Francis John Farmer, ‘Frank’ to his many friends was born on 3rd February 1926 to Alfred H. and Maud Farmer. In 1939 they lived in the Borough of Malden and Coombe in Surrey, England. Frank was still at school and his father was an interior decorator. At the age of 17 Frank joined the Royal Navy, where he was to become a Stoker on HMS Ulster.

Frank Farmer's HMS Ulster crest

Frank Farmer's HMS Ulster crest

HMS Ulster, commissioned on 25th June 1943 was a U class destroyer which was later converted to a fast frigate for anti-submarine duties. Initially based at Scapa Flow for escort duties, in September 1943 she was transferred to the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel to intercept enemy convoys. On 3rd October during such a mission HMS Ulster received two shell hits.

In September she was moved to warmer climes and saw action in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic and was an escort to some of the vessels taking part in the Anzio landings in March 1943.

In May 1944 HMS Ulster returned to the Home Fleet where she took part in exercises which culminated with the ship providing naval gunfire support for the D-Day assault landings on GOLD beach. During these operations she ran aground and it was later found that the port propeller was missing and that the starboard one was damaged. On 22nd June HMS Ulster arrived in Cardiff, Wales for repair.

In October the ship commenced an extensive refit prior to being deployed to the Far East where she arrived in March 1945. HMS Ulster became part of a Task Force which included the Battleship King George V and the Aircraft Carriers HMS Indomitable and HMS Illustrious. The Task Force took part in operations in support of the U.S. forces Landings on Okinawa, Japan.

On 1st April HMS Ulster was damaged by a near miss from a 500 lb bomb jettisoned by a Japanese Zeke aircraft being pursued by a Seafire aircraft. This caused major damage to the Engine Room and the Aft Boiler Room. Two personnel were killed and one was seriously injured. The ship was disabled but her armament was still available. HMS Ulster was taken in tow to Leyte in the Philippines for temporary repair in the dry dock there. Subsequently she sailed to Chatham, England, arriving in August and she was then paid off.

I am indebted to the website ‘Norries Net’ for the above information on HMS Ulster’s wartime activities. The website is run by Mr Norrie Millen, a former HMS Ulster crewman, who was part of the crew when the ship was based in Bermuda in the 1960’s.

On 27 September 1947 Francis John Farmer was appointed British Constable No. 10397 in the Palestine Police Force. However the British Mandate ceased on 15th May 1948 and so Frank was soon back in England looking for another job. Apparently he liked travelling and for a while was a Prison Guard in Canada. That did not last long as he is recorded as returning to England on 22nd September 1950.

Frank's Palestine Police key ring

Frank's Palestine Police key ring

On 10th July 1952 the ‘Reina Del Pacifico’ departed Liverpool, England for the ‘west coast of South America’. On board were Raymond C. Barnewall of County Cork, E.J.E. Bailie of Belfast, Northern Ireland, Leslie Waddell of Belfast (who because of a typo was listed as a housewife!!!), and Francis John Farmer. All were listed as Police Constables bound for Bermuda.

Government Notice 313 - 1952 in the Official Gazette of 28th July 1952 stated that Frank’s appointment was from 7th April 1952. Constables Barnewell, Baillie and Waddell were appointed from 11th March 1952.

The Royal Gazette of 22nd July 1952 noted that the Constables were not the only new recruits to the Bermuda Police Force.

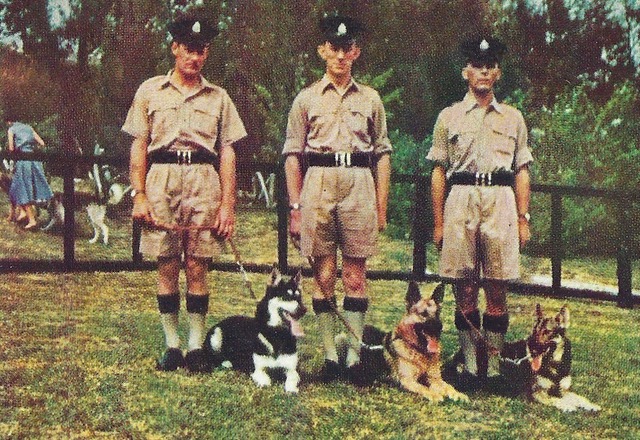

The dogs, the first to be acquired by the Bermuda Police Force, were accompanied to the Colony on the P.S.N.C. liner by their special police trainers. They will soon be put to work in the prevention of crime.

