Reminiscences of David Mulhall

Like a recent British movie, I too was "Made in Dagenham," that quintessential working class British town with its drab council house "estates", fish and chips shops, and dense, sometimes, lethal smog.

My dad worked on the assembly-line at the Ford factory, and after picking up a few "O" Levels at the local Secondary Modern, I joined Ford as a Parts List Clerk. As an escape from the job's boredom, I joined the Kensington-based counter-espionage branch of the RAFVR police. My employer had no choice but to hold my job while I flew off to practice catching and interrogating spies and terrorists.

Alas, with the end of empire, my unit disappeared. Sensing that my days at Fords were numbered, I resigned to take a temporary job as an assistant house-master (non-teaching) at a boarding school for kids from troubled families. The boys called me "Mr. Mudball" because I ran with the cross-country running team I coached. I had come to enjoy reading "quality" newspapers like the Observer, but their employment opportunities sections had little to offer to people like me. Normally, I made a point of not reading the notorious "popular" press, but one day while trapped at my mother's house by dense smog, I glanced at her gossipy Daily Express. There I spotted an advertisement for the Bermuda Police - no experience or special qualifications needed.

The hiring process comprised a brief, painless interview and a medical. Within a few weeks I had my plane tickets. It was May 1964, and I was 21 years old.

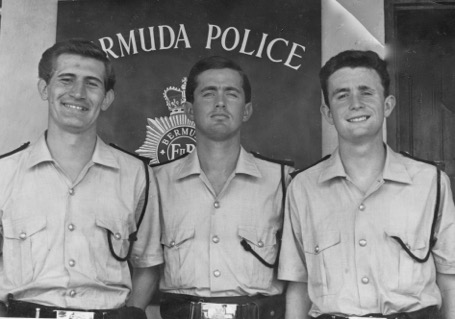

I had already resolved to change, beginning with a new wardrobe. So the next morning I donned my new made-to-measure Saville Row tropical suit, slipped into expensive brown suede shoes, combed my longish hair, and "disabled" my already attenuated working class Essex/London accent. Although this elegant "fashion statement" left me penniless, what happened when I arrived in Bermuda convinced me that my image remake was working - perhaps too well. I went to board the police van along with the other eleven recruits, but the police driver told me I was in the wrong line: this one was only for police.

I got used to the teasing that my sartorial idiosyncrasy tended to invite. But I never did get used to Bermuda's racial divide and its attendant injustice and resentment. The civil servants who interviewed prospective recruits in London quite properly asked each if he would object to having non-white superiors, thereby giving the generally accurate impression that the Police Force was an integrated meritocracy. But they failed to mention that the colony's schools, Bermuda Regiment, yacht clubs, the Boy Scouts, and some hotel swimming pools were still racially segregated. Hence my feeling of having been misled when I first encountered the legalized racial discrimination known in those days as the Color Bar.

I had been invited to join a police swimming team hastily put together for a competition with a team from a visiting British warship. The evening meet was held at the St. George's Hotel, but it was not until the following morning that I learned from one of the two "coloured" Bermudians in our training school class that his brother, a highly respected Constable and member of the police team, had been barred from using the pool because of his race. That our team captain knew of this but failed to inform us made me feel like an unwitting accomplice.

Our muted response embarrassed and annoyed me. It also stimulated an intellectual and political curiosity concerning race and racism, conquest and colonization. I learned, for example, how Bermuda's white minority controlled government had operated through an ingenious system of plural voting which not only limited the right to vote to property owners but granted them a vote for each piece of land owned in any given parish. The white descendants of former slave owners, who of course owned most of the land, were thereby able to control the government without resort to explicitly racist laws.

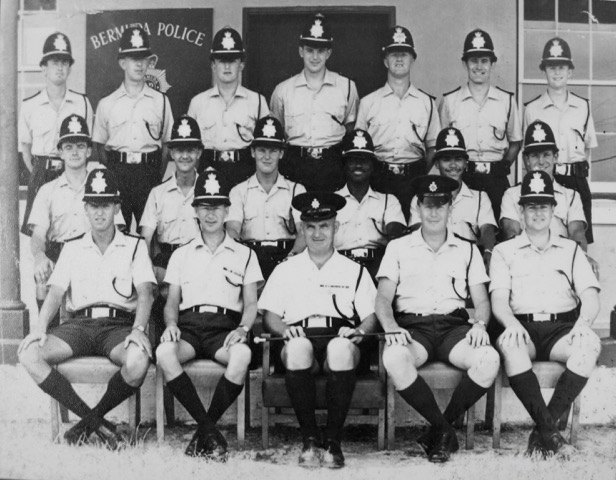

As I acquired sensitivity to racist attitudes and behaviour, I came to appreciate their absence in my Training School classmates, who included Dave (The Admiral) Long, Ray Banks, Wayne Perinchief, Peter Duffy, and the late Willie Galloway. I enjoyed the eclectic, low-key training - in First Aid, unarmed combat, ocean life-saving, "square bashing", law, criminal investigation, but, unwisely, not riot control.

On completion of the basic training I was awarded the Bermuda cedar "Baton of Honour" for being the "Best Recruit." I felt pleased with myself for resisting the temptation to "party" my life away. The cheap booze, air-conditioned mess bar, and an apparently inexhaustible supply of unattached female tourists made it an attractive option, though not as attractive as the pretty, petite Canadian nurse I met at a “hurricane party”!

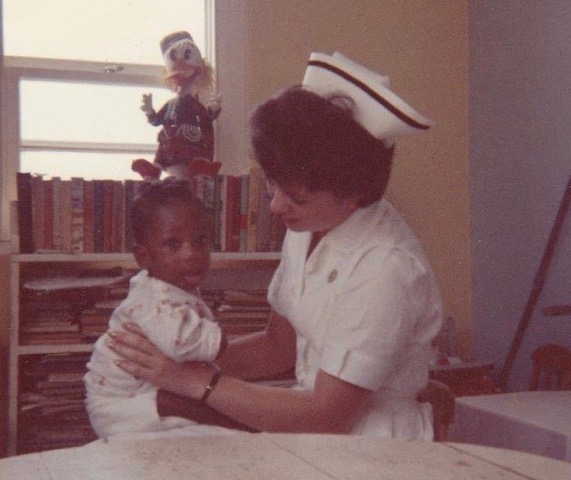

With most of Bermuda's nurses and police officers being young, single ex-patriots who lived in residences, fraternization was not only inevitable, in my experience it was encouraged and even arranged: the Training School life-saving instructor, John Rawson and his fiancé, the children's ward Head Nurse, conspired to have me escort a newly arrived Canadian RN to a nurses' dance.

The "blind date," an alien concept for me, appeared to entail an unacceptable level of risk. So I refused to give an answer until after I had secretly arranged to catch a glimpse of her at the Admiralty House Cove, a beach reserved for police officers and nurses. She passed the test, but a hurricane warning meant that the dance had to be postponed, since both nurses and policemen had to be available to handle any emergency.

