint evidence for him to examine (Sgt. Starbuck is in charge of this department of the C.I.D.) was asked if he suspected anyone. The records of suspected persons were then gone through.

Also studied, if necessary, were the records of persons known to commit a particular type of offence. There were 3,000 sets of fingerprint records at headquarters, embracing some 30,000 impressions.

Answering the acting Chief Justice (Major the Hon. David Huxley) who put questions based on information contained in a manual entitled "Modern Criminal Investigation" (produced by the defence), Sgt. Starbuck agreed that in the United States 12 characteristics in fingerprints were accepted for identity purposes.

This was the number which once applied here but the local police now used the number arrived at by New Scotland Yard – 16.

The officer stated he had made every allowance for error when studying the characteristics of accused's impressions with those found at the cafe.

Inspector Moir went into the box and repeated the evidence he had given at the two previous trials.

Replying to Miss Browne, he said there were other marks made by the person who had entered illegally, but he was "quite happy" with the impressions he obtained as these definitely pointed to the intruder.

The case for the prosecution is being conducted by Mr. Ronald Barnard, who has also prosecuted in the other instances.

This morning counsel for both sides will make their submissions to the jury and the acting Chief Justice will sum up.

No reference was made yesterday to the two other trials. A new jury was empanelled for the present case.

Davis, who yesterday again stated he could not remember what he was doing so long ago but was sure he had never had occasion to enter the Tea Cosy Restaurant for any purpose, did not object to any of the members.

Two previous juries in the present criminal session had been unable to agree upon a verdict.

Yesterday the jury took just over two-and-a-quarter hours to reach a majority decision as to Davis's innocence. This did not mean, however, that Davis was a free man for earlier in the session he had pleaded guilty to breaking and entering the Seaview Restaurant, Devonshire, and stealing approximately $55 in American currency, the property of Manuel Marirea and Masters Ltd.

The acting Chief Justice, Major David Huxley, discharged Davis on the Tea Cosy charge, but remanded him in custody to come up for sentence on the charge to which he had pleaded guilty. The judge said he would like a probation officer's report.

Police Superintendent Percy Miller said that Davis was first convicted in May, 1948 for forging and uttering a document. In February, 1949, he was convicted for receiving an auto-bicycle; in July, 1949, for attempted stealing; in April, 1950, for stealing; in June, 1950, for unlawful carnal knowledge; in August, 1952, for common assault and in February, 1954, for receiving an auto-bicycle and for an insurance offence. He had served short terms of imprisonment.

Davis, a 23-year-old labourer of Middletown, Pembroke, was represented by Miss Lois Browne. Mr. Ronald Barnard prosecuted for the Crown on the Tea Cosy charge.

The acting Solicitor General Captain J. S. Cowie, appeared to prosecute in the Seaview Restaurant case.

The hearing of the Tea Cosy charge resumed with speeches to the jury by Crown and defence counsel. Addressing the jury, Mr. Barnard said the only evidence the prosecution could offer [was] that Davis was the person concerned was fingerprint evidence (sic).

Detective Sergeant J. W. Starbuck, he said, had told the court he was positive the latent prints found at the scene could only have been made by Davis. Sgt. the court as an expert witness (sic).

Fingerprints, continued Mr. Barnard, were used every day in a great many ways as a method of identification and that method was considered to be positive and reliable. It had been accepted in British courts since 1903. Sgt. Starbuck had termed fingerprint identification as infallible and the occasion had not yet arisen of two people having the same fingerprints.

There was nothing to say, continued Miss Browne, that although there were no two fingerprints alike there might not possibly be many fingerprints with a number of characteristics the same. This point, she suggested, should raise doubt in the minds of the jurors.

In his charge to the jury, the judge said the defence had made the point that blurred impressions found at the restaurant had not been photographed as well as the three other latent prints. He could see no force in that argument. The smeared impressions would have been virtually of no use in identification.

Major Huxley said there was very strong evidence that there had been a breaking, an entry and a stealing at the Tea Cosy. The case turned upon the value to be placed upon the three latent impressions found on the door of a cabinet.

If the jury reached the conclusion that the prints were those of the accused, there could be no question that they got there innocently because Davis had said on oath that he had never been into the Tea Cosy.

The judge went on to point out that, in the 50 years the fingerprint system had been used in practically every civilized country in the world, millions and millions and millions of prints had been taken yet there had never been found any case in which two people were shown to have similar prints.

Detective Sergeant Starbuck had said that fingerprints of a person never changed although they could be affected by scars, etc. As an expert, the sergeant had not only spoken of his beliefs, but had produced various photographs for comparison and had taken the court through the various stages which had led him to come to his conclusion as an expert.

He thought there had been some misconception as to the number of characteristics because, as he understood Sgt. Starbuck, that was only half the matter. It was not only a question of the number of characteristics, but the pattern and sequence in which these characteristics were situated. The possibilities of the pattern, a complex one, being alike were infinitely less.

Sgt. Starbuck had said there was no point of true dissimilarity as to the basic characteristics, sequence, order or pattern of the prints before the court. The defence had suggested it was unfortunate that other parts of the finger had not been placed on the record card. Sgt. Starbuck's answer to that had been that there was ample and overwhelming evidence without going any further.

The defence had suggested that fingerprint identification was by no means infallible while the prosecution maintained that it was a well-tested means of establishing a person's identity.

The judge thought it only fair to say that the evidence of Sgt. Starbuck had been given very clearly, very fairly and very convincingly. There was ample evidence on which the jury could convict, but the jurors were the sole judges of fact.

The jury comprised Messrs.………………..