“Bruce,” a large fawn and black animal, is under the care of P.C. Raymond Barnewall, 21, of Cork, "Bruno," who obeys the commands of his trainer, P.C. Leslie Waddell, 23, of Belfast, Northern Ireland, is black and tan. P.C. Frank Farmer, 26, of Worcester Park, Surrey, England, is in charge of “Flash,” a lovely black canine, and P.C. Edward Bailie, 23, also of Belfast, takes care of “Prince,” a black and brindle dog.

Three of our first four police dogs at Annual Agricultural Show - 1954

Three of our first four police dogs at Annual Agricultural Show - 1954

The animals range in age from nine months to 13 months and weigh from 60 to 80 pounds each.

For the past four months they have been in the constant company of their trainers who took a special course with their charges at the Scotland Yard dog training division at Imber Court, Surrey. P.C. Farmer has done police work previously and was stationed in Palestine for 12 months in 1947 and 1948.

The trainers, who are also additions to the local force, explained that the dogs work on an average of six hours a day, six days a week. On the seventh day they are given an hour’s training. These men will be used exclusively for work with the police dogs.

When the animals are taken out on a job they may be on a leash or they may be let loose to “heel,” depending on the particular mission.

The dogs have been eating one and a half pounds of meat (horseflesh) and one pound of biscuits daily, according to their trainers.

Passage on the Reina for each dog cost the Bermuda Government £15.10s. The new constables in charge of the dogs would not disclose the methods used with working the dogs for fear of giving away secrets. Training the dogs, they added, requires a lot of patience.

Frank Farmer married fellow Londoner Pat Farr on 18th December 1954 as reported in the Royal Gazette of 29th December 1954:

Frank and Pat on their wedding day - 18th December 1954

Frank and Pat on their wedding day - 18th December 1954WEDDING Farmer - Farr

Mr. and Mrs. Francis John Farmer are at home at "Tobermory Cottage”, Paget, after their marriage on December 18 in St. Mark's Church, Smith's Parish. The bride is the former Miss Patricia Margaret Farr, a teacher at the Whitney Institute, and the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur William Farr of Pinner, Middlesex, England.

The bridegroom, who is with the Bermuda Police Force, is the son of Mr. and Mrs. A. Farmer of Worcester Park, Surrey, England. The Rev. Frank Ross officiated at the ceremony, held before an 'altar decorated with white gladioli' and Bermuda Easter lilies.

'The King of Love My Shepherd Is" and "Love Divine, All Loves Excelling" were sung during the ceremony. Mr. T. Brannon was the organist. Given in marriage by Mr. H. Ford, the bride wore a blue corded silk cocktail suit and carried a spray of white glamelias and tuberoses.

Miss Pamela Barrett attended the bride and wore a princess-style gown of blue corded silk and carried a spray of mauve passion flowers. Mr. William Kuhn, Jr., was the best man and Mr. Tommy Gray and Mr. Peter Jackson were the ushers. After the ceremony a reception was held at "Dean Hall", Flatts, the home of Mrs. Lillian Peniston.

They had two daughters, Penny and Sharon. Frank resigned from the Bermuda Police Force on 6th October 1955 and later joined Masters Ltd where he worked for 30 years. He also became heavily involved in veterans affairs in Bermuda and for years was the President of the War Veterans Association.

On 5th June 2004 the Royal Gazette published a story by their reporter Danny Sinopoll to mark the 60th anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy.

A Royal Gazette photo published with this article with the caption:

It was one of the greatest military operations ever staged and marked the final turning of the tide against Hitler’s Germany in the Second World War. But the cost of D Day, which took place 60 years ago tomorrow, was also enormous. The following story was published by The Royal Gazette on the 50th anniversary of the Normandy Landings in 1994. We reprint it today to mark the 60th anniversary. Mr. Martin Smith has since passed away.

It was on the rainy night of June 5, 1944 mere hours before one of the biggest military campaigns of the modern era that Frank Farmer, then a fresh-faced Londoner of 17, first became aware a crucial turning point in the Allies long struggle to force an end to the Second World War was at last on the horizon.

'They kept us in the dark until the night before, says the 68-year-old Paget man of the news that he and his shipmates on HMS Ulster, a Royal Navy destroyer off the coast of Ireland, would have a part in the massive amphibious landing Operation Overlord.