But why not have an impromptu hurricane party in a big cave at Prospect, the barracks, admin and mess complex? The Nurses Residence was not far away, and so in no time at all a couple of police mini-buses were dispatched to pick up nurses. I went with one van, introduced myself to Frances Warner, my date, and escorted her to Prospect.

We enjoyed the party, especially the dancing, and before long there were frequent sightings of a young lady riding side-saddle on the pillion of my BSA motor cycle. Although I did not realize it at the time, she was to have a moderating influence on me. I began to take life more seriously just after she arrived. She also discreetly set about smoothing some of my rough edges. I recall, for example, one occasion when, on leaving a party, she said that she would enjoy my company more if I was less critical of people. This discretion, together with her reserved manner and modesty, convinced me she must be a good nurse.

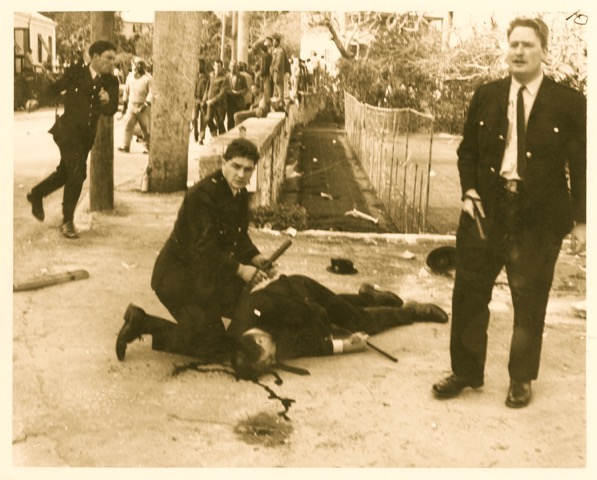

I did not expect to ever see her in action, since she worked on the Children’s Ward, and I never ventured beyond the Emergency Department, but on the morning of February 2nd 1965, she was sent down to help the Emergency staff cope with 17 policemen injured in a clash with a large, angry mob of striking workers at the Bermuda Electric Light Company (BELCO) plant on Serpentine Road. I lay on a table with my head facing the door having a cut on my chin sutured when she walked in, spotted me and without a word or gesture promptly went to tend to Constable Ian Davies, who had sustained head injuries severe enough to end his career.

At the time I thought I had been lucky to have sustained just multiple cuts and bruises. I now know that the Parkinson's disease which ended my academic career prematurely may well be linked to the blows to my face and head, courtesy of the Bermuda Industrial Union.

Given Bermudians' strong, almost morbid preoccupation with race and the close correlation of race with social and class status, labour/management conflicts invariably became racial in nature. Interestingly, according to police intelligence reports, the "racialization" of the BELCO strike seems to have occurred despite the union leaders' efforts to "contain" it .The BIU's members were overwhelmingly hourly-paid blacks; BELCO's owners and most of the salaried staff were white.

Any negotiations between the two parties would inevitably be soured, on the BIU side of the table by the persistence of such blatantly racist practices as the segregation of washrooms. On the other side, the BIU's energetic and successful leadership of Bermuda's trade union and Civil Rights' movements was bound to upset and frighten the white colonial elite which essentially “owned” not only the big companies like BELCO but, despite being a minority, the government itself. The prospect of one day having to defend the interests of these powerful elite made me feel uncomfortable. I admired Dr. Martin Luther King and openly sympathized with the BIU’s commitment to Bermuda’s political and social decolonization.

One of the most important of those elite interests was the Bermuda Electric Light Company. By late 1964, a substantial number of its hourly-paid employees, mostly linemen, had joined the BIU, which then approached the company to request recognition and bargaining rights. BELCO agreed to negotiate, and after a number of meetings with the BIU's leaders, offered to recognize the union if at least 51%of BELCO's hourly-paid workers voted in favour of joining it.

Fearing that it would not win at the ballot box, and seriously over-estimating its ability to disrupt the company's operations, on January 14, 1965, the Union called its members out on strike.

Despite the use of aggressive and clearly illegal picketing, as well as some dynamiting of company installations, the Company remained adamant in its refusal to accept the BIU's original demands. The Union was used to winning unionization campaigns, and its leaders reacted to the humiliating prospect of failure by an escalation of tactics and the appearance of a greatly intensified rhetoric of abuse and violent threats. The police bore the brunt of this openly racist vitriol.

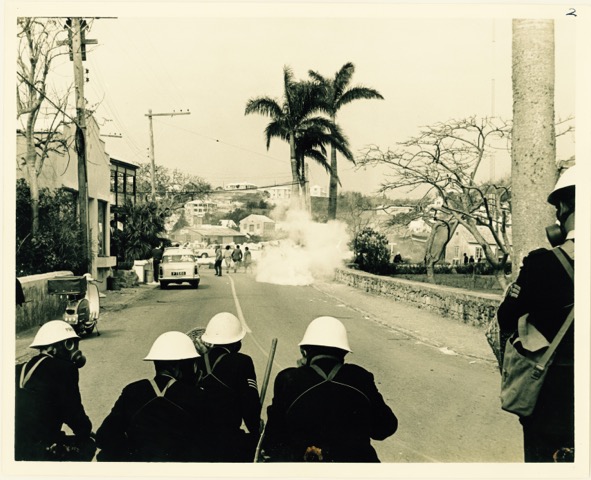

On February 1, police intelligence officers predicted that violence would break out the following morning. For not only had the mood of the BELCO strikers become more openly belligerent, but that evening the BIU called on all its members in other industries to join it in a general, sympathy strike, and to demonstrate their solidarity by joining the BELCO picket line the next morning. So many did so that by mid-morning picketers outnumbered the police by an estimated 6 or 7 to 1.

Some 45 years later BIU president Simmons told a young and deferential journalist that it was at this point that "metal pipe wielding" police "attacked" the striking pickets, who had of course to defend themselves. The metal pipes are a figment of Mr. Simmons' imagination. The police "attack" occurred after a group of non-unionized workers asked the police to open the picket line so that they could exercise their legal right to go to work. When three policemen approached the picket line, they were set upon and severely beaten by a group of about 60 men, many of them armed with weapons from a central cache.

This deliberate, obviously planned and potentially lethal resort to armed aggression against the unarmed and vastly outnumbered police is probably best understood as a result of turning the solid, unbroken picket line into a symbol of union and, perhaps, racial solidarity. It would follow that any attempt to "break" it would be felt as a humiliating provocation that warranted a violent, punitive reaction.

As more weapons were passed along the picket lines, assaults on police officers, usually those traveling in small groups, became more frequent. Still the riot control units held on reserve at Prospect and the Hamilton Police Station were not called in. Instead, seven unarmed and unprotected men were sent in a police van to seize the weapons and to arrest those who were distributing them.