The court was adjourned until the following day (Friday) when sentencing would be carried out.

“Daniel Charles Davis (23) was sent to prison for two years for breaking and entering the Seaview Restaurant, Devonshire, and stealing $55 American currency – a charge to which he had pleaded guilty.

Mr. Harry Osborn (probation officer) reported that Davis had a common-law wife. He was of retarded intelligence and was likely to become an habitual offender unless checked. He had a low moral standard.

Major Huxley said Davis had not got a good record over the last seven years. He had a string of convictions, mostly for minor or moderate dishonesty. That dishonesty had got to stop.”

1957

Exactly two years later on Friday, July 26, 1957 in another Supreme Court trial, the RG reported as follows:

“The owner of a suitcase alleged by the police to have been the one used in the Somerset robbery denied in the Supreme Court yesterday that it was the actual case borrowed from him by his brother-in-law, Junior McDonald Webb.

Webb has already pleaded guilty to robbing the Somerset branch of the Bank of Bermuda of £10,110 on May 14 [1957] and has been sentenced to five years imprisonment.

The other two defendants, who have pleaded not guilty, are Robert Leroy Green and Llewellyn Talbot. Green is represented by Mr. Arnold Francis and Mr. E. A. Jones Talbot is represented by Miss Lois Browne. The Solicitor General, Mr. Hector Barcilon, is prosecuting and the case is being heard by the Assistant Chief Justice, Sir Allan Smith and a jury.

The owner of the case, Hilgrove Jones, told a crowded court on the fourth day of the trial that Webb had, in fact, borrowed a suitcase from him around the time of the robbery, but it had never been returned”.

Most of yesterday's hearing was again taken up by detailed cross-examination of two police witnesses by Mr. Francis and Miss Browne. In particular, they exhaustively questioned Colonel Newing and Inspector John Starbuck

First witness to enter the box yesterday morning when the Crown resumed its case was P.c. Westmore Smith Bean, who was on duty at Somerset police station on the afternoon of the robbery May 14. Bean said he received a phone call at about 4.20 p.m. A man who did not give his name said the Somerset bank had been robbed. Then the caller hung up.

P.c. Bean said he got into the bank through a door at the back. The place seemed empty but he noticed a bullet on the floor. He identified it as being similar to one shown him in court. He heard voices coming from the vault and returned to the station to fetch Sgt. Ball.

PC Westmore Smith Bean

PC Westmore Smith Bean

Next witness to be called was Inspector John Wallace Starbuck, who spent an hour-and-a-half in the box. He said that following the robbery he was given a sheet of Perspex from a table in the bank which had been tested for fingerprints. He found a fragmentary palm impression and photographed it.

On May 28 he saw Green at Hamilton police station and took an impression of both his palms. He later re-took the right hand impression as he wanted a more extensive print of the side of the palm below the little finger.

He compared this print with the Perspex impression and positively identified it as having been made by part of Green’s right-hand palm.

In addition there were no dissimilarities in the two prints, which increased certainty of identification.

Starbuck said he had been working on fingerprints since 1942 and had received a diploma for this work. He had also attended a course at Scotland Yard in 1951.

In cross-examination, Mr. Francis asked if it wasn't a practice to show more matching characteristics than the minimum number of 16.

Starbuck replied that there was no point in marking off more than 16.

Mr. Francis asked: "Have you ever shown more than 16 in court?"

Starbuck: "Before taking the course in England I did."

Counsel then went into detailed examination of the individual characteristics marked by Starbuck as being similar, and queried several of them on enlarged photographs provided [to] the jury and the counsel. Starbuck pointed out that one was an ink impression and the other a sweat and powder impression.

Mr. Francis wondered whether the print would not have dried out had it been merely a sweat impression. The inspector said the print was "raised" the same evening and photographed the next day.

Starbuck replied that they were [an] equally positive means of identification.

"Was there anything unusual in Green's print?" asked Mr. Francis.

When the witness replied: "No," he asked if identification was not "on surer ground" when the print showed any unusual features.

"No," said Starbuck "it makes positive identification much quicker but not surer."

Re-examined by Mr. Barcilon, Starbuck said lack of moisture would only affect the clarity of a print, not the shape of characteristics.

Starbuck added that there was no universal system of classifying palm prints but there was in the case of fingerprints. That was why palm prints were not so popularly used.

Adding that he did not want to deprive the jury of – "the enjoyment of playing amateur detective," Mr. Barcilon next went into detail on the photographs of the two prints and pointed out more similarities not marked by the inspector.

Col. C. J. R. Newing, Chief Superintendent of the C.I.D. was the day's third witness. He told of receiving information on May 26 from Raymond Young, the driver of the taxi used in the robbery, which led to the arrest of Webb.

“Newing said he visited the bank on May 15 with about a dozen photographs of various suspects drawn from C.I.D. records. He had shown them to the bank staff and nobody had picked out any photograph.

On June 11, the witness added, he had taken to the bank another completely different batch of photographs, including those of the three accused. This time, one of the bank employees, Mrs. Mayfield, picked out Talbot.

Green, whose palm print the prosecution maintains was found on a desk top at the bank, testified on Monday that Inspector John Starbuck took his prints four different times at police headquarters. The last time Green said: "You people must like my print. Is this what you always do?"

He said Starbuck said: "Well, yes. We try to get enough.

A few days later, he said, he was told by Col. C.J.R. Newing (C.I.D. superintendent) that police had found his palm print at the scene.

“I told him it was impossible,” said Green.

“As for the palm print found at the bank and identified as Green's, Mr. Francis said there was "nothing sacrosanct" about the opinion of an expert. It would be up to the jury to decide if it were really Green's. He said it was interesting that it was not known whether Inspector Starbuck also took prints of all the bank staff in order to eliminate them as possibly having left the print.