As young boys, we were very excited about (that landing), which began, a little before dawn, 50 years ago today.

At the same time, Ronald Firth, a Yorkshire-born petty officer who had just turned 21 in May, was on a Landing Ship Tank, LST Number 11, at the English port of Southampton.

'We were loading the Canadians who would land at Juno, he said recently from his home in Smiths Parish. Juno was the code name for one of the five rocky strips of shoreline that would serve as entry points for the following day’s assault on Nazi-held France.

Unlike his two brothers in arms; Martin Smith, one of the few native-born Bermudians to have played a direct role in the assault, said he knew of the invasion as early as June 3.

An RAF flyer at the time, he was returning from a 48-hour leave period to his base near Down Ampney, a sleepy English village in Wiltshire, when he noticed a massive congregation of aircraft by a roadside.

As I turned off the road into Down Ampney, I realised then that the invasion of northwest Europe was about to take place, he told.

Five decades and an ocean now separate these men from that horrible Wednesday in 1944. Mr. Smith returned home to become a successful businessman, Mr. Farmer and Mr. Firth to begin new lives and long residencies. But even the passage of 50 years, which anniversary celebrations in several countries will mark this week, cannot dim their memories of both the glory and the butchery of that all-important assault on Fortress Europe.

Hampered by winds and tides, the 50th Division suffered high losses in soldiers and tanks, Mr. Farmer, a stoker in the Ulster’s engine room, recalls.

Thousands would die during the invasion; more than 2,000 Americans on Utah Beach alone.

Utah, another code name, was the westernmost point on a 60-mile stretch of coast between Caen and Cherbourg that had been divided among the Allied Forces when they planned the assault. In that process, Utah and Omaha Beaches had gone to the Americans, Gold and Sword to the British and Juno to the Canadians.

The Germans, commanded in Normandy by the Desert Fox of North Africa, Erwin Rommel, had been expecting an invasion the Allies had been planning one since 1942 but both Hitler and Rommel thought it would come at Calais on the Channels narrowest point.

To encourage that belief, the Allies set up a phantom First Army under General George Patton just across from Calais in Kent.

The ruse ultimately worked, although the Germans probably should have realised that Calais, with its high cliffs, would have been all wrong for an invasion.

Normandy was chosen by the Allies because it had mostly sloping beaches and was near the port of Cherbourg.

Choosing Normandy also meant the invasion would be highly dependent on a low tide and the weather. D-Day was supposed to have been June 5, but a storm put an end to that plan.

When the weather analysts subsequently predicted a brief clearing on the sixth, the Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, gave the go-ahead.

The days, indeed the months, prior to that order were ones of fevered activity for Mr. Smith, who had been studying in England when the war started and was obliged, as a British subject, to offer himself in defence of the realm.

As we approached June, our training intensified and we developed a very close relationship with the parachuters, he said.

Mr. Firth, meanwhile, had been in the Mediterranean, where the LST on which he was stationed had assisted in the Italian and North African campaigns. Known as the ugly ducklings of the Navy because of their cumbersome appearance, LSTs were 300-foot flat-bottomed boxes that were capable of carrying 20 tanks and 27 trucks to an invasion beach and then hauling themselves off to return for another load.

They proved vital to the Normandy invasion.

When the invasion finally came, at 5.30 a.m. on June 6, the massive Allied assault fleet was firmly in place. Surprisingly, none of the veterans recall experiencing any fear at this time. Instead, they remember a sense of '.excitement and a preoccupation with getting the job done.

In Mr. Farmer’s case, the mood was one of prevailing calm.

Once the Ulster’s guns started to fire, you felt almost safe in your mind, he says. Deep in the bowels of the destroyer, there was no sense of how the invasion was going until much later in the day, when the first landing crafts started to come back, Mr. Farmer recalls.

For the next few days, the Ulster pounded Gold Beach with artillery, allowing the British to make the crucial but painfully slow move inland.

On the third or fourth day, Mr. Farmer says, the Ulster ran aground and was effectively out of commission. It was eventually towed to Portsmouth, where Mr. Farmer sat out the rest of the invasion. That was the end of D-Day for me, he says. The end, as it were, had come slightly earlier for two of Mr. Farmer’s schoolmates; one died on the second day of the invasion and another lost a leg.