Predictably, these men were attacked and badly beaten. From about a hundred yards away I saw Ian Davies, one of the seven, being beaten by several men as he lay unconscious and bleeding profusely from a head wound. I ran to help, though I do not know how. Then, as I approached one of the assailants from behind, he raised a golf club above and behind his head. Acting before thinking, I wrenched the putting iron from his hands before he could bring it down on Ian again. I then experienced an intense wave of irrational self-satisfaction and relief as I threw it over a nearby wall. Perhaps foolishly, it never occurred to me to use it or the toy-like police issue baton to defend myself against the four or five assailants I had not disarmed.

Angered at having their beating of an unconscious man interrupted, they left Ian and turned on me with their motley array of improvised weapons: iron reinforcing rods, lengths of 2 by 4 wood, baseball bats, and my tiny baton which one of them had yanked out of its concealed pocket.

I think I very briefly lost consciousness when I hit the roadway "chin first." At that point, surrendering to instinct, I curled up in a ball and wrapped my arms and hands around my head. Fortunately, the timely arrival of police reinforcements scared off my attackers.

Because I had taken some advanced first aid/medic courses in the U.K., I attended to Ian while Constable George Linnen put himself between Ian and the rioters who were hurling rocks and bottles from across the street. A quick look at Ian's injuries convinced me that his skull was fractured and that he was losing a good deal of blood from scalp lacerations. Putting into practice what I had learned from a simulated "scenario" involving very similar injuries, I shouted for officers to give me their standard winter uniform ties, which I made into a donut-shaped compress to apply light pressure to his haemorrhaging scalp. There was nothing I could do to treat his fractured skull.

An ambulance sent for the police casualties was blocked for some time by the mob. Shortly afterwards, but too late help the injured seventeen, the riot units quickly, and with minimal discomfort for the rioters, cleared the street. The BELCO Riot was over.

The only extant written description of the police role in this "Disturbance" is a report prepared at the behest of Commissioner George Robins by Inspector J. C. P. Hanlon, a sort of in-house P.R. man. A copy of the report was sent to the Colonial Secretary in London. Clearly intended to divert attention away from the apportioning of blame, it does so by ignoring the whole question of personal responsibility and avoiding any critical analysis. Things just happened.

The reader is told, for example, that small groups of policemen, unarmed, untrained, and unprotected by proper riot clothing and gear, were ordered to disarm an enraged mob of about 300, but there is no mention of who gave that absurd order - and why. Similarly, the failure to provide any kind of crowd or riot control training at the Training School is simply not raised. Nor is the decision to deploy the two riot control units only after 17 men were injured.

No wonder Commissioner Robins thanked Hanlon "very much for this excellent report...." For the first two weeks of the strike Commissioner Robins' pursued a policy of appeasement - what might be called "reckless restraint." Designed, presumably, to avoid confrontations which might get out of hand, and thereby tarnish Bermuda's image, it had the opposite effect, as, for example, when illegal picketing became more aggressive once it became obvious that the law would not be enforced. Hanlon does concede that "to a certain extent" the decision to ignore this flouting of the law did contribute to further lawlessness.

By mid-morning on February 2, aware that his men had lost control, Robins apparently abandoned appeasement in favour of vigorous and prompt restoration of the rule of law. This meant breaking the picket line and disarming the rioters using the manpower and little truncheons originally mustered to implement the appeasement policy. Why Robins did not order a tactical disengagement until the riot control units arrived remains a mystery.

Beach Squad

You can't beat the beach for a beat. After the Belco debacle, I resumed the normal pattern of my job on the beat in Hamilton and my spare time with Frances on the beach - until going to the beach became my job! I was assigned to the Beach Squad, a four man unit formed after the rape and murder of a young woman on a secluded beach. Many years later I used to tell the students in a police history course that I had been lucky enough to have had the best two jobs in the world - teaching them and being on the Bermuda Police Beach Squad.

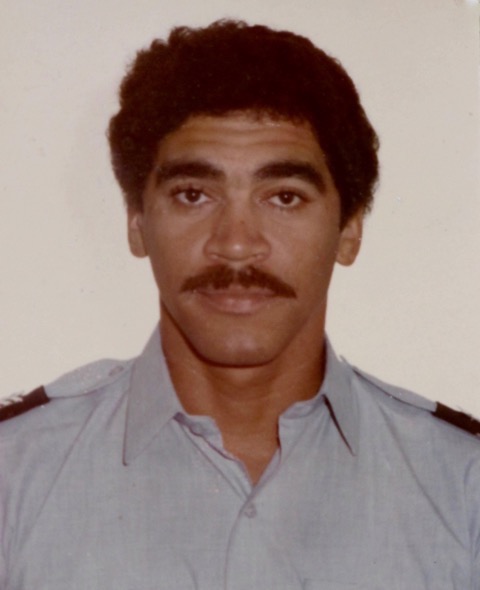

Wayne Perinchief

Wayne Perinchief

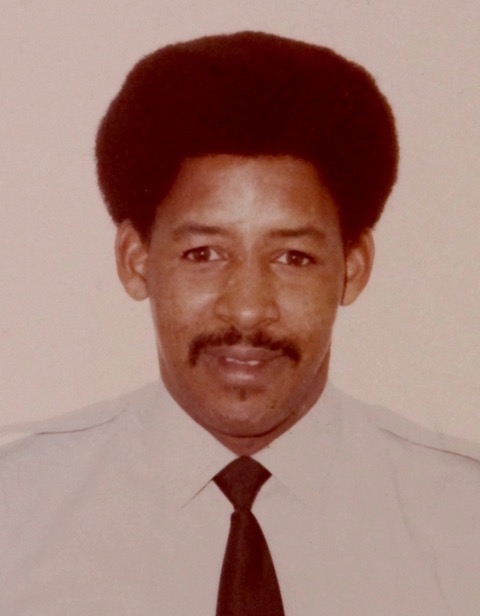

I had the good fortune of working with two "locals," Wayne Perinchief and Lawrence “Mincy” Rawlins. Wayne, who went on to become the Minister of Justice, encouraged my interest in Bermuda social and political problems. Lawrence, the most experienced member of the squad, became my informal mentor, though much of what I learned from him could not be found in any police training manual!

Long before GPS, he could locate the best parties. He also gave me a useful lesson on being "cool" when dealing with potentially difficult arrests. Acting on a tip from a trusted informant, we got warrants for the arrest of the members of a small gang of beach thieves. After tracking them to one of their favourite bars, I was gung-ho for going into the bar to arrest them. But as I approached the door, Laurence gripped my arm and guided me back to our van. He, recognizing the cars of friends of the suspects, did not wish to risk provoking a confrontation. We picked them up at their homes that night.

My most bizarre arrest as a police officer occurred on my final shift "undercover" in my swimming shorts, T-shirt, and flip flops. With my departure imminent, the last thing I wanted was a troublesome arrest. But I could not walk away when a horse covered with foam suddenly appeared on the always crowded Elbow Beach. The horse, clearly exhausted, and covered with foam, began to falter as it sought some relief in the shade of the same tree as me. The rider beat and kicked the poor beast, all the time screaming what were probably profanities in Portuguese. His slurred speech and unsteady movements strongly convinced me that he was drunk. So I informed him that he was under arrest for cruelty to an animal, and being drunk in charge of a horse. When he suggested that I should “f--k myself”, I added “using obscene language in a public place” to the charge sheet.