She told the jury to treat the bank robbery as they would treat any other robbery. Miss Browne harked back to Sir Allan having called Webb a "dirty little rat." This occurred after Webb's testimony that Green and Talbot were not his companions during the robbery, despite his earlier statement to police.

Is Webb a liar, or a dirty liar or rat?" she asked.

"I say if he was a dirty liar or a rat in the box he was a dirty liar or rat in his statement to police, and that you should dismiss everything he said."

She questioned the weight that could be given the fact that Mrs. Mayfield had picked a photograph of [her client] Talbot from 11 others as being one of the men who robbed the bank.

Miss Browne said two other employees had closer looks and a better opportunity to identify him but had been unable to do so.

“Dealing with identification by photographs, Sir Allan reminded jurors that one of the bank's staff, Mayfield, was first shown by police about 12 pictures of men, none of which was of the two accused.

Mayfield had not picked any of them as similar to the man who confronted her in the bank. Later, she was shown a different set of pictures, including those of the three suspects. She picked out the picture of Talbot as the man she saw in the bank. "It was more like an identification parade," said the judge.

The judge reminded the jury that:

Green's palm print taken by police and the palm print raised from the table at the bank were identical in many characteristics, apart from the 16 pointed out by the police. Sir Allan said he could not see any difference between the two prints.

A slight murmur in the public gallery of the Supreme Court greeted the "Not guilty" verdict returned by the jury in the Somerset bank robbery case on Saturday. A court attendant immediately silenced the noise.

Acquitted were Robert Leroy Green and Llewellyn Talbot, charged with the armed robbery of the Somerset branch of the Bank of Bermuda on May 14, [1957].

When the unanimous verdict was read out Sir Allan Smith, the acting Chief Justice, said in a quiet voice:

"Gentlemen, you surprise me. However, that is another matter. I hope the result of this verdict will not be such that we will get more crimes of this nature.

Sir Allan had stood up and was about to leave the court when the Registrar, Lieut.-Colonel W. T. Angelo-Thomson, drew his attention to Green and Talbot, who were still in the prisoners' dock with a warder.

"Yes, of course, the prisoners are discharged," Sir Allan said before leaving the bench.

Proposed Search For 'Joe' And 'Harry'

"I expect we will have to search for 'Joe' and 'Harry' now, since the verdict," Colonel Cecil Newing, Chief Superintendent of Police in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department, said yesterday.

[Joe" and "Harry" had been mentioned by Junior McDonald Webb during the Somerset bank robbery trial as being Webb's confederates in the armed robbery].

Col. Newing said the police would like to know if any of the money stolen from the bank has been found. He asked that the serial numbers of the notes again be published.

[Accordingly, the serial numbers of the new Bermuda bank notes stolen in the robbery were published forthwith].

A RARE AND UNUSUAL PRESS PHOTOGRAPH IS PRESENTED BELOW

1967

Three separate points of origin were observed, one in the Criminal Records Office (CRO); another in the central entrance hallway and main staircase leading to the upper landing area and another involving a cardboard box and its contents located in the toilet adjoining the porch on the southern side of the reception hall.

The considerable damage caused necessitated the evacuation of all offices within Headquarters building to vacant rooms in Bettington and McBeath blocks.

Early investigations identified the strong possibility that arson had been the cause and a hastily convened Inquisition under the Coroner’s Act, 1938 was opened and adjourned on the same day with nine named jurors having been – “duly sworn to inquire for our Lady the Queen as to the circumstances surrounding a fire at the Headquarters of the Bermuda Police Force, Prospect on the 13th day of March, 1967.”

In the following photograph ‘A’ two seats of fire are immediately evident, that is –

1) The ground floor CID / CRO offices to the left and

2) The central entrance hall and staircase leading to the second floor landing.

Photo ‘A’ (front of Police Headquarters) by DC Raymond Hodges

Photo ‘A’ (front of Police Headquarters) by DC Raymond Hodges

At the Coroner’s Inquest then police photographer Raymond Edward Hodges introduced an album containing 12 scenes of crime photographs each of which he described in a deposition recorded in handwriting by the Coroner Mr. Walter Maddocks and which reads (in part) as follows –

“I am a D/C in the Bda Police Force attached to Fingerprint & Photo Dept. at Police HQ Prospect.

“On Monday 13/3/67 @ 8.0 am I went to Police HQ and took a number of photographs … ... …at Hamilton Fire Stn. I developed the film and from the unretouched negatives I made photographic enlargements which I now produce and enter in evidence Ex. 1.

Photo A. Shows N. side of Police HQ

Photo B. Shows doorway into C.I.D. Offices to left of ….. in photo A.

Photo C. Shows close up of lock in door shown in photo B.

Photo D. Shows close up of bottom of same door.

Photo E. Shows interior of C.R. Offices …. burn to the back of door shown in photo B.

Photo F. Shows entrance to Police H.Q.

It should be noted that Willie’s Personnel Register records that he was an Aide to Hamilton CID between the dates 1 Feb 1969 – 16 November 1969 – a likely error in the year stated?

CLICK HERE: to read more of the evidence presented at the Coroner’s Inquest into the fire together with an eleven additional photographs and depositions describing in their own words the actions taken at the scene by individual police and fire officers to preserve the criminal records from instant loss. [forthcoming article]

The following police and fire officers were deposed before the Inquest in which they described their actions at the scene on that fateful morning –

Police Officers

Fire Officers

Civilian witness [residing at Camp Lodge, Prospect]

Mrs. Rosina Harriet Maude Greenslade

In the immediate term however, the CRO was relocated on a temporary basis to a fabricated building behind HQ – until it was found a more permanent location in Henderson Block, where it was joined after May 1982 by the Fingerprint section – which had, until then, been housed in the outer extension office of the Laboratory situated at the western end of the HQ building at ground level.