Echoing Mr. Farmer’s sentiments, Mr. Firth says he too had experienced little fear, although he admitted to a claustrophobic sensation in the tomblike innards of the LST.

He also says he wasn’t fully conscious of the danger until much later in life. I saw one or two LSTs go. But I didn’t realise how many had been sunk.

Of the three veterans, Mr. Firth got the closest to the enemy. Having assisted in the attack on Juno Beach, his was among the first groups of LSTs to return to England with German prisoners of war.

I felt sorry for them, he says of the captives who were in many cases younger than him. Herded into the bottom of the craft, 'they were covered from head to foot in mud, they were seasick and there were no toilets’.

Once the re-conquest of Europe was well under way, Mr. Firth sailed for campaigns in India and Burma and was at Singapore for the signing of the Japanese surrender. After briefly considering South Africa, he came to Bermuda in 1949. For Mr. Smith, who received his flight training on the Canadian Prairies and spent some time ferrying B-26 bombers across the South Atlantic, most of D-Day was experienced from above.

As the youngest pilot in the 48th Squadron one of the main objectives of which was to knock out a German gun emplacement at Merville, near Sword Beach, he was one of the last fliers of his group to go over Normandy.

Considering what ultimately happened, he could also have been one of the few that didn't comeback. The trouble started on the second day of the invasion, after Mr. Smith’s Dakota, carrying the only all-Irish detachment of Royal Ulster Fusiliers, had emptied its men and released the glider that had gone up with it.

At that point, Mr. Smith says: l realised my plane had been hit because the starboard engine had gone out. One of the (German) bullets had apparently hit the fuselage and gone out ahead of my feet.

As if to confirm Mr. Smith's analysis of the situation, a cabin mate ran into the cockpit and shouted: Some bastard is shooting at us! By that point the Dakota had fallen nearly 300 feet and had to descend even further to avoid oncoming British aircraft.

At the precarious altitude of 100 feet, he carne through a thick haze to within firing range of the Allied vessels then bombarding Sword Beach and narrowly missed being hit by the British ship Warspite.

Thinking, 'l am not going to be shot out of the sky by the Royal Navy’, Mr. Smith managed to regain his bearings and hobble into an RAF base near Christchurch on one engine.

Upon landing, a fellow flier turned to the relieved young pilot and heartily wished him a Happy 21st Birthday, Mr. Smith recalls, his eyes tearing up at the memory. After that initial sortie, Mr. Smith returned to France to help with the evacuation of the wounded. I will never forget that first trip, Mr. Smith says, remembering a man with a particularly severe stomach wound. Gangrene had set in, and you could smell it.

Another soldier, a great big corporal from Middlesex Regiment, had been shot in the face, leaving a big, gaping hole.

Recalls Mr. Smith: You could see half his tongue. His teeth were shattered. He couldn’t speak but he was conscious.

Needless to say, there are mixed feelings at such recollections, especially during this very important anniversary. On the one hand, there is a disgust at the kind of violence that had such an impact on their young lives and which has once again reared its head on the European continent.

Will (the remembrance of D-Day) achieve world peace Mr. Farmer asks. We hope it will.

On the other hand, there also exists a demonstrable though quiet pride at the accomplishments, collective and individual, of that very special effort the like of which, given the time and resources, will probably never be repeated. Says Mr. Smith: The fact is we won, and the world was changed

It certainly did. Almost three months after the Normandy landing, the Allies were in Paris, and shortly thereafter had liberated France. Now facing two fronts, a weakened Germany was overpowered by the following May, allowing the victors to turn their attention to the war in the Pacific. Of course, the Allies paid a terrible price for that privilege in terms of loss of life.

But though that price was high, no one would dispute that an Allied loss on D-Day would have resulted in a blow to democracy from which the Free World might never have recovered.

As Mr. Smith says: The alternative would have been incomprehensible.

Francis John ‘Frank’ Farmer died on 29th June 2014 in Bermuda. The Royal Gazette carried an obituary on 3rd July 2014.

D-Day veteran Francis (Frank) Farmer, a former president of the Bermuda War Veterans Association, has died at the age of 88.

Mr Farmer joined the Royal Navy at 17, signing on in 1943 and serving around the globe in the Second World War. He took part in 1944 Allied assault on Nazi-occupied Europe, as a stoker aboard the HMS Ulster— a destroyer that provided covering bombardment for the British and Canadian soldiers swarming ashore at Gold Beach, Normandy.