Police officers expect to have to deal with the kind of sordid behaviour exhibited by this drunken horseman. They do not expect to ever be seconded, however briefly, to the realm of the sublime.

My encounter began with a cryptic, hand-delivered message. Under the rubric confidential, it ordered me to report at 9am the next morning to Police H.Q. at Prospect, in my "Sunday Best," which for me meant my Saville Row suit and expensive brown suede shoes. What a change from my usual Beach Squad "plain clothes" attire! As soon as I got to Prospect I was told to wait in a sort of briefing room, where I would receive my instructions.

The late Pete Rose, then a junior DC, had arrived shortly before me. He had been told only that I would be his partner in a one-day secondment, and he was as impatient as me to learn the details of the mission. We both indulged in fruitless guess work: neither of us came up with anything as unlikely as having two young policemen spend the day escorting two beautiful models who had been flown down from New York to make a T.V. commercial for Nestles Iced Tea.

But at our short briefing it was made quite clear that our principal duty would not be protection but acting: we had to assume the male roles in the filmed commercial, which by the way I never saw. Perhaps that was just as well, for I realized that day that I was not a born actor: I felt self-conscious and silly sipping iced tea while at the helm of a luxury yacht sailing across Hamilton Harbour.

Still, the money was good, and the "work" not tiring, time-consuming or dirty - perfect part-time employment for a would-be university student, especially one who had a real Saville Row suit but little money. The Bermuda Tourist Board, which had been involved in negotiating the Nestle deal with the Police, kindly provided me with a two-picture portfolio which, in a few years, would open the doors of some Montreal modeling agencies at a time when I had difficulty financing my university education. I never did find out who had selected Pete and me for this sublime secondment!

If I had to identify one former Bermuda Police colleague as the most interesting, larger than life "character" I got to know "on the job" I would have no difficulty choosing Brian Malpas. - Until I realized that I had never actually worked with him. Brian’s escapades on or off duty were legendary and often hilariously funny, especially if he told the story. He loved recounting the details of his sometimes outrageous practical jokes.

I got to know Brian when I asked him if he would teach me to scuba dive and then allow me to help with salvaging of "treasure" from the wreck of a Spanish galleon. He told me that I should get a book and teach myself. When I could free dive (snorkel) to about 30 feet, he would let me use a tank. I duly "qualified" myself, and always using equipment borrowed from Brian, began a long and fruitful diving "career," which later included a stint working for Jacques Cousteau at Montreal's "Expo 67." I trained and directed a troop of young divers who put on an underwater exhibition of past and present diving devices.

The generous pay helped make it possible for me to devote more time to my university studies. So thanks Brian for giving me that rewarding experience, and for your generous hospitality when we returned to Bermuda as your guests in Somerset. After a day's diving Brian would be sure to catch our supper before we reached shore. While he prepared an exquisite dinner and downed enough beer to incapacitate most people, he would, if you were lucky, relate one of his stories.

Yet Brian had his serious side too. Before obtaining salvage rights on the 16th century wreck of a Spanish galleon, he was one of Bermuda’s top sailboat racers. He eventually collaborated with marine archaeologists from U.S. universities to identify and recover a large assortment of artefacts from the Spanish galleon. He donated this collection to the Bermuda Maritime Museum for display in a wing specially built for that purpose.

New Life and New Wife in Canada

I resigned from the Bermuda Police Force in September 1965 primarily to “follow” Frances to Canada, where I planned to go to Montreal’s McGill University. Frequently referred to as Canada’s Oxford, it was the Alma Marta of many of Bermuda’s professionals. Although I read widely and had a strong personal and academic interest in the kind of racial and colonial conflicts I had encountered in Bermuda, I found McGill`s doors closed to me. For I had failed high-school mathematics and had not taken Latin, which my Dagenham Secondary School did not offer. So I was unemployed and staying at the YMCA until I found a cheap room to rent.

Frances had planned for some time to do a six-month stint at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children, Canada's top children's hospital. On its completion, she would join me in Montreal. Meanwhile, I was faced with the inconvenience and expense of a long-distance courtship on top of my McGill rejection.

The prospect of living in a rooming house while looking for a job in a city where I did not know a soul, gave me a new appreciation of the life of a Bermuda Beach Squad "Bobby." I missed having friends to talk to, beaches to run along at dawn, and Mrs. Brangman at the police mess to cook the fish I brought back from diving with Brian Malpas. Had it not been for my strong feelings for Frances, I almost certainly would have tried to get back into the Bermuda Police.

Then, close to self-pity, I was rescued by an amazing piece of good luck. Walking to and from my YMCA Montreal room one evening I noticed a group of mostly young people lining up as though they were waiting to pay or register for something. I asked one of them what was going on. She told me they were signing up for evening classes at Sir George Williams' University, which I was soon to learn was named after the founder of the YMCA.

Designed to give a second chance to people like me, who lacked the qualifications and usually the means to go to places like McGill, it offered all its degree programs in the evenings. Within 24 hours I was accepted as a "mature student" in the B.A. program. All I needed now was a job. Police work was out of the question since I did not speak French at that time. I did, however, cut quite a dash in my Saville Row suite. Hence my decision to look for work in the service or sales sector.

My first job was with Drake Personnel, "placing" young women, mostly as secretaries. It was really high-pressure sales. All hard-to-pronounce or "Jewish" names had to be changed. I became Mr. Hall. Our conversations with clients were taped, and if you did not meet your placement quota you were fired. Of the group of six "counsellors” (all but me university graduates) hired in September 1965, I was the only one still with the company when I resigned six months later to become a trainee insurance underwriter.

So for my first two years in university I worked full-time while at the same time "carrying" a full course load at "Sir George." My determination to do well academically verged on the fanatical, and without Frances I could never have kept up the exhausting pace. Those years at Sir George were, in a way, harder on Frances than on me.

I weighed just 121 lbs. when we married on Boxing Day, 1966. I had lived on a diet of breakfast cereal and milkshakes in order to save time for studying. Frances prepared real meals that were both wholesome and delicious. I would study until the university library closed at 11 pm, sustained by the packed lunches she sent me off with each morning. I let her assume most, if not all, of the cleaning, furnishing, and financial "chores”. She did all this in addition to holding down a physically and emotionally demanding job in the orthopaedics ward of the Montreal Children's Hospital.

We early on agreed to pool our incomes, though hers was significantly higher than mine. This arrangement made it possible for us to think realistically about me being able to do my last two years at Sir George full time. My debt to her was and remains incalculable. In return for her magnanimous generosity, I gave her a rather lonely existence. Fortunately she had a social life of sorts on the ward. Though we were both keen to become proficient skiers, I felt that I could not afford either the time or the money. So Frances had to go into a sort of social hibernation.