When this later move was made the area in the Laboratory once occupied by fingerprint officers DS Willey and DS Cassidy was reconfigured into individual ‘cages’ (built by then photographer Roddy Barclay) for use by SOCO personnel for the secure storage of their exhibits.

The CRO is where Civilian record keeper Verbena Daniels, DC’s Brian Callaghan (INTERPOL desk) and Andy Hall worked. Photographer DC Roddy Barclay recalls that he and Andy Hall laid the concrete pavers which led to the CRO door on the northern side of Henderson Block.

Meanwhile, SOCO was to remain in newly renovated premises in the lower left offices of the HQ building while a laboratory of sorts (LABSOC) was located in the extreme right of the HQ lower landing and used for firearm storage, a bullet making machine, and a fumigation chamber (constructed by Roddy Barclay).

1974

CLICK HERE to read the many ‘firsts’ achieved during the visit to a British Colony by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Musical Ride in 1968.

DC Roddy Barclay has put forward a couple of theories on how the use of colour photography may have occurred to capture the Mounties’ visit to the Island in 1968.

Option 1: The photo was taken on colour film by a BPS photographer with the film then being processed and printed in a colour laboratory elsewhere.

Option 2: The photo was taken by an independent local photographer on behalf of the BPS or through a news media such as the Royal Gazette.

Also, the Equestrian Association may have been involved in recording this scene since it was such a special event.

Retired Detective Sergeant Ernie McCreight recalls that black and white photography was still in use when he commenced photographic work at SOCO in November 1975 and that there was a soft transition into the use of colour as it gathered prominence throughout 1976.

DC Barclay remembers that the photographic chemicals and related equipment used by the forensic photographers at SOCO – initially led by DS Paul Farrell – were imported into Bermuda from KODAK USA through the courtesy of Stuart’s Camera Store on Reid Street, Hamilton.

1975

[I personally recall a related matter during a Bermuda Supreme Court trial in about 1976 involving a man charged with wounding with intent to commit grievous bodily harm to another.

On this occasion the accused was represented by Ms. Lois Browne-Evans who objected to the Crown’s use of coloured photographs in a police album about to be entered into evidence before the jury. She argued that the severity of the wound – as shown in colour – would be prejudicial to her client and had no probative value distinct from black and white photography. Her argument was overruled by the presiding judge …who may have been Justice Barcilon CBE].

Most often housed in a forensic lab, these professionals have two main goals: to identify evidence and to link individuals, objects, and locations through that evidence. Criminalists sometimes specialize in specific areas of physical evidence, some of which require additional training, they include:

- Firearms (forensic ballistics).

- Tool marks and mechanical fits.

- DNA

- Fire and explosion debris.

- Controlled substances and their identification.

- Trace evidence.

- Wildlife

According to Professor Ismail M. Sebetan, a forensic pathologist and director of the National University’s (NU) forensic sciences program, crime scene investigation entails the collection and examination of evidence at crime scenes. Evidence collected includes fingerprints, hair, fiber, or DNA, which are then taken to a crime laboratory for analysis. NU’s crime scene investigator training teaches students about the various types of evidence they might encounter in the field.

“Students learn about the types of evidence they are going to look for, and then about all aspects of detection, collection, identification, transportation, and how to keep the chain of custody until they hand off the evidence to the crime or forensics laboratory for analysis,” he says.

Crime scene investigators are also tasked with securing the crime scene, maintaining equipment, writing detailed reports, and testifying to their findings in court.

Professor Vanessa Schlottmann Calderon, a former crime scene investigator for the Pasadena Police Department and past instructor in the forensic sciences program at the National University (NU) describes it best when she explains that a crime scene investigator processes the crime scene by recording video, taking photos, collecting evidence, and sketching notes. “It’s almost like you’re putting the pieces of a puzzle together,” she says.

Crime scene investigators are also tasked with securing the crime scene, maintaining equipment, writing detailed reports, and testifying to their findings in court.

Professor Calderon cautions that crime scene investigation is not for everyone due to the irregular work hours as well as having to deal with horrific crimes on a daily basis. After every crime scene is processed, it’s standard practice to hold a debriefing with detectives, police officers, and other law enforcement personnel. “There’s usually a therapist or psychologist on hand to deal with any emotions that came up during the processing of the crime scene,” Calderon says.

“But outside of that, you have to have thick skin. You have to learn to desensitize very quickly if you really want to stay in this career. Crime scene investigators should be adaptable as they never know what a given day might bring. They are often called to crime scenes in the middle of the night or on holidays, which can eventually take a toll. Calderon says technicians need to be able to work in different environmental conditions, both inside and outside, at different times of day. They might be working in the rain or need to crawl into tight spaces to collect evidence.”

She adds that the job also requires an ability to work with other law enforcement professionals, such as detectives and coroners, as well as to interact professionally with victims, suspects, and witnesses. “Crime scene investigation requires a collaborative approach,” Calderon says.

Calderon explains that there’s a huge responsibility that comes with being a crime scene investigator. Not only are they tasked with properly handling evidence and maintaining chain of custody, but they are also expected to testify in court.

“There is a lot of weight on your shoulders because if you make an erroneous identification or an erroneous testimony, that could cost you your career,” Calderon says.