The vessel also served in the Allied campaign in the Pacific. Stationed in the engine room, Mr Farmer was vulnerable to torpedoes, telling The Royal Gazette in 2004: “We had other things to occupy our minds — you tried not to think about it."

Two of his brothers were not so fortunate: Philip, 18, was killed in 1940 while serving in the British army in France, and Harry, 21, of the Royal Air Force's Bomber Command, died over the North Sea the month before.

Originally from South London, Mr Farmer was so young that he needed his father's permission to sign up widow Pat Farmer recalled. During the Pacific campaign with the Ulster, she said “the ship was bombed by a Japanese kamikaze — Frank was in the engine room and able to escape, but three of his mates were killed. “ He was still in the Pacific when Japan surrendered."

Demobbed in 1947, Mr Farmer served in the UK‘s Palestinian Police during the post-war tumult between British peacekeepers, Jewish refugees determined to settle in Israel, and Palestinians.

He later moved to the prison service in Canada before coming to Bermuda in 1952 as a police dog handler.

A year later, he met the fellow Londoner who, in 1954, became his wife. “Frank was a very gentle person — we had two daughters, Penny and Sharon, and if they needed discipline as children he would never lay a finger on them," Mrs Farmer recalled. “We had a very happy marriage. We were very busy, working all our years. Then, when we retired, we seemed to get even closer."

Mr Farmer worked in various businesses before settling at Masters for about 30 years, but was best known for his dedication to veterans. He served on the board of the Mariners Club and was a long-standing president of the War Veterans Association.

Successor Jack Lightbourn described his former colleague as “a good fellow — I got along very well with him. He didn‘t talk much about his war experience, and even though I spent a lot of time with him, we never did discuss an awful amount of what we did.”

“He was active and saw quite a bit of the world. Of course he was very active with the veterans, and when they had their club, that was how he got his first real start."

Mr Farmer, who died on Sunday, will be laid to rest at St John's Church in Pembroke this Saturday at 10 am.

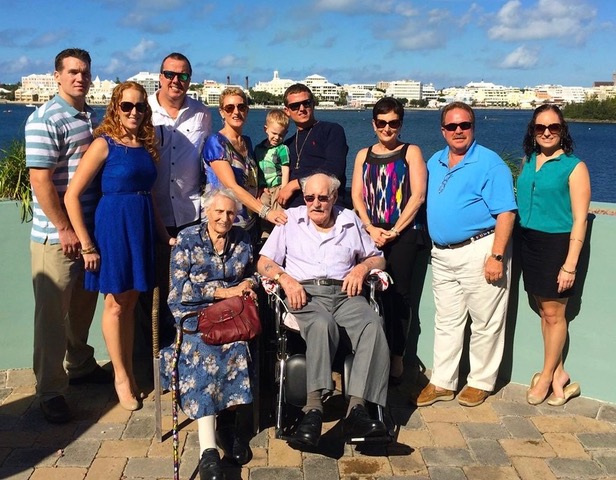

The Royal Gazette of 8th February 2022 carried the following Notice which said in part:

A service celebrating the life of Patricia (Pat) Farmer, beloved wife of the late Francis (Frank) Farmer, loving mother to Penny (Andrew) White and Sharon (Keith) Penn, grandmother to Nicola MacDougall (Brian), Christina Cribbin (Daniel) and Aaron Fenn (Allison Parry, Fiancée), great grandson, Brandon MacDougall, and special caregiver Bernadette (Bernie) Landingin, will be held on Wednesday February 9th, 2022 at St John's Church, Pembroke at 4pm.

In lieu of flowers donations in her memory maybe made to St John‘s Church for the purchase of cushions for the Church Pews.,

Please put "Pat Farmer cushions" as a reference.

In accordance with Covid 19 restrictions attendees are required to wear Masks and adhere to social distancing guidelines. Bulley-Graham-Rawlins Funeral Home and Cremation Services.

EDITORS NOTE - Upon hearing about this article being published on our ExPo website, the Farmer Family kindly provided us with several of the photos accompanying the article, including the photos of our first ever police dogs, Frank and Pat's wedding photo, Frank at the 11th November Parade with all his medals, and this photo of Frank and Pat srrounded by all the members of their Bermuda family.