Without the Sir George commitment to evening students I could not have received a university education. The education itself was in no way inferior or unorthodox. As a general B.A. student, I did the standard introductory courses (the so-called "101's") for the first two years. At that point, I could either opt to "major" in a given subject, which involved a moderate degree of specialization, or apply for the more specialized and more rigorous Honours program.

I was accepted as an Honour’s student in History. My honours dissertation, a major research project, examined the origins of job reservation laws in South Africa, and how they came to be a major component of the Apartheid policy.

My interest in this topic began with my exposure to legalized racial discrimination in Bermuda. In my third and fourth years I continued, as far as possible, to specialize in African subjects, both past and present. My research interests ranged from the West African slave trade to the conquest of Nigeria, and included anti-colonial terrorism in Algeria and Kenya. I had first learned about the Mau Mau from some senior colleagues in Bermuda who had been seconded there.

As already mentioned, I used my practical experience of diving with Brian Malpas in Bermuda to land a lucrative job at Montreal's Expo 67. This "windfall" income encouraged me to quit my day job in order, at last, to have more time to study. Being no longer tied to 9 to 5 office hours, I was also able to accept an occasional modeling job.

My last student summer job, in 1968, was with the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce - washing the windows of the second highest ski-scraper in Montreal.

Not surprisingly, my grades improved once I no longer had to work full-time. So much so that my professors strongly encouraged me to apply for a coveted McConnell Fellowship at, of all places, McGill. If successful, I would be paid by the university to obtain my M.A. and Ph.D. - a generous stipend, all fees, plus travel expenses. I must confess to feeling vindicated and a little smug when informed that I was to be awarded this fellowship. By way of celebration we bought a well-used Volkswagen camper - and decided to start a family.

Family and Academic Career in Canada

I began my four year McConnell Fellowship at McGill in 1969. Life became less stressful because I had no financial worries, and I could spend more time with Frances. We explored the mountains of New Hampshire in our VW camper. Frances proved to be a fast and adventurous hiker.

My first year at McGill was spent doing the M.A. "course work" in African History. I spent my second year (1970-1971) at the Centre for West African Studies at the University of Birmingham in England. We bought a second-hand Ford Transit camper, and on our way to Birmingham we stopped off in Paris, Rome, Athens, Dubrovnik, Munich, Brussels and ... Dagenham.

It had been six years since I had responded to the Bermuda Police advert in the Daily Express, and I found that I had changed more than Dagenham had. No wonder I had the occasional unpleasant dream in which I would find myself back in the Dagenham of my youth - still stuck in the clerical job at Fords. I deeply resented being told that the British education system was far superior to its North American counterpart. One unaccomplished former Dagenham friend even suggested that my Canadian Honours degree was equivalent to British ‘A’ levels.

My family and friends took to my Canadian wife right away. What impressed them was her reaction to the loss of her wedding ring in the course of a trip from Dagenham to Liverpool and back.

We had packed most of our worldly goods in an old trunk and sent it by sea to Liverpool. It arrived there just as the dockers were preparing for what was expected to be a long strike. So we jumped into our camper and raced up to Liverpool to get the trunk before the port was closed down by the dockers' picket lines. We got the trunk before the strike began, but only just.

On our return to Dagenham, Frances noticed that her wedding ring was not on her finger. With something approaching horror, she remembered taking it off for some reason while we waited in a warehouse for our trunk. She had, she was convinced, put in on a coat that was on her lap. When she got out of the van, it had probably fallen onto the concrete warehouse floor where it would likely have been crushed by one or more of the heavy machines which constantly criss-crossed the area.

Even if it somehow survived this danger it would be easy for someone to spot it and pocket it when no one was watching. Though faced with a unanimous opinion that she should reconcile herself to this loss, my five feet in height and a very little bit pregnant wife quietly refused to just give up. She calmly announced that she would travel to Liverpool by train early the next morning and take a bus to the docks. And she would go alone, since I had an important interview in London that day.

When I returned to Dagenham in the late afternoon I ran into her at the Dagenham Tube station. She did not need to noisily declare her "mission accomplished." The I-told-you-so smile and the barely perceptible raising of the ring hand said it all with her usual understated eloquence. I later learned that she had arrived at the dock gates to find that the strike had begun but there was no picket line. The docks were nevertheless officially closed, and the policeman on duty could have turned her away. Instead he helped her find the warehouse, which, thanks to the strike, was now empty and unused. It took her just a few minutes to find the ring.

We celebrated at my "local" at Gallows Corner, where Frances surprised and amused the public bar "locals" by ordering a pint of Guinness, an appropriate pregnancy craving for a Canadian whose epic search for the lost ring delighted the pub's best customer – my Irish Uncle Pat.

Shortly after arriving in Birmingham in September 1970 our first son was born. Predictably, we named him Patrick after my Irish Uncle, but like my uncle he prefers to be called Pat. He is now an RCMP detective in Whistler, B.C. His arrival helped us to act on our doubts about the wisdom of me preparing to become a specialist in an area racked by ruinous wars, corruption, and dictatorship. The weak job prospects for Africanists convinced us that not to change course would be irresponsible, especially since the demand for historians in Canadian race relations looked more promising.

Back to McGill

We returned to Montreal in the Summer of 1971. We had both enjoyed our year in Birmingham. The reorientation of my academic career entailed some new and major preparations, the most onerous of which was a year of intensive reading and seminar presentations followed by a three hour Ph.D. Oral Comprehensive Examination. A panel of professors could test one’s knowledge and understanding of any subject you had covered at any point in your university career.

It is perhaps worth noting that British Ph.D. candidates (those working towards a doctoral degree) face no equivalent ordeal. The sole requirement for them is their thesis or dissertation. The silly British people who denigrate American universities might note that “top of the line” U.S. universities, such as the University of Wisconsin, require their doctoral students to do two years of course work, and both oral and written Comprehensives.

I survived my Oral Comps with the help of a bottle of Irish Whiskey which I had concealed in my briefcase! For my next challenge I needed a bottle of wine, but French wine only s’il vous plait. McGill requires Ph.D candidates to be able to translate from a “foreign” language related to their research field into English. Naturally, since I expected to settle in Montreal, I chose French, and set my sights on becoming fluent.

During my first few years in Montreal, I felt embarrassed evry time I said, "sorry I don't speak French," the language of about 80% of the population. What seemed to me to be odd was that the majority of the English speaking population were no more able to speak French than I was. But what was odder still was that, far from being embarrassed by this definicnecy, they regarded it as the birthright. In the rough game of empire building it was incumbent on the vanquished to learn the language of the victor. So the” Bloody Frenchmen” had to bloody well speak English – at least in Montreal and the industrial areas controlled for the most part by the English-speaking minority. Ironically, only when I returned to England to research and write mainly South African history did I make a serious effort to learn French. During my four years of undergraduate study I had to work such long hours that I had to put off learning French.