As a result, the profession requires good organization skills. “You really have to be meticulous and pay close attention to detail, gather as much evidence as possible, and look for anything that looks like a red flag or doesn’t make sense. Essentially, you’re processing a crime scene to be able to find guilt or innocence,” Calderon says.

She explains that crime scene investigators need to be comfortable and confident with public speaking as they will often be called to testify in court. They might be subpoenaed by either the prosecution or the defense. Calderon was often put on the stand as an expert witness. “It’s our job to remain impartial, factual, and straightforward,” she says.

“You can’t be afraid of being on what I call the hot seat, which is the testimony chair. You have to be able to deal with hostile environments, people, or approaches,” she continues.

“Attorneys can be very aggressive on the stand, so you have to be able to deal with the types of situations where not everybody likes you. For some people, you are a hero, but for others, they know that you are going to help put them away.”

For Calderon, playing a part in seeking justice for victims of crimes was an important reason she did the job. “For me, the most rewarding part of being a crime scene investigator was definitely finding justice for the victims or the victim’s family,” she says.

“There is relief in seeing somebody being held accountable. We don’t have control over the outcome of cases, but my work allowed for resolution and some sort of peace for the families of the victims.”

CLICK HERE To learn more about crime scene search and forensic science certification

Det. Officer Charles Edward Simons was also selected for overseas training course in Fingerprints in November 1924, served 1905 – 1935.

In 1934 then Constables [George] Smith and [Percy] Miller, were sent to New Scotland Yard for a refresher course on fingerprint identification.

CLICK HERE To see a – ‘photograph of photographers’

CLICK HERE: To read about Aideen Fletcher who served between1969-1997 Roger, (photos need to be centered on this link)

Ernie explained:

“I always had an interest in photography and with Peter Clemmet who had moved to SOCO the interest grew until I was developing and printing black and white pictures from home.

When Peter left to return to England I applied for the vacant photography position. A few weeks later I was in the yard at Traffic Department when Chief Inspector Derek Taylor call out to me, "Hey Mac, where do you want to work?"

"SOCO"

"Start Monday at 9 o'clock".

"Yesssssss". That was October 1975.

“In the mid-seventies there was very little photographic education available. Unlike now where everything you want to know about the subject is on You Tube. I found crime scene photography to be fairly straightforward. Touch nothing, move nothing and just light and record everything in sharp focus from front to back, and have a strong constitution. So once you knew what your flash exposures were it was easy. Night shots were a little more complicated illuminating long stretches of road in road accidents

“I wanted to learn and be a good confident photographer, knowledgeable to handle any assignment so over a three years period I paid for eleven week long courses covering various photography subjects at The Winona School of Professional Photography in the States.”

CLICK HERE to read more about Ernie’s 50 years in Bermuda in our "Then and Now" colum.

1973

1976 - 1977

OF COURSE IT’S A COURSE

Front row: Cherie Butler/Bean, Wayne Perinchief,

Steve Smedley is the young man top left and he kindly provided the photo of this course held in either late summer 1976 or the spring of '77. He was on the Marine Section at the time and attended this Scenes of Crime Officers course.

Steve says, “The object of the exercise was to train us to assess scenes to determine the necessity for the attendance of HQ Ident services. We were taught fingerprint classification, latent print lifting, photography (including developing and printing), exhibit preservation and a variety of other techniques that we were authorized to employ at the scenes of minor incidents (thefts, prowlers, etc.). When necessary, we were to call upon the REAL pros, of course! We were given all the necessary tools and equipment. I suspect that, while there may have been some successes, it was more an exercise in PR than anything else. Complainants expected the police to do something, so having us Divisional types take a few photos, and search for physical evidence, satisfied that need.”

Steve added, “I think that it was a two-week course and the knowledge that I gained was very useful to me throughout my forty-one year police career. I've occasionally wondered whether the program itself was particularly successful.

Editors note - Many thanks to Steve for supplying both the photo and this very clear description of the course. I for one had never heard of the course so I wonder how many other classes were held. Does anyone know? We have listed the names of those present in the caption. As is often the case, Davie Kerr came up with most of the names. Many thanks Davie.

CLICK HERE to read Steve Smedley’s article – "OF COURSE IT’S A COURSE"

1981

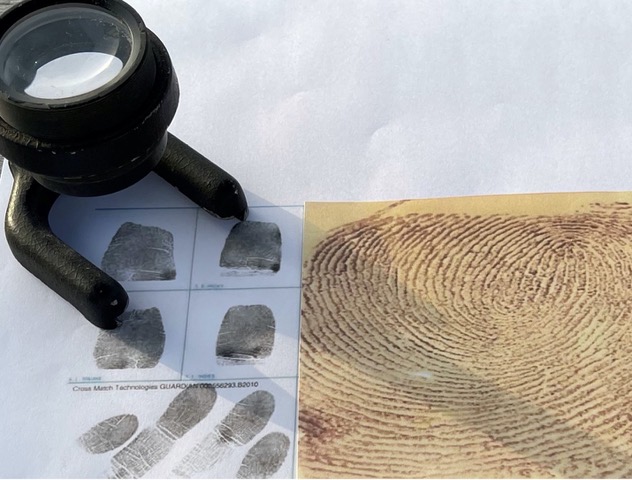

In the digital world of today, this style of glass is now used for training purposes and for single digit classification.

1982

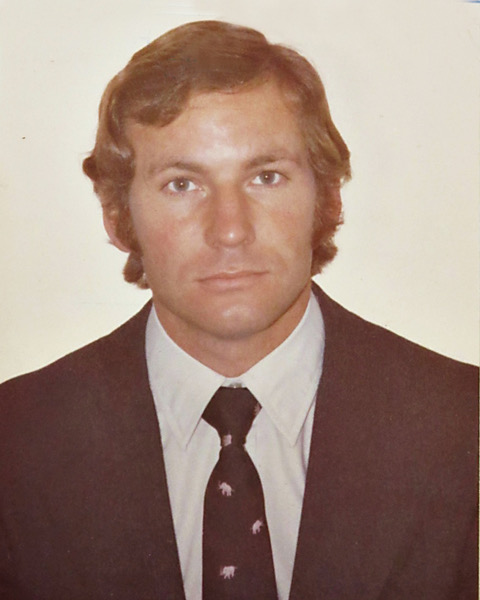

Fingerprint expert

Fingerprint expert

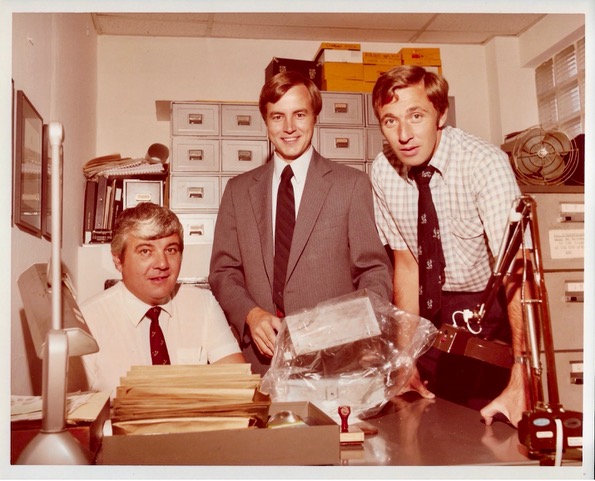

Forensic photographer

Forensic photographer Circa 1983

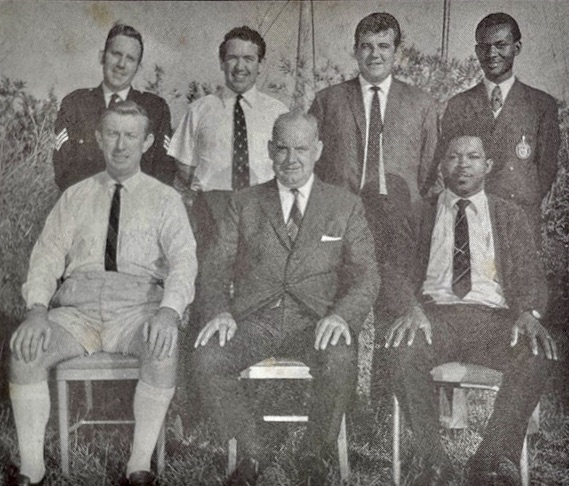

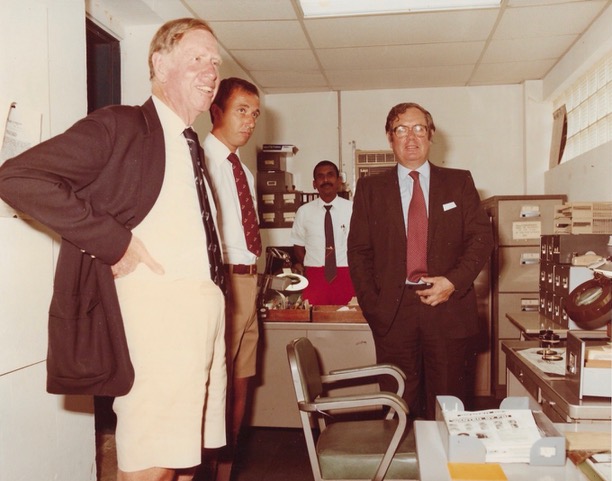

Official Visit to Fingerprint Department at Police HQ, Prospect

Official Visit to Fingerprint Department at Police HQ, Prospect1984

Later in this year of 1984, Det. Sgt. Keith Cassidy penned an article for the Winter editon of The Bermuda Police Magazine. Published in December of that year the article was entitled ‘The Bermuda Police Fingerprint Dept.’ and it covered the period from 1924 – 1984. Although the article essentially dealt with the then known history of the fingerprint department it also spoke to the other multi-disciplinary sciences and allied matters which included Photography and Criminal Records.

The article is reproduced as follows:-

This year, 1984, sees the Fingerprint Department and Scenes of Crime Office celebrate sixty years of service to the Bermuda Police. A brief history of the development of the Department is presented below: –

1924… In May the Governor, Sir Joseph John Asser and the Chief of Police, Mr. Sempill, entered into correspondence about the introduction of fingerprinting in Bermuda. Mr. Sempill had received training in the subject some twelve years eralier, at New Scotland Yard, and was keen to introduce the system to Bermuda. Further talks with Government led to Mr. Sempill going to New York in September to receive instruction in the latest methods of fingerprinting.

Two other officers, Inspector W.N.T. Williams and Detective Officer Simons left Bermuda in November for New York, where they received training. They retunred in December, accompanied by an officer of the New York Police Fingerprint Bureau, who came to assist in the setting up of the local fingerprint bureau.

On December 19th, Inspector Williams and Detective Simons went to Hamilton Gaol and fingerprinted and photographed twenty-five prisoners. The man with the distinction of being the first to be fingerprinted was a nineteen year old man by the name of Layman Selwyn Wallyn, who was serving a four year term of imprisonment for shop-breaking with an additional five and a half years for escaping from a prison work party and committing three further offences of house-breaking.