A la guerre!

I had taught myself the basics of the French language in the language lab at the university of Birmingham, which I visited for an hour every weekday. After about two months of this boring but necessary rote learning, I spent about a month with a French family and enrolled in an intensive French summer program in Boulogne. By the time I returned to Birmingham to prepare for our return to Montreal, I had actually begun to dream in French.

Anxious to practice and show off my new-found linguistic proficiency I, jumped into the French taxi which came to take me to the train station and ferry dock and in well-enunciated French said “a la guerre,” meaning “to the war” rather than “a la gare,” meaning “to the station.” A quick look at the reflection of the driver’s face in the mirror told me that I had made a humorous mistake, one that I quickly identified.

Communism: A Brief Flirtation

I wish that I could dismiss my very short-lived attraction to Marxist Communism as a youthful “mistake.” I did not make a mistake: I allowed myself to be literally misguided by radical professors, a number of whom were not scholars but apologists for murderous Communist dictators. These included Mao Zedong and Cambodia’s Pol Pot. It is hard for today’s students to imagine the cult-like fanaticism of the Maoists.

I found out the hard way. I was in my first year at McGill and busy trying to understand the origins of Apartheid in South Africa. So naturally, I gladly accepted an invitation from one of the former professors at Sir George to a lecture on that subject at McGill. The speaker knew nothing about South Africa – except that its racism was a tool of American imperialism and capitalism! Utter nonsense, I said politely, when questions were invited: the South African white minority created Apartheid.

A circle soon formed around me and insults and threats were hurled in my direction: I was a “Trotskyite pig” who used “gangster logic” instead of “people logic,” and so on. I recognized these as the hallmark of the Maoist “Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist),” known for its beating of more moderate campus activists. At this point, a group of Ethiopian women put themselves between me and the mob while slowly moving to an exit.

Finding an Academic Job

Our second child, Brian, now a manager with Quebec's Cirque de Soleil, was born in 1973, the year my McConnell Fellowship expired. Lady Luck saw to it that my need for a job coincided with the baby boomers reaching college age, and with Quebec's creation of a new junior college system. The penury of qualified lecturer’s best explains why I got an offer to teach economic history part-time at Montreal's Dawson College - despite never having studied the subject. I got the required text-book and kept a week ahead of the students. At the end of the semester I was offered a full-time position teaching Western Civilization, a "survey" of everything from "Plato to NATO" - since cleverly updated as "Adam to Saddam." A year later I got carte blanche to create what was to become my mostly lively and popular course. History of Terrorism...

Getting Comfortable at Dawson

At first I regarded my Dawson job as a convenient and not too demanding position suited to my commitment to finishing my doctorate and moving on to a university job, preferably at McGill. With just twelve hours of lecture time per week and three months’ vacation, I could not have asked for a better opportunity to realize this ambition while at the same time enjoying virtually total freedom to teach as I wished - certainly not the same as McGill, where I could expect to teach multiple sections of a Canadian survey course. With the average enrolment close to 200 and most grading being done by teaching assistants, McGill Profs had little chance to get to know their students. At Dawson, where class sizes rarely reached 40, faculty could get to know students well - sometimes too well, or so I am told.

As I gradually developed an appreciation of what Dawson had to offer, I came to feel that becoming an untenured, not particularly well-paid assistant professor at McGill might not after all be what I wanted. In 1976, before finishing my Ph.D. thesis, I began my McGill teaching career with a graduate course in North American Native History. The course, intended for high school history teachers, went so well that McGill and Dawson readily agreed to my idea of an informal and flexible joint appointment, one that would give me the freedom of Dawson and the greater intellectual challenge of McGill's advanced, lower enrolment courses. Both institutions were commendably flexible, even permitting me to take a year's leave from Dawson to teach full-time at McGill. I never regretted this arrangement. It made for a busy life, but one which l enjoyed immensely.

Ph.D. Thesis - False Start

In the meantime, on the research side of my career, my thesis advisor approved my proposal to write a history of a Christian community of literate bible-reading Inuit (Eskimos) founded by German missionaries in 1747 and operated until 1955. After six months of background research, I travelled to the Inuit village of Hopedale in northern Labrador on the summer supply steamer. A week after my arrival, a German anthropologist informed me that a Danish scholar had just submitted a book devoted to "my" German missionaries. I would have to find a new, original thesis subject. The next day a bush pilot gave me a "lift" in his float-plane to Goose Bay, where I could take a regular flight to Montreal.

Though disappointed, I felt that my first "field work" had given me a new appreciation of the skills and tough fatalism of the Inuit hunters and their long-suffering wives. I visited in July when the frigid, dark days of winter make way for the summer's long days and sodden tundra - ideal conditions for the countless millions of swarming mosquitoes and biting black flies. Foolishly dismissing as exaggerations the tales of insect depredation, I refused to daub myself with sticky repellent when I volunteered to help unload the supply ship. In the absence of trucks or cars, I grabbed a heavily laden wheel barrow, leaving me with no hands to defend myself. The Inuit hunters and fishermen pretended not to notice my predicament, and I refrained from seeking help for fear that they might offer me some of the rancid bear fat, said to keep the bugs at bay - along with everyone not raised in a traditional Inuit home.

The problems the Inuit encounter when they exchange a nomad ice life where the only law is an "eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth" for permanent settlement are severe and intractable. Resort to alcohol, drugs, and suicide is widespread. The policing of Inuit communities is often a nightmare, and the RCMP pioneers who took up this challenge should be national heroes.

My short and apparently dead-end initial encounter with Inuit became something of a turning point for me. I decided to cut my losses and abandon the idea of making the Inuit the research component of my Ph.D. I did, however, accept an invitation to a conference in Copenhagen devoted to exploring the differentapproaches to Inuit studies. I felt a little guilty when I received a grant which paid not only for all my travel expenses but for a "stop-over" in London, where I had a week-end visiting family and friends in Dagenham.

I returned to Montreal keen to put the Inuit fiasco out of my mind so that I could get on with preparing my second Ph.D. thesis proposal. Instead, the Education Ministry found an Inuit problem at Dawson and the college asked me to fix it. Ministry officials discovered that none of the twenty or so Inuit students brought down to Dawson each year during the previous ten years at great expense to the college had graduated. The Ministry officials began to ask awkward questions about the dismal performance of these Inuit students at Dawson.

I was given two years to discover the reasons for this extraordinary situation as well as to devise and test a remedial program.

I applied for and was given what amounted to a two-year consulting contract. The first year would see me spending quite a bit of time visiting the homes and schools of young people who had studied and failed at Dawson. It did not take long to confirm with first-hand evidence my early feeling that, to put it bluntly, most Inuit students would prefer to party than to study. Devoting a lot of time to study or homework, I was told, is not "our culture”.

An ethic of non-interference served to reduce conflict in societies which, like the Inuit, had neither law nor government. But it is a serious handicap for anyone wishing to "get on" in our world, since it keeps parents from making children do their homework or get up in time to go to school.