1926… In November, Mr. Sempill wrote to the Governor to tell him of the third conviction by means of fingerprints in the Island. Unlike the first two, in this one the Police had relied entirely on the identification of fingerprints left at the scene.

1934… Two officers, Constables Smith and Miller [Percy], were sent to New Scotland Yard for a refresher course on fingerprint identification.

1936… Superintedent McBeath attended the New York Police Fingerprint Bureau for a two month course on fingerprint identification.

1939… During this year three identifications were made from fingerprints left at the scenes of crimes. The total number of fingerprints in the collection now numbered 973.

1941… The fingerprint collection now exceeded one thousand sets. However, only one identification was made from prints at crime scenes.

1944… The Commissioner of Police, Mr. McBeath, went to New York and studdied the Battley System of classifying and filing fingerprints and the system was started in Bermuda the same year.

1949… The number of sets of fingerprints on file was now 1655, with 800 sets classified under the Battley System. During the year sixteen cases were brought to a successful conclusion by fingerprint evidence, a record number of identifications for the Department. The cases were split up as follows: – one shopbreaking, thirteen burglary of houses, one in the theft by stripping of a motor vehicle and one in handbag snatching.

1951… The taking of palm prints was commenced during this year, and of the nine cases solved during the year, one was by a palmprint.

1953… It was reported that evidence of fingerprint identification was given in court on three occasions during this year and that in one case the accused was acquitted even though his fingerprints were identified as being at the scene of the crime.

The total establishment of the C.I.D. at this time was one Chief Superintendent, one Detective Inspector, three Detective Sergeants, and five Detective Constables. All members of the C.I.D. were involved in the taking of fingerprints and the examination of crime scenes along with their other duties.

1958…After a re-organisation of the C.I.D., the strength of the Fingerprint Department, which also included Photography and Criminal Records was one Inspector, one Sergeant and two Constables. A total of 2,398 sets of fingerprints were now on file, and the palmprint collection now consisted of 552 sets.

1963… A small Police Laboratory was started, staffed by Sergeant Waddell, which assisted in the investigation of forging and uttering, traffic accident investigations and othe forensic examinations.

1965… Mr. William Sherwood arrived in Bermuda on a three-year secondment after retiring from New Scotland Yard, where he served for over 25 years in the Fingerprint Department and re-organised the operational side with his knowledge and by the introduction of new equipment. The number of identifications made during the year was 27 as opposed to only 4 in the previous year.

During the year 111 officers were given instruction in the taking of fingerprints and eighteen received instruction in searching for fingerprints at scenes of crimes. Inspector Christopher, the present officer in charge of the Department, began working in the Department.

1974… This year saw the introduction of the first Policewoman into the Fingerprint Department, Constable Aideen Fletcher, where she is still employed. Also joining the Department was the present Sergeant-in-charge, Keith Cassidy. After initial training locally, these two officers received training at the Fingerprint Bureau of the West Yorkshire Police, England.

During the year there were 628 examinations of scenes from which 70 identifications were made.

1977… This year saw the Department make 100 identifications from 820 fingerprint examinations. During the year a new single Fingerprint Collection had become operational. This system greatly reduced the length of time spent of searching the fingerprint collection, which now contained 7,605 sets of fingerprints and 4,398 sets of palmprints. Also introduced that year were Divisional Scenes of Crime Officers; uniform officers attached to each watch in the Eastern and Western Divisions were trained locally in crime scene examinations.

1981… During the year a new record in the number of identifications made during one year was set when 213 identifications were made from 1,255 examinations, (the number of examinations was also the highest ever for one year).

1982… The 10,000th set of fingerprints was taken during this year.

1984… This year the following personnel made up the staff of the Department:

Inspector Calvin Chistopher; Sergeants Keith Cassidy, (Fingerprints) and Ernest McCreight, (Photography); Constables Graham Alderson, Theodore Providence, and Howard Cutts (Scenes of Crime Officers); Constable Roderick Barclay, (Photography); and Constables Aideen Fletcher and Ashmead Ali, (Fingerprints).

The Department has undergone many changes over the years. In the early years, when the total strength of the C.I.D. was five officers who were involved in general investigative duties as well as fingerprint examinations, to the present day when the Department is divided into specialized units….. Photography, Scenes of Crime Officers and Fingerprint Officers.

Valuable assistance is also provided by the Government Analyst, Dr. Alan Young, and Dr. Keith Cunningham at the King Edward VII Memorial Hospital. Fornesic examinations are carried out by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Laboratories and we are still able to call on the assistance of New Scotland Yard whenever the need arises.

________________________________________

1985 – 1986

(Photo courtesy of Keith Cassidy)

1987

1988

Stephen Perinchief leaving Do April 1988

Stephen Perinchief leaving Do April 1988

1990

1990

1996

1998

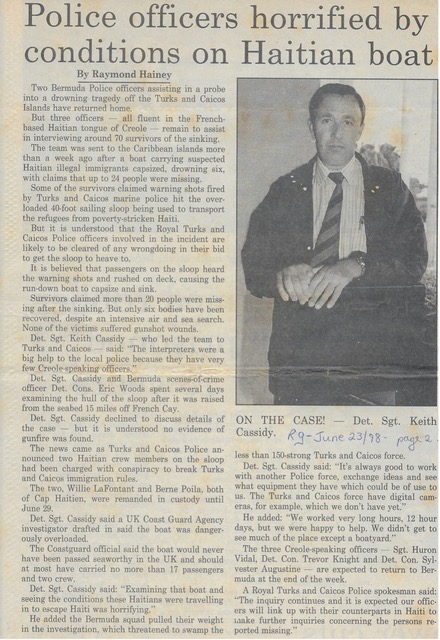

The (RG) reported locally on the matter a week later in the article below dated June 23, 1998.

A followup article in the (RG) dated Wednesday, July 1, 1998 revealed the following facts:

Mr. Kelly – a former Deputy Governor of Bermuda – wrote to Governor Thorold Masefield after the last three of the of the five-strong Island team sent to TCI returned home.

The TCI Governor said:

“On behalf of the TCI government and people, I wish to express our deepest thanks for the assistance provided from Bermuda.

“I would be grateful if you would pass on these thanks to the Commissioner of Police and the Premier of Bermuda.”

The five strong team – a mix of detectives and officers fluent in Creole or French – were drafted in after a boat carrying refugees from the Caribbean island of Haiti went down off TCI.

The ancient sloop – said to be packed with alleged illegal immigrants to Turks and Caicos – capsized last month. Six people are known to have died. Some survivors claimed warning shots fired by TCI police in a bid to get the boat to heave to hit a passenger.

But it is understood the sloop was raised and examined and investigators found no evidence of bullet damage. None of the dead suffered bullet wounds.

Acting Inspector Keith Cassidy, Sergeant Huron Vidal, and Pc’s Trevor Knight, Sylvestor Augustine, and Eric Woods travelled to TCI to help in the investigation.

Acting Det. Insp. Cassidy and Det. Con. Eric Woods, the investigative part of the team, returned home more than a week ago. But the three others remained to finish interviews with the 70 survivors of the wreck, whose native tongue is the French-based Creole.

He said three TCI police officers suspended after the incident – understood to be the crew of the police patrol boat – had been cleared and now been returned to duty.

But two crew members of the death-trap sloop have been charged in connection with the incident.

Mr. Kelly added the work of the Bermuda team was “of enormous benefit” to the investigation, which is almost complete.

Said Mr. Kelly:

“The Superintendent in charge of the investigation speaks most highly of the competence and effectiveness of all these men.

“They worked extemely hard and enabled the interviewing of the surviviors, none of whom spoke English, to be completed very quickly.

“They were a great team and worked well with the officers of the Royal Turks and Caicos Islands Police and others involved in the investigation.”

Evidence introduced by photographs, video and audio recordings, charts, etc. is considered to be ‘demonstrative’ evidence because it directly demonstrates a fact. When properly introduced it can be a common and reliable kind of evidence.

Sometimes, DNA evidence can link one offender to other crimes or crime scenes. This linking of crimes helps investigators to narrow the range of likely suspects and establish patterns of crimes towards identifying and prosecuting suspects.

The trial judge alone has the ultimate decision in determining whether or not a witness presented to the court by the prosecutor (or by the defence) is sufficiently qualified to be regarded as an expert witness. The judge must examine the witness as to his status as an expert and such examination must elicit the witnesses experience, skill, knowledge, education and training which will help the triers’ of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue.

Under the rules, an expert must disclose the facts or assumptions upon which his or her opinion is based and such facts and assumptions must be capable of proof by way of admissible evidence which must be admitted to prove the facts and assumptions upon which the opinion is based.

Generally speaking an expert witness is one who has devoted time and study to a special branch of learning and who is well-skilled in the areas upon which he is asked to state his opinion. Unlike a lay witness, an expert witness does not have to have firsthand knowledge of the case in order to form, or to testify to, an opinion. Instead, the expert witness's opinion may be based on the witness's application of reliable principles and methods concerning the facts or data in the case.

It is often necessary for a forensic technician, analyst or video forensic expert to perform a digital video evidence recovery in order to secure the Digital Media Evidence (DMA) and establish a chain of custody. DME can be defined as “Information of probative value stored in binary form”

He further said, “I have no idea what happened to all the old Hasselblad photographic cameras and lenses after we went digital in 1996. However, they were worth a fortune”.

A forensic handwriting expert may be known by various names; forensic document examiner, handwriting analyst, handwriting examiner, graphologist, or even a questioned document examiner.

The forensic handwriting expert is concerned about authorship and authenticity of documents. In other words, he/she is a professional trained to detect the authenticity of documents. This is done by examining the writings of individuals to discover useful information which is contained in the pattern of writing, and which reflects the state of mind of the writer.

Documents which can be examined by a handwriting expert can vary from wills to suicide notes or even to materials suspected to contain hidden marks intended to convey meanings.

[It was once the norm in Bermuda for large-volume drug hauls to be physically escorted under tight police security from storage in the Narcotics vault for display in the Supreme Court as evidence before a judge and jury. Such large volume evidence was later presented in still or moving images, or described in text, audio or video – or simply referred to in witness statements.]

The growing popularity and acceptance of police photography resulted from the prominent belief in the realism of the medium.

Photography is the basis of all crime scenes and is carried out on priority. Photographs and crime sketches are the most effective and simplest way to represent a crime scene by the Investigating officer. They are most useful in supplying significant bits and pieces with exact measurement of the site and evidence where the crime has occurred. The purpose of crime scene photography is to provide a true and accurate record of the crime scene and physical evidence present by recording the original scene and related areas. No matter how well an investigator can verbally describe a crime scene; photographs can tell the same story better and more easily as it freezes time and records the evidences. Forensic photography is an integral part of trial. And the judgement often is based upon crime scene photographs to prove prima facie evidence.

CLICK HERE For a review on the importance of still photography at a crime scene

CLICK HERE For an interesting insight into crime scene photography

CLICK HERE For an updated History of Fingerprints

For more related discussion see:

Jaeger, Jens. “Police and Forensic Photography” The Oxford Companion to the Photograph. Ed. Robin Lenman: Oxford University Press, 2005.