I do not agree with the “Politically Correct,” “Affirmative Action” approach to the very real and troubling inequality between what Quebecers refer to as “visible minorities” and the white majority. I am convinced that the Inuit fiasco at Dawson was caused by a de facto, unacknowledged and, above all, unexamined lowering of standards in order to achieve greater equality. But far from improving the economic or social status of the Inuit, this educational favouritism has exposed the woefully ill-prepared students who come down to Montreal to almost certain failure.

They have been set up to fail – not deliberately, but rather, at least at first, as a result of the doctrinaire commitment to a bankrupt policy. Later on, teachers and administrators tend to become cynical and hypocritical as they discover that they have a vested interest in the “progressive,” PC orthodoxy. Life is less stressful if you don’t give homework or “hard” English readings.

I developed a curriculum designed to provide the basic academic survival skills, which should have been imparted by the high schools. We found that the Inuit college students had an average reading level of grade 5. The experimental year-long catch-up program was a total failure, despite me recruiting dedicated faculty and support staff.

And Now for Something Completely Different

Ever since reading some of the transcripts of the Nuremberg Trials while still in high school, I developed an interest in and sympathy for Israel. Later on I used the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a case study in my History of Terrorism course.

Dawson had a Summer Work-Study Program at Kibbutz Dir. in the Negev Desert. When the Jewish History lecturer needed a summer off, I impulsively offered to give myself a crash course in the subject if I was allowed to replace him. As it turned out, I would spend the next two summers at Dir. By day I toiled in the scorching fields and sweltering chicken houses; by night I gave lectures on Jewish History to Jewish college students from Dawson and other Montreal colleges... The students tended to be “work shy” and not too keen on getting up at 5 a.m., especially after a night of partying. So the kibbutz leaders expected me to be play the role of “sergeant major”! Apparently I did not disappoint them, hence their invitation to me either to make “ALIAH” – emigrating to become a kibbutz member (no circumcision required) or, at the very least, to come back the following summer – which I did. I was expected to attend night classes in Hebrew, but I was usually too tired to learn much.

I did excel at one after- dark activity: chicken chasing. Kibbutz Dir had about 40,000 chickens, all of which had to be slaughtered because they had become infected by a nasty virus. I was asked to participate in the carnage, not, fortunately, as an executioner, but on the catching side of things. Chickens, notoriously agile and fast, have to be hunted down at night. Catching them in daylight hours is impossible; catching them in the dark was truly hazardous.

The Montreal students, alerted by some of the kibbutz teenagers, refused, en bloc, to follow their intrepid leader into the huge, ugly, and smelly breech. I confess to being relieved to learn that I was not expected to catch chickens. Rather, my job would be to follow one of the veteran catchers into the darkness and when he shouted “AR bah”, four in Hebrew, I had to grab two chickens from each hand and carry them upside down by the feet to a man who would load them into a truck.

The best catchers tended to be small, wiry types with lots of stamina and nerve. They had small dimmed flashlights which they turned on often enough to avoid colliding with the concrete pillars which supported the chicken house roof, but not so often as to allow the chicken you were chasing to have enough light to use a kind of slalom technique to navigate its way to the safety of the dark corners. I will never forget the meaning of “AR bah,” which became my nickname around the kibbutz.

I got on extraordinary well with the older kibbutz members, especially the Hungarians. Survivors of the Holocaust, they had founded Dir along strict socialist lines after surviving the Holocaust. I found their Marx-inspired attempt to abolish the family misguided. They believed that families did not distribute power equally and, more importantly, they perpetuated inequality by nepotism and inheritance laws, So the rules of the kibbutz required members to place their babies fairly soon after birth in a Children’s House, where they remained until they left to do their military service. I discretely avoided any mention of this policy.

In general, I came to admire their work ethic, their respect for learning, and their sincere commitment to a peaceful and fair settlement of the Palestinian question. Relations with the Bedouin Arabs who lived nearby were so good that Bedouin with AK 47`s guarded the kibbutz at night.

A few of our students not only made it clear that they not only did not like Arabs, but they openly approved of terrorist attacks on them by radical Zionists. After some hesitation, I decided to consult the kibbutz leaders rather than intervening in this matter myself. They offered to invite all of the Montreal students to an informal meeting which I would chair. It was interesting to witness the veteran kibbutznics, most of whom had fought in wars against Arabs, trying to moderate the views of my group’s extremist fringe.

My long-standing interest in the terrorism practiced by both sides in the Arab-Israeli conflict prompted me to use my occasional week-end off to get a better “feel” for the conflict’s context. To better understand the plight of the Palestinian refugees was my principal aim. So I traveled around the West Bank on the rusty, noisy, old “Arab buses” rarely used by Israelis or tourists, who preferred to take the luxurious and clean Israeli buses. I rather liked the novel intimacy of squawking chickens, crying children, and seats occupied by huge baskets of farm produce which the mostly female passengers were taking to sell in the towns.

Wearing a “Panama” straw hat and carrying a prominently displayed British Airways shoulder bag – complete with Union Jack – was probably unnecessary but I sought to reduce my chances of being taken for anything but a British tourist.

I got off the bus in Hebron, the West Bank’s biggest town and the scene of much of the area’s terrorist activity, Palestinian and Israeli. It is like a political and religious fault-line, with much of the tension being generated by the desire of both Jews and Moslems to control Hebron’s tomb of Abraham, who is regarded as sort of Founding Father by both religions.

The Hebron settlers, mostly affluent, well-educated Americans, incubated a racist, genocidal Zionism whose terrorism received a much higher degree of public and official support and even hero worship than I would have expected. A fairly short time after my reconnoitering in Hebron, a young Jewish “settler,” a medical doctor from New York, had walked into the tomb with two or three assault rifles while the Moslems were at prayer and killed 28 of the praying Moslems.

I had an interesting and encouraging encounter with a Palestinian on my second week-end off. I rented a little Fiat and headed for the Gaza Strip, the world’s only perennial refugee camp. The Strip was the only part of “British Palestine” which Israel could not manage to hold on to during the 1948 War of Independence. Egypt grabbed it as it was filling up with frightened Palestinians, some of whom had been expelled from their homes, while others had fled after hearing stories about Israeli attacks on civilians. Some of these tales were true, but most seem to have been concocted and spread by the Israelis.

The Gaza refugees expected to go home when the combined armies of their Arab neighbours defeated the nascent Jewish state. That did not happen. Instead, in 1967 Israel’s soldiers swept the Egyptians out of Gaza and found themselves with an exploding population and a permanent refugee problem. It was the home of Palestinian terrorism, and I felt apprehensive as I headed for Gaza City in my little rented car with big Israeli license plates.

Just that morning I had noticed that my rented car had the standard Israeli license plates. There was no way to protect myself - could not roll up the widows because the car was not air conditioned. But I could give a lift to one of the many Palestinians trudging home to their refugee camps after a long day spent providing Israel with cheap, tractable labour.

I stopped beside an older man wearing the traditional Kamiah head-dress. His pace quickened slightly by way of acknowledging me, then he joined me and we drove into the center of Gaza city, where he made it clear that he wished to get out. By using signs he insisted that I stay put until he returned. About five long minutes later he came out of a shop with a cold bottle of coke for me!

EDITOR’S NOTE - David had been in the process of writing his reminiscences in short segments for several years after our expobermuda website was first created, and he would send me additions to it from time to time for editing.

In January 2013 he wrote his own personal account of the BELCO Riot of 2nd February 1965 during which he had been injured, and which may have been a contributory cause of his Parkinson’s Disease. Nevertheless, he wrote a concise and factual account of the riot which we published and which can be viewed at http://expobermuda.com/index.php/articles/178-belcoriotmulhall

His article was also published by the Royal Gazette on 2nd February 2013 on the 48th anniversary of the BELCO riot. This article can be viewed at

http://www.royalgazette.com/article/20130202/NEWS/702029983

David’s account of the riot was viewed in some quarters as controversial, and numerous comments were posted under the article, including one which perhaps best summarizes why David’s account was sorely needed in order to balance the historic record of the events of that fateful day. This comment is reprinted below.

Later in 2013 David’s condition seriously deteriorated and it became infinitely more difficult for him to sit and type on his computer. He would often send emails with “updates” but these, at times, were almost incomprehensible. Even so, I had great hopes that he would be able to finish his memoirs. Sadly this was not to be the case. He died in July 2013.

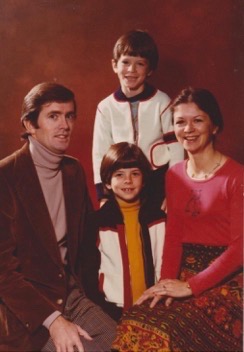

Postscript by Frances, Patrick, and Brian Mulhall (David’s wife and their two children)

David completed his working career at Dawson College, teaching an eclectic mix of history courses, the most popular continuing to be his Terrorism Course. One of his most cherished accomplishments was co-founding a Liberal Arts Program in 1982 with his good friend and colleague, Aaron Kristalka. This program has been hugely successful and remains on-going at Dawson.

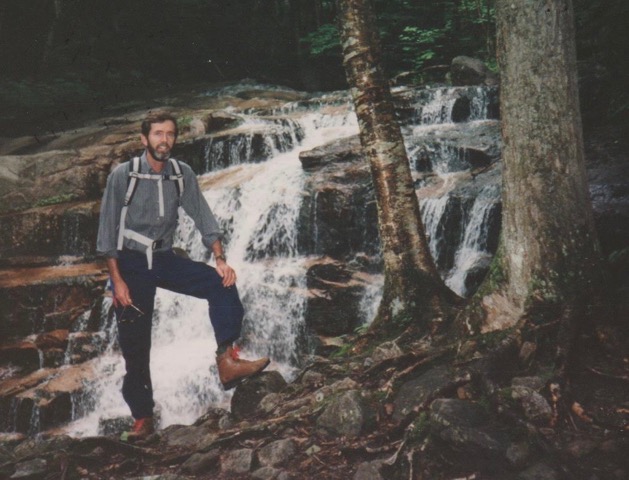

David was an avid skier, both downhill and cross-country. He successfully completed the 2 day, 100 mile Canadian Ski Marathon in 1981, earning the Jack Rabbit Coureur de Bois medal.

Summers were spent relaxing at the family cottage on Lake Lovering in the Eastern Townships (Quebec) where David enjoyed snorkelling, windsurfing and sailing. Travel over the years included trips to Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Spain, Ireland, Hawaii and Alaska.

In 1998, during the “Ice Storm of the Century” David was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. The disease took it’s toll, and in 2001, he reluctantly went on sick leave, followed by retirement a few years later.

In 2006 the decision was made to move to Peachland, British Columbia, to enjoy a milder climate.

After seven happy years, David tragically died while snorkelling in Okanagan Lake in July 2013, only days after two wonderful weeks spent with his two sons, daughters-in-law, and four grandsons.

We would like to extend a special thanks to his colleagues and friends during his time spent with the Bermuda Police Department. Those experiences were very special to him, and often recounted to friends and family. The enduring friendships and hospitality shown during visits decades later meant a great deal to him and our family.

EDITORS NOTE - We are indebted to David’s wife, Frances, and their two sons, Patrick and Brian, for their assistance in writing the above conclusion, giving permission for us to publish David’s memoirs, and also for kindly providing the photos used to illustrate it.

The following comment was posted in the Royal Gazette under the article written by David and published on 2nd February 2013 - the 48th anniversary of the BELCO riot:-

“When describing historic events there will always be variations of the truth. As Laverne Furbert points out, there are several accounts of the BELCO Riot as written by Ira Philip and Ottiwell Simmons. I have the very highest regard for both men. Ira has been writing about the history of black people in Bermuda for as long as I can remember, and from a time when almost no-one else did so.

Ottiwell Simmons led the BIU through the some of the most difficult years in our history, particularly during segregation and the early years of unionization in Bermuda. However, I would venture to say that chances are Mr. Philip was not present at the BELCO Riot, and I seriously doubt if he or Mr. Simmons, or anyone from the BIU ever interviewed even one of the police officers who were there that morning, 17 of whom were injured including one who had his skull caved in and never recovered.

I was present outside BELCO on that fateful morning watching the situation unfold before the rioting got underway, and fortunately for me, I was called away to attend court on another matter. The police officers who remained there were totally outnumbered and were there for one purpose only, and that was to try to maintain some semblance of order on the picket line with instructions to make sure that any BELCO employees wishing to cross the picket line could do so peacefully.

Those police officers were armed with nothing more than their regular batons and handcuffs - nothing more. They certainly did not have a cache of iron bars or weapons of any sort hidden behind the BELCO wall, or anywhere else.

David Mulhall has written his own account of the events of that morning without being solicited by anyone. He is in the process of writing his memoirs for later publication on our Bermuda Ex-Police Officers Association website (expobermuda.com). After leaving Bermuda, David obtained his PHD and went on to become a university history lecturer in Canada. His studies included African history. He has no axe to grind against either the Police Force or the BIU. In fact he made no bones about the fact that while in Bermuda he was very sympathetic towards the efforts of the BIU in striving to bring social justice to Bermuda; a view shared by others of us in the Police Force.

Contrary to Ms. Furbert’s assertion, David Mulhall is not attempting to rewrite history. But he was present outside BELCO on the morning of 2nd February 1965 when history was being made, and he is fully entitled to describe that history as he saw it and felt it that morning. No-one has a monopoly on the truth, but I believe David Mulhall’s account sets the record straight from the point of view of the 17 police officers who were injured that morning. I can think of no-one better qualified to write a first-hand account of the BELCO Riot than a man who has devoted his life to studying and teaching